After 25 years of local and national protests, Campsfield House Immigration Removal Centre (IRC) in Kidlington, Oxfordshire, finally closed its doors in December 2018.

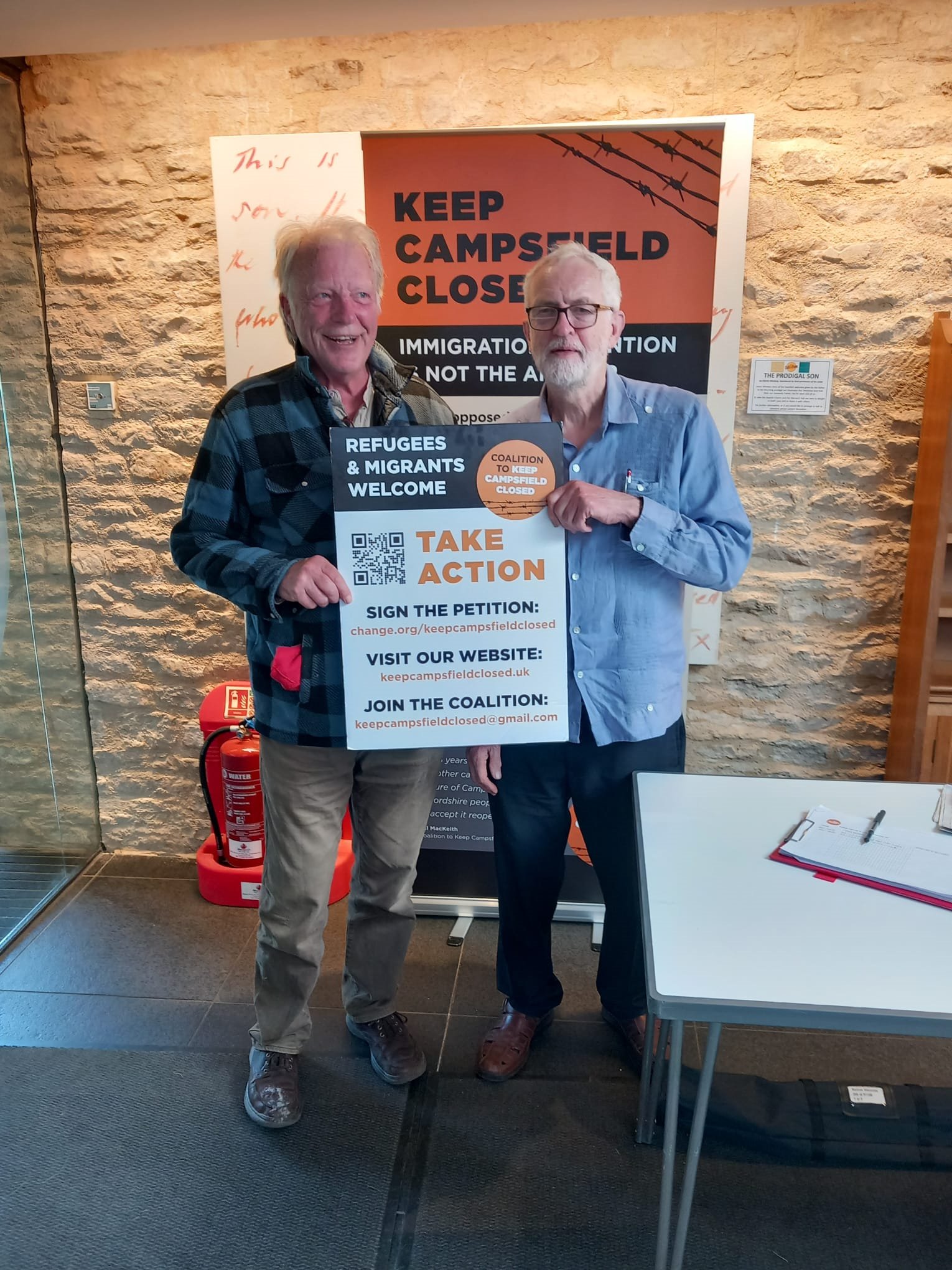

Opposition to it had been strong, and from the day the detention centre opened in 1993, a monthly demo took place outside its main gates, attracting all types of people, including Jeremy Corbyn and Anneliese Dodds.

