More than 300,000 UK children were estimated to be unhappy with their lives before the pandemic, according to research warning of a “deeply distressing” downward trend in wellbeing.

The decline of British happiness

The tenth annual review from The Children’s Society found 6.7% of children aged 10 to 15 were not happy with their lives overall in 2018-19 – up from 3.8% in 2009-10. The charity analysed data collected as part of the Office for National Statistics’ Understanding Society survey for its Good Childhood Report.

Extrapolating this to population level, this suggests 306,000 children are unhappy – up from an estimated 173,000 children a decade ago. Worries about school and appearance were key factors thought to be behind the decline in happiness, the report found.

4% of children aged 10 to 17 were found not to be coping with the pandemic and to have low wellbeing, according to the society’s own survey of more than 2,000 young people between April and June in the UK. The research found those who were unhappy with their lives aged 14 were much more likely to develop symptoms of mental health conditions, including self-harm, within the next three years.

This is based on analysis of the Millennium Cohort Study, which follows the lives of 18,000 people born across the UK in 2000-02.

Measure wellbeing like we measure the economy

The charity says the government must start measuring the wellbeing of children, as well as adults, and produce an action plan to tackle the causes of low wellbeing.

Writers Amit Kapoor and Bibek Debroy have previously argued:

Economic growth has raised living standards around the world. However, modern economies have lost sight of the fact that the standard metric of economic growth, gross domestic product (GDP), merely measures the size of a nation’s economy and doesn’t reflect a nation’s welfare. Yet policymakers and economists often treat GDP, or GDP per capita in some cases, as an all-encompassing unit to signify a nation’s development, combining its economic prosperity and societal well-being. As a result, policies that result in economic growth are seen to be beneficial for society.

We know now that the story is not so simple – that focusing exclusively on GDP and economic gain to measure development ignores the negative effects of economic growth on society, such as climate change and income inequality. It’s time to acknowledge the limitations of GDP and expand our measure development so that it takes into account a society’s quality of life.

According to the analysis of the Understanding Society data, more boys are becoming unhappy with the way they look, with the proportion rising from 7.8% to 13.0% over the past decade. The proportion of girls unhappy with their appearance remained at a similar level (15.7% up from 14.9% ten years ago). One in eight (11.9%) children are now unhappy with their school lives, up from 8.9% a decade ago.

Mark Russell, the Children’s Society chief executive, said these “worrying trends” must not be allowed to worsen. He added:

It’s deeply distressing to see that children’s wellbeing is on a 10-year downward trend and on top of this a number of young people have not coped well with the pandemic.

Children’s happiness with their lives has the potential to have far reaching consequences, and has been linked to their attainment and mental health as well as their safety and hopes for the future. It’s vital we protect children in early adolescence, as our report has shown their unhappiness at this stage can be a warning sign of potential issues in later teenage years.

It’s so important we listen and help children in this crucial stage of their development, providing early well-being and mental health support whenever they need it.

More support needed

A Conservative government spokesperson said:

We know the past year has been incredibly difficult and so we are prioritising the wellbeing of children and young people, backed by more than £17 million to build on the mental health support currently available in schools, including our wellbeing for education recovery and return programmes to support students experiencing trauma, anxiety, or grief.

We are also investing £3 billion to boost learning, including £950 million in additional funding for schools which they can use to support pupils’ mental health and wellbeing and our expanded holiday activities and food programme can also be beneficial for children and young people’s physical and mental wellbeing.

