England’s chief medical officer Professor Chris Whitty has said that the new variant of coronavirus (Covid-19) can spread more rapidly. But he also stressed there was currently no evidence that the new strain causes higher mortality rates or that it affected vaccines and treatments.

Here the PA news agency answers some of the key questions about the variant:

– Is this something unusual?

There have been many mutations in the virus since it emerged in 2019. This is to be expected – SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus and these viruses mutate and change.

Public Health England (PHE) said that, as of 13 December, 1,108 cases with this new variant had been identified, predominantly in the South and East of England.

It has been named VUI-202012/01, the first variant under investigation in December.

– What has Whitty said?

Whitty said the UK has informed the World Health Organisation that the new variant coronavirus can spread more rapidly.

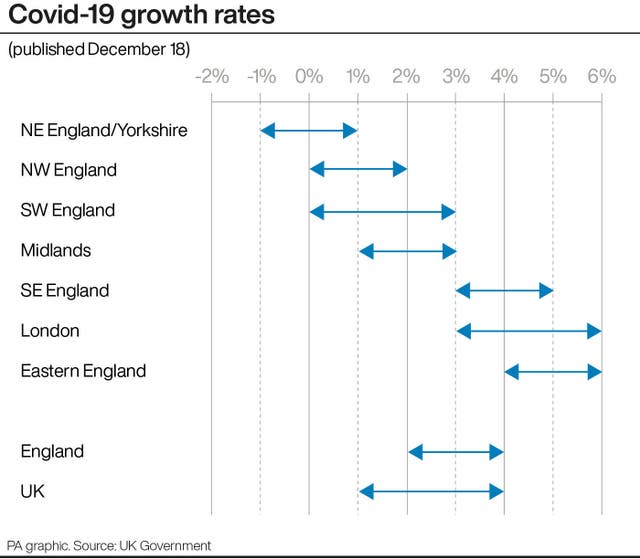

In a statement on 19 December, he said that the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG) now consider that the new strain can spread more quickly. This is following the rapid spread of the new variant, preliminary modelling data, and rapidly rising incidence rates in the South East.

– Is this something to worry about?

If the virus spreads faster, it will be harder to control. However, there have already been various strains of coronavirus with no real consequence.

The Covid-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium said it’s difficult to predict whether any given mutation is important when it first emerges. And that it would take “considerable time and effort to test the effect of many thousands of combinations of mutations”.

It said any changes that lead to an increase in reinfections or vaccine failure are of greatest concern. And most attention is on mutations in the gene that encodes the spike protein.

There are currently about 4,000 mutations in the spike protein gene.

Whitty has said that there’s no current evidence to suggest the new strain causes a higher mortality rate or that it affects vaccines and treatments. But he said that “urgent work” was underway to confirm this. He also warned that it was “more vital than ever” that people continued to take action to reduce the spread of the virus.

– Is it the first novel strain detected in the UK?

A number of variants have been detected using sequencing studies in the UK.

A specific variant (the D614G variant) has previously been detected in western Europe and North America, which is believed to spread more easily but not cause greater illness.

But it’s thought this is the first strain that will be investigated in such detail by PHE.

– Are new variants always a bad thing?

Not necessarily. They could even be less virulent.

However, if they spread more easily but cause the same disease severity, more people will end up becoming ill in a shorter period of time.

– Should we expect the virus to become more harmful?

Not really. Only the changes that make viruses better for transmission are likely to be stable and result in new circulating strains.

The pressure on the virus to evolve is increased by the fact that so many millions of people have now been infected.

Most of the mutations won’t be significant or give cause for concern. But some may give the virus an evolutionary advantage which may lead to higher transmission or mean it’s more harmful.

– Will vaccines still work?

PHE said this new variant includes a mutation in the spike protein. And that changes in this part of the spike protein may result in the virus becoming more infectious and spreading more easily between people.

However, health secretary Matt Hancock said the latest clinical advice is that it’s highly unlikely that this mutation would fail to respond to a vaccine.

The vaccine produces antibodies against many regions in the spike protein, and it’s unlikely a single change would make the vaccine less effective.

However, this could happen over time as more mutations occur, as is the case every year with flu.

– So what are the scientists doing now?

Scientists will be growing the new strain in the lab to see how it responds. This includes looking at whether it produces the same antibody response, how it reacts to the vaccine, and modelling the new strain. It could take up to two weeks for this process to be complete.

COG-UK is carrying out random sequencing of positive samples across the UK to compile a sequencing coverage report. This is sent to each of the four public health agencies each week.

It said random sampling is important to capture regional coverage.

– If it’s not that big a deal, why do we care?

While other variants have been identified in the past, it appears this particular strain is spreading quite fast. Meaning it could be more transmissible, and therefore warrants further investigation.

Professor Mark Walport, a member of the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), said there was a possibility that the new strain could have a “transmission advantage”.

– What examples are there of other virus strains?

The Danish government culled millions of mink after hundreds of coronavirus cases in the country were associated with SARS-CoV-2 variants associated with farmed mink. This included 12 cases with a unique variant, reported on 5 November.

In October, a study suggested that a coronavirus variant that originated in Spanish farmworkers spread rapidly throughout Europe and accounted for most UK cases.

The variant, called 20A.EU1, is known to have spread from farmworkers to local populations in Spain in June and July. People then returning from holiday in Spain most likely played a key role in spreading the strain across Europe.