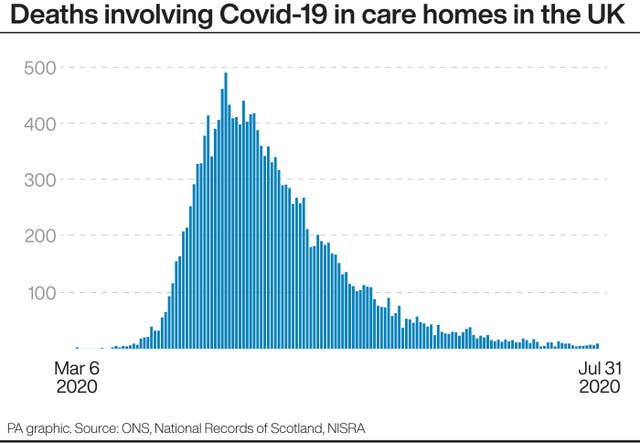

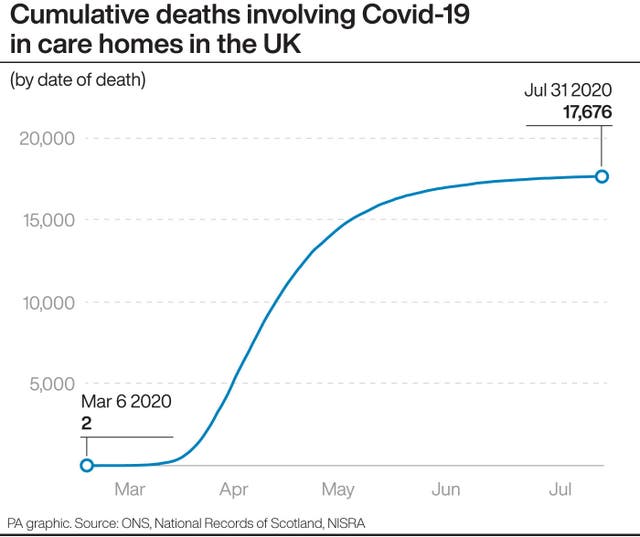

More than 400 deaths involving coronavirus (Covid-19) occurred each day in UK care homes at the height of the coronavirus outbreak, new analysis shows. There were more than 3,000 care home deaths involving coronavirus in one week in mid-April, according to the first UK-wide review of daily deaths by the PA news agency.

Huge significance

Deaths rose five-fold between the start of the month and the care home peak on April 17, when nearly 500 residents died. At this time, testing for all staff and residents – regardless of symptoms – was not available in England, Scotland, Wales, and the North of Ireland, while providers had not yet been advised to restrict staff movements between homes.

Carl Heneghan, professor of evidence-based medicine at the University of Oxford, believes staff movement was of “huge” significance in aiding infection spread in the absence of effective testing.

Thousands of hospital patients were discharged into care homes from mid March, and there were struggles to access personal protective equipment (PPE). PA analysed data from the UK’s statistics agencies to reveal the day-by-day death toll up to the end of July.

It comes ahead of 6 September – six months since the first care home resident death involving coronavirus – and also found:

– More than 400 deaths involving coronavirus took place in UK care homes on 11 days in April.

– Deaths increased more than five-fold in just over two weeks, from 93 on 1 April to 490 on 17 April – the highest daily total.

– By 26 April, when the first UK nation announced that providers should restrict staff movements, 9,074 care home deaths had occurred across the UK – 51% of the total up to 31 July.

– By 28 April, when the first UK nation announced testing for all care home staff, regardless of symptoms, 9,776 care home deaths had occurred across the UK – 55% of the total up to 31 July.

England’s chief medical officer Chris Whitty said in July “major risks” in social care settings were not considered early on, including staff working in multiple residences and those not paid sick leave.

Lacking experience and absent leadership

Asymptomatic testing was first announced in England on 28 April, despite Public Health England (PHE) saying it was a concern from the end of March. The first nation to advise care home providers to restrict staff movements between homes was Northern Ireland, on 26 April.

There was a gap of around two months between guidance from PHE advising care homes to share workforces in mid-March to fresh advice to restrict staff movement announced on 13 May alongside funding to control infection spread in care homes in England. Prof Heneghan said this was due to a lack of clinical experience in the government’s advisory team and an absence of leadership.

Acknowledging care homes faced high levels of staff off-sick or self-isolating, he told PA:

The Government should have advised that agency staff, if used, should be employed in a single care home and not travel between multiple care homes. That advice should have been given in the middle of March.

This should have been accompanied by funding to increase staffing levels, he added. He believes this should be applied going into winter, but has seen no “sense of urgency” about protecting care homes.

Care England chief executive professor Martin Green said guidance has been “slow to come to fruition” and addressing this, particularly with regards to visits, is a matter of urgency.

He said:

Many care homes locked down before national guidance came into force. Unfortunately patients were discharged from hospital without testing and this, compacted with insufficient PPE, created huge challenges for care homes.

Routine testing is absolutely essential in order to establish confidence in the system for residents, staff, relatives and beyond.

Risks

The potential risks of staff movement were first discussed at a meeting of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) on April 21. Dr Ian Hall co-authored the paper discussed, which was not made public until 19 June. The University of Manchester academic told PA concerns around staff movement should have been made public as soon as possible and that, given capacity issues, he believes staff should have been prioritised for testing over symptomatic residents.

But he said:

What we weren’t aware of at the time back in April and May was the complexity of the staffing situation, and so one of the concerns was, I know, ‘if we go too hard on the potential for staff being a vehicle for transmission, then a lot of staff might be absent and that might affect the care needs of the otherwise healthy but vulnerable residents’.

So it’s a very delicate balancing act between trying to limit infection introduction and ensuring care is still provided.

Lessons must be learned

MHA, a UK care home provider, said mistakes must not be repeated and called for more funding, regular tests, and “no slip ups or delays”.

Chief executive Sam Monaghan said:

What this analysis does is confirm that during the peak of the virus the sector, despite following all of the best infection control measures, were not supported with what turned out to be the additional critical tools we needed to manage the spread of the virus.

Unison senior national officer Gavin Edwards said social care must be treated as an “essential public service” with pay and workforce conditions prioritised, to avoid a repeat of the first wave.

He said:

Social care workers are often paid poverty wages, employed on zero hours contracts and given no sick pay. In addition, many have faced a massive drop in income if they follow guidance and self-isolate. This clearly helped to drive infection rates in the sector.

A Department for Health and Social Care spokesperson said:

We have been doing everything we can to ensure care home residents and staff are protected, including testing all residents and staff, provided 200 million items of PPE, ring-fenced £600m to prevent infections in care homes and made a further £3.7 billion available to councils to address pressures caused by the pandemic – including in adult social care.

As a result of actions taken, almost 60% of England’s care homes have had no outbreak at all and the proportion of coronavirus deaths in care homes is lower in England than many other European countries.

In June, the Guardian reported:

The proportion of residents dying in UK homes was a third higher than in Ireland and Italy, about double that in France and Sweden, and 13 times higher than Germany.

It also stated that:

About 3,500 people died in care homes in Germany compared with more than 16,000 in the UK, despite Germany having a care home population twice as large. Its test-and-trace system and 14-day quarantine for people leaving hospital have been credited with protecting homes from outbreaks.