A study by one chronically ill and disabled person reflects the lived experience of countless people. She’s conducted groundbreaking research on herself – and countless other people could benefit – because she’s tracked how many hours a year she’s lost to living with chronic illness. And the results are staggering.

Living with ME

Cat Fraser has lived with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), a chronic systemic neuroimmune disease, since she was 24. The Canary has been documenting the illness. As we previously wrote, ME:

affects every aspect of the patient and their loved one’s lives. For many, the worst part is a worsening of symptoms brought on by physical activities, mental activities, or both. This is called post-exertional malaise (PEM). In layman’s terms, every time a person living with ME does any form of exertion, they get even sicker. It’s one of the cruellest parts of the disease, because tasks most people thinks of as ‘normal’ – like washing up – can make a person with ME really ill.

But what’s often lacking in narratives surrounding ME, chronic illness, and disability more broadly is research and evidence about the financial and time costs of living with health conditions. So Fraser, a purpose-led entrepreneur who also works for Lloyds Banking Group, has started to change this with a groundbreaking study. And the results are fascinating and concerning in equal measure.

“Well-Less” with chronic illness

Fraser has launched a project called Well-Less. She coined the term as a way of describing some people’s experience of chronic illness. As the website says, Well-Less is:

The invisible, middle ground on the health spectrum, that until Covid we weren’t talking about. …

Living, but never being or feeling fully ‘well’.

The project is a data-led study which Fraser describes as looking at:

the impact of a lack in medical care for the energy-impaired, on a patient over the course of an entire year.

The report measures the enormous amount of money, time, work and energy a typical patient is forced to spend on trying to get medical answers, care and support, in order to make up for a severe lack of understanding by the medical profession and a corollary gap in the NHS.

While data-led, her reasons for starting the Well-Less project were very personal.

“Alone and flailing”

Fraser told The Canary:

By summer 2020, as the first lockdown began to end, for me, history started repeating itself. Long Covid triggered the onset of my ME all over again. But this time I was 36 not 24, and it came with more frequent and severe symptoms that were getting worse not better, with medication. I was more aware now of my reality, thanks to all the media coverage of people experiencing symptoms that had become my normal over the years. So, I was simultaneously processing the last 10 years for what felt like the first time properly – and re-living all the grief and trauma that comes with living with post-viral chronic illness day in day out, a second time around.

On top of that was the realisation that there was still no help and support available. I was still a patient in a broken healthcare system, alone and flailing. The sad knowledge that the people closest to me still didn’t really know what these new symptoms meant for me and why I was so frightened of another ten years of this existence, was too much. I had made it to an (almost) full recovery phase of ME pre-Covid. But in the summer 2020 I came to a logical conclusion that 1. nothing had changed and 2. I couldn’t live another decade like this. Then, I was feeling suicidal for the first time ever and I wanted out.

This emotional tsunami and chronic depression lasted for several weeks, I involved my whole family in a way I hadn’t felt I couldn’t before and I took time off work to start try to heal and find a way through.

But Fraser did find a way through.

Well-Less is born

Her employer, Lloyds Bank, was accommodating. She returned to work on reduced duties and her boss let her change her ways of working to fit around her health. But Fraser still wasn’t well. So, she decided to start tracking her energy levels in a quantifiable way, to see the difference between her and her colleagues. This led to Fraser coming up with a far bigger idea. She told The Canary:

It made me think about all the other possible pieces of information that I might have that could help me bring to life other parts of this invisible patient world to life (chronic illness). Despite now being in a privileged position… I still had no answers, and I had possibly sacrificed my chances of recovery, just by using all my available energy trying.

So I started emailing the Zoe Covid App for all my symptom data; it took six months until I heard back from them. I manually collated all my bank transactions related to my health. Finally, I spent hours identifying every single email, mobile, SMS and calendar entry about my health and built a table totalling 400 rows of healthcare interactions.

At this stage, I spoke to my data colleagues about the huge quantity of data that I now had to work with and my initial findings, they encouraged me to keep exploring and visualising it to see what else came out.

So, Well-Less was born.

Assessing the cost of ME

Fraser broke the study down into four “chapters”:

1. MONEY

What was the financial cost?2. TIME

How much time was lost?3. WORK

How much work was required?4. ENERGY

How did it impact recovery?

Then, Fraser collected data across 2020 on each of these areas. The resulting report collated the information. And the results were shocking.

Five years lost to chronic illness

She told The Canary:

It was the first time I had ever thought about my life with ME in that way and why. When I added it all up, all the random days/ weeks/ months I had spent bedbound or housebound with this illness, it would in fact add up to somewhere in the region of five full years. I reflected that I often felt like I hadn’t had 36 years life experience and that I was closer to my sister’s age. Yet, as my body pains increased I also felt like it had lived 90 years and I was older than my parents.

It seems crazy now, but I had never listed all my daily health symptoms before in the way the Zoe App enabled everyone to do at the same time, as a country. Nor did I really have any idea how much money I was spending (just that I had to) and how much time I spent emailing and calling doctors (most mornings, lunchtimes and afternoons).

Money spent

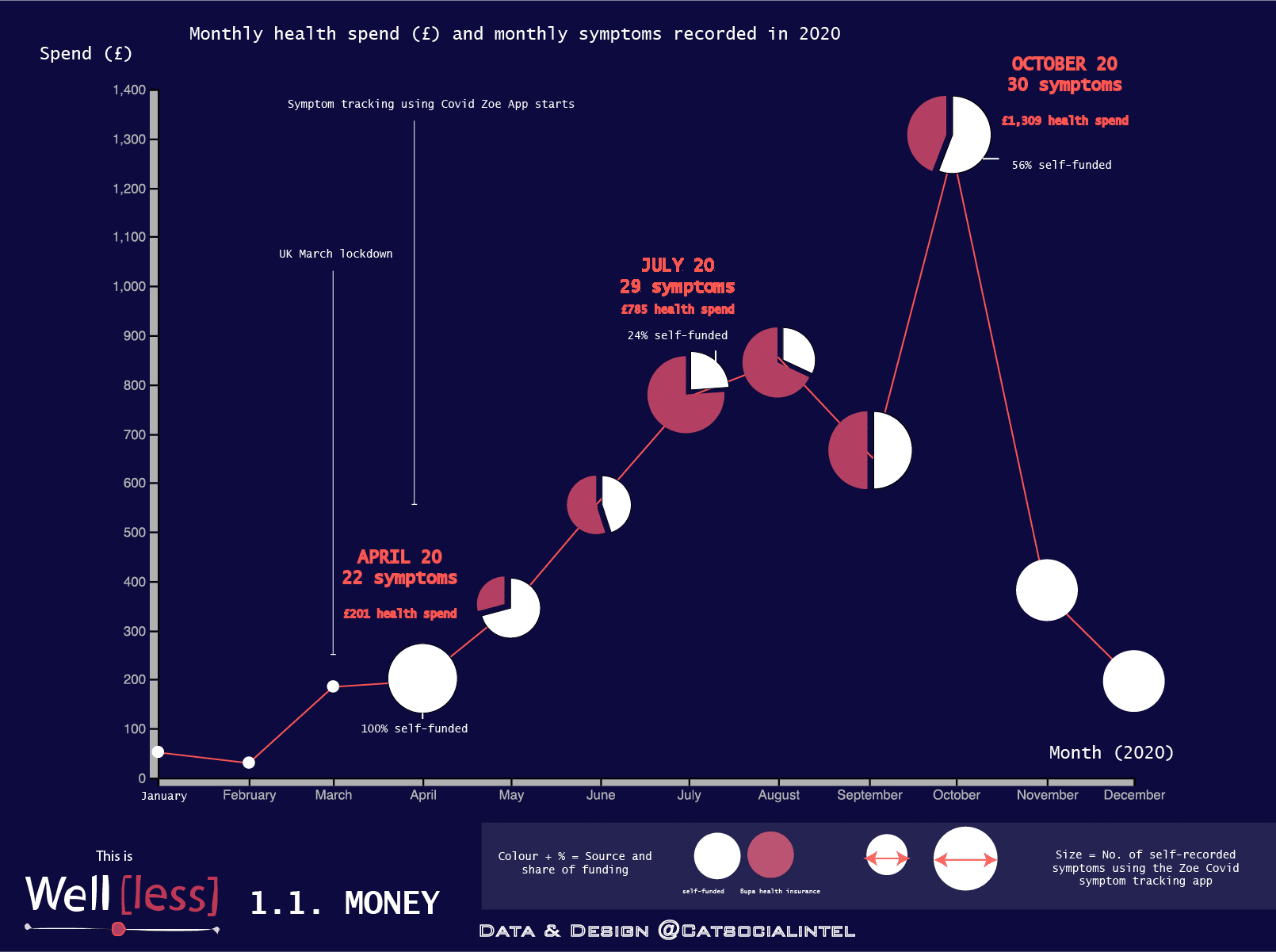

First, Fraser looked at the financial cost for her as a patient. She found that:

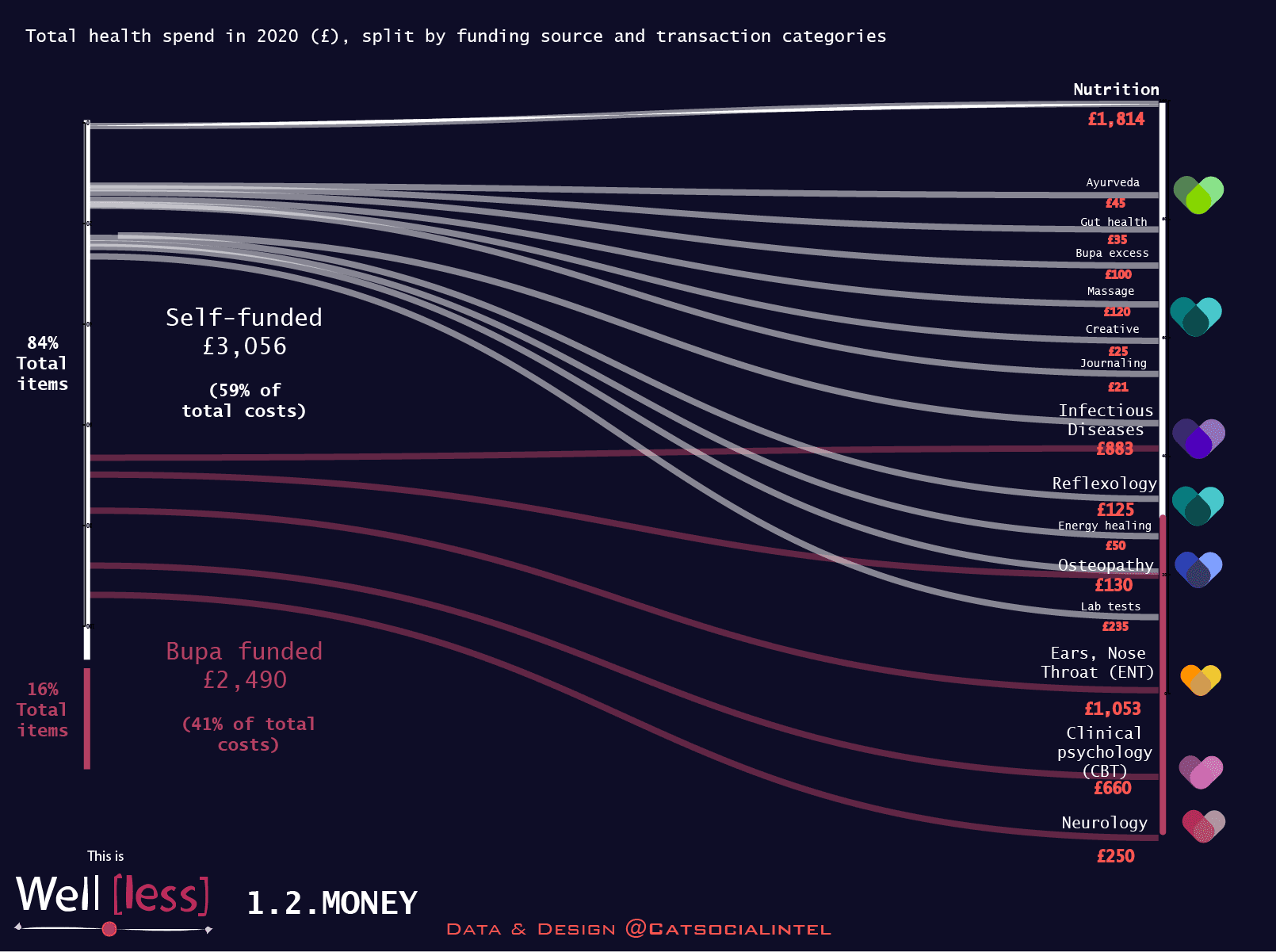

- £3.1K self-funded and £2.5K private healthcare to manage and investigate new symptoms in 2020.

- 84% of total items were self-funded, including off-plan private healthcare, and all holistic therapy (e.g. reflexology, massage, ayurveda consultation).

- Advanced nutrition, including energy supplements, probiotics and specialist gut support accounted for almost £2K spend.