Run for the Home Office by a private company called Mitie, Campsfield was mired in controversy and its closure was a huge victory not only for campaigners, but also for human rights.

Its closure was hastened by the publication of a report into the welfare in detention of vulnerable persons, known as the Shaw Review, which not only exposed the inhumane treatment taking place in the UK’s immigration system, but also found that detention in itself was harmful.

The review recommended that immigration detention should be used as a last resort, and the government promised to reduce the number of people held in these centres by up to 40% from 2015 numbers.

Campsfield House: first the Tories, then Labour make plans to re-open it

So campaigners, who had spent years fighting alongside Campsfield detainees and witnessed the human cost of the place, were understandably heartbroken when Boris Johnson announced plans, less than four years later, to reopen the immigration detention centre.

At the time, Campsfield House was very much linked to the Rwanda scheme, so when Labour took office and dropped the scheme, it was hoped the plans to reopen Campsfield would be scrapped. But instead, in August last year, Home Secretary Yvette Cooper, announced Labour was not only pressing ahead with reopening the centre, but also had plans to expand it.

In response to this shocking news, the campaign group Oxford Against Immigration Detention, and Asylum Welcome, also based in Oxford, got together and founded the Coalition to Keep Campsfield Closed:

Asylum Welcome’s Emma Jones said:

We are trying, through a variety of means – Freedom of Information requests and Parliamentary questions, to find out more, because we are very conscious that they’ve gone very quiet. News isn’t being shared, despite the fact that initially they said there’d be public consultations.

No planning permission has been submitted- as far as we can see, despite the fact that its been said they’d need it for phase 1 (to refurbish and reopen Campsfield) and phase 2 (to expand its capacity to around 400), but a contract has been awarded to Galliford Try, and work is in progress at the site, so we suspect they’ve found a way to get around the planning.

Although Galliford Try’s website says it “makes a real difference to people’s lives”, this is obviously not in a positive way, as a large part of the company’s money comes from construction in the custodial and defence sector.

In addition to the £70m contract to carry out both refurbishment and new-build at the Campsfield site, its other contracts include refurbishing Haslar Immigration Removal Centre (IRC) near Portsmouth, which closed in 2015 after reports of mistreatment and inhumane conditions, but is now set to reopen and expand. Galliford Try has also been awarded a contract to expand RAF Wyton – a top-secret base that plays a critical role in intelligence gathering for UK armed forces on global operations.

Immigration detention centres: a hotbed of harm and abuse

The Home Office held almost 19,000 people in immigration detention centres across the UK in the year to March 2024, many of whom had experienced torture, oppression, and trauma, and are extremely vulnerable.

Research has shown asylum seekers and refugees are at particular risk of mental health problems, compared to the general population, and this is not only linked to their pre-migration experiences, but also those during and post-detention.

Those who are already experiencing problems with their mental health are likely to see a significant deterioration as a result of being detained, but the necessary care provisions in these detention facilities are much less readily available than in the general community.

For those who have risked everything hoping to find safety and security in our country, their loss of liberty and the threat of forced return to their country of origin make immigration detention a particularly harrowing experience.

There is no automatic judicial oversight on decisions to detain, while a lack of knowledge about release dates causes huge amounts of depression and anxiety, because of the inability to think of any kind of future.

Britain is one of only a handful of countries, and the only one in Europe, to have no upper limit on the time a person can be detained. Research has found all detention to be inherently harmful to people’s physical and mental health, but indefinite detention to be even more so, and these problems are compounded if detainees are threatened with deportation at the same time.

The ‘ideological infrastructure’ that decides people are ‘illegal’

Centres like Campsfield House operate with a lack of safeguards and accountability, and detainees do not have an automatic entitlement to legal advice or allocation of legal representation.

It is extremely difficult for these people to access their rights, especially if they are being moved around the detention system, so when Campsfield was open, Asylum Welcome helped detainees access badly needed legal and medical support.