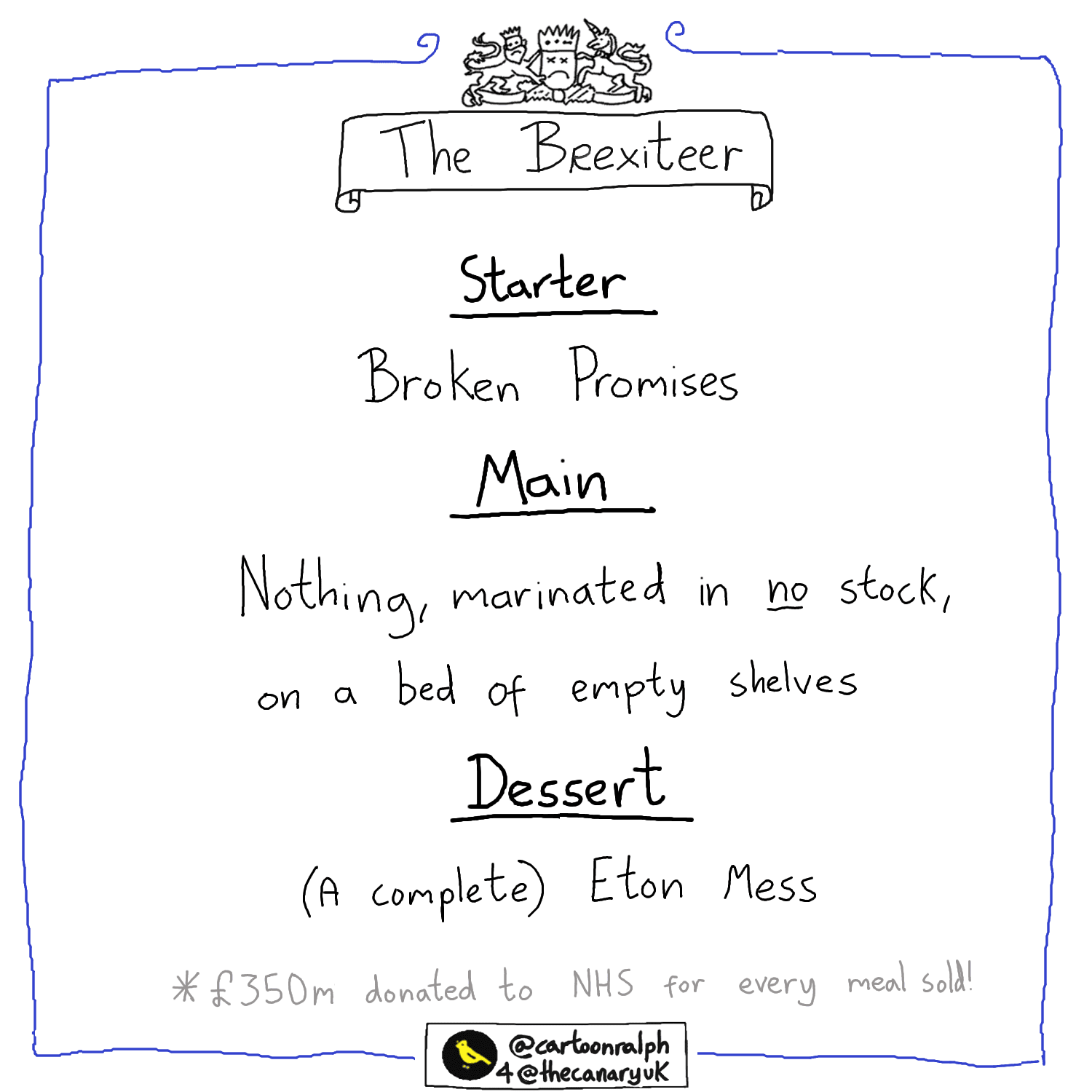

Various Conservative governments have been in power for almost all of the period researched in which children’s wellbeing diminished.

Tom Madders, director of campaigns at YoungMinds, urged the government to invest in a national network of early support hubs so that young people can get mental health and wellbeing support as soon as they start struggling.

He said:

The last year has been incredibly difficult for lots of young people with many struggling to cope with social isolation, loneliness and worries about the future.

It’s clear that the pandemic is just one part of the picture however, with young people facing multiple pressures that are impacting their overall wellbeing.

Peter Wanless, chief executive of the NSPCC, said:

We need to see more mental health support for young people in both the classroom and the community, together with early intervention services that can step in to support children and families before problems escalate to crisis point.