- On average in April, 22 symptoms per day was recorded in the Zoe Covid Tracking app. By October, this had increased to 30.

As Fraser’s symptoms increased, so did the costs:

By far and away the biggest cost was nutrition, which included probiotics and specialised gut support – none of which the NHS provides her with:

Time spent Well-Less

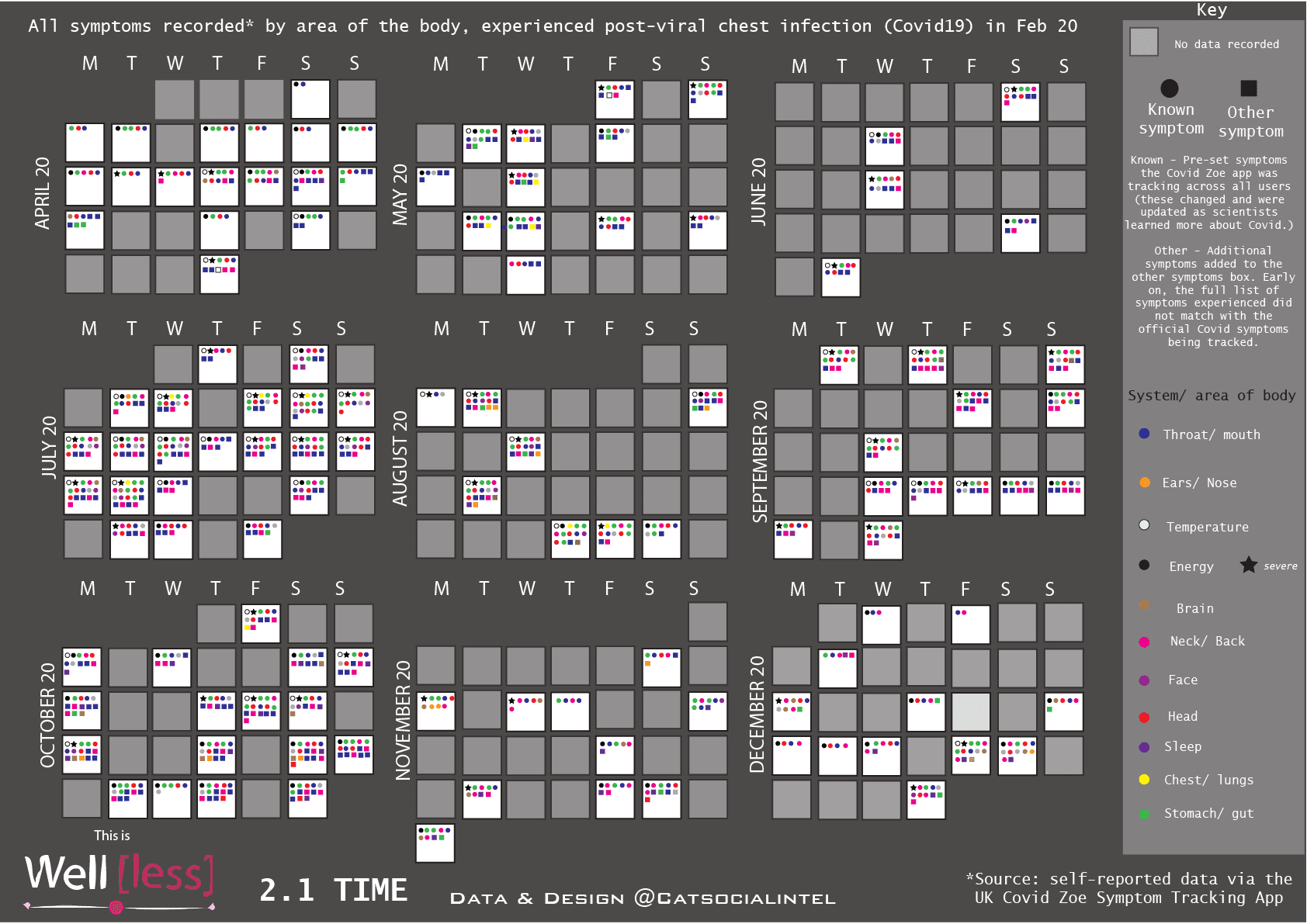

Next, Fraser looked at how often she had symptoms and what they were. She said she:

had to manage up to 30+ symptoms a day, ranging from those affecting her throat, stomach and head to chronic insomnia, chronic fatigue and depression.