Jones explained that:

There’s a mental health crisis inside detention centres, and self-harm is happening on a daily basis. It’s not remotely surprising really, given that people are detained indefinitely- which is such a shocking abuse in itself. But indefinite detention is permitted in this country, for people who have committed no criminal offence but are just there because of their lack of papers.

If you don’t have status, meaning your immigration status is not resolved, you are liable to detention at any point in the process, which is very scary and open to all sorts of abuses. And that’s how something like the Windrush Scandal was able to happen…

The physical infrastructure of places like Campsfield, and also the ideological infrastructure, which says some humans are illegal, or these people are immigration ‘offenders’, leads people to believe some offence has been committed rather than an irregularity in someone’s status, or the fact that someone is going through the process of seeking asylum.

These places are synonymous with cruelty and, over the years, protests and disturbances were not only limited to outside the gates of Campsfield House. Detainees took part in rooftop protests and hunger strikes, demanding better treatment and trying to draw attention to the inhumane conditions and treatment inside the centre. Tragically, there were also two suicides.

Many of us are left wondering why immigration detention centres are allowed to continue causing so much misery and harm, indefinitely and for administrative purposes when, in response to the Shaw Review, the government at the time agreed detention should be reduced.

These centres are also extremely expensive to run, with almost £145 of tax-payer money spent daily on detaining each person, and annual costs of running these facilities rising each year, to more than £117m in 2024.

Immigration detention is little more than ‘performative cruelty’

Serious questions are also raised, as to the justification of immigrant detention, as statistics over the last decade show there has been a long-term fall in the numbers of people leaving immigration detention to be returned to their country of nationality or habitual residence.

According to government figures, in the year ending June 2023, of the more than 20,500 individuals who left immigration detention, 75% were granted bail and therefore re-entered the community. This highlights the fact that many people are unnecessarily enduring the distress of being detained.

Jones said that:

Often people are released because there is nowhere else to go. People might be from countries where no one is currently able to return. They might be stateless people. These people need support to regularise their status, and to live their lives and contribute like they wish to do.

Very often there is no realistic prospect of deportation, even though these people are detained and shopped between detention centres and sometimes kept there for years. It seems very illogical, as well as expensive, and therefore you think ‘Oh, OK, it’s the performative cruelty element. They’re doing this to get favour from certain kinds of voters!

Several community based alternatives to detention have been piloted by the Home Office, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), and independent charities, with caseworkers providing one to one support, including legal counselling.

UNHCR lauded the pilots as very successful, saying they enhanced the well-being and self-esteem of the participants, while being cheaper and offering better value for money for the taxpayer compared with the costs of detaining asylum seekers, and showing no evidence of a reduction in compliance with UK Home Office directives.

Jones argued that:

Although the studies seemed to conclude these alternatives had been very successful, we were very confused as the Home Office dismissed them in a single sentence, when Yvette Cooper announced, last year, that Campsfield would go ahead. We want to know on what basis these pilots are being dismissed.

Close Campsfield House, close them all

Asylum Welcome, along with other charities and campaigners, had hoped the election might herald a change in direction, particularly given that the Rwanda scheme has been scrapped, and the Labour-led Oxford City Council, Oxfordshire County Council, Cherwell District Council, and also local MP Calum Miller are all opposed to Campsfield reopening.

But Jones says they are not going to give up:

In 2015, plans to expand Campsfield House were halted, so campaigners feel a win is still possible.

Jones said:

We hope democracy counts for something, and we remain committed not only to keep Campsfield closed, but to close them all.

Actions you can take to make a difference:

- Sign and share the petition to keep Campsfield Closed here. Started by Allan, who was a former Campsfield detainee, in 2015.

- Go to keepcampsfieldclosed.uk to find out more information.

- Sign up and join the mailing list here.

- The Coalition to Keep Campsfield Closed has a monthly online meeting and is interested in hearing people’s ideas and experiences, particularly people with lived experience of detention, and those involved in other campaigns in other localities to shut these places down.

Featured image and additional images via Coalition to Keep Campsfield Closed