And her:

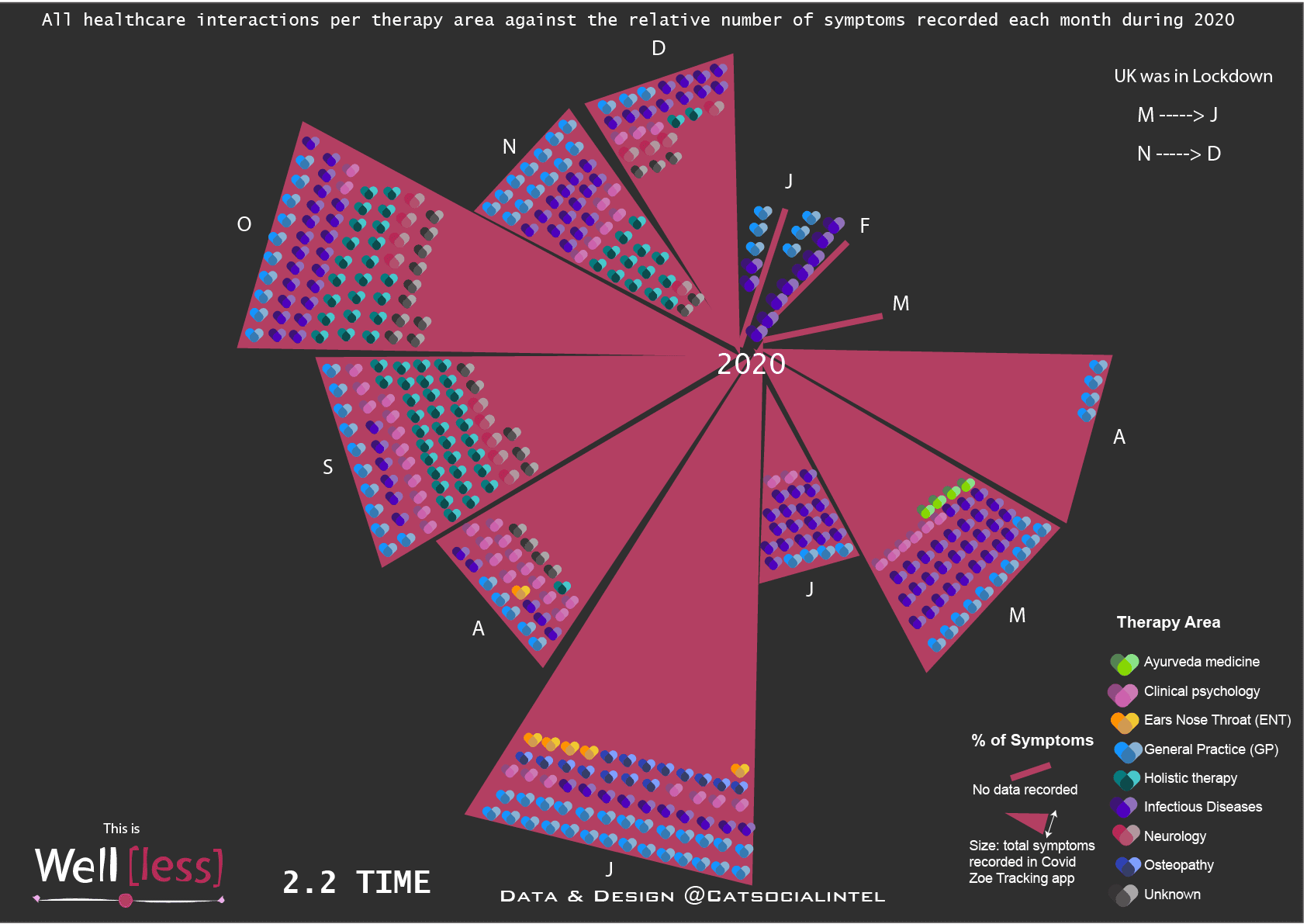

own healthcare team consisted of 35 different healthcare practitioners (including medical secretaries, labs and clinics) across seven different therapy areas.

Fraser found that from July there was an increase in symptoms, which then waxed and waned for the rest of the year. Still, Fraser found that overall there were no weeks between April (when she started tracking) and December where she was symptom-free:

An increase in symptoms was followed by an increase in medical appointments. This meant Fraser experienced the most symptoms in July but her highest number of medical appointments came in September and October:

This waxing and waning of symptoms (“flares”) is common in chronic illness. But Fraser’s data provides an interesting insight into the delay of treatment/care versus the onset of a flare.

Work and chronic illness: a job in itself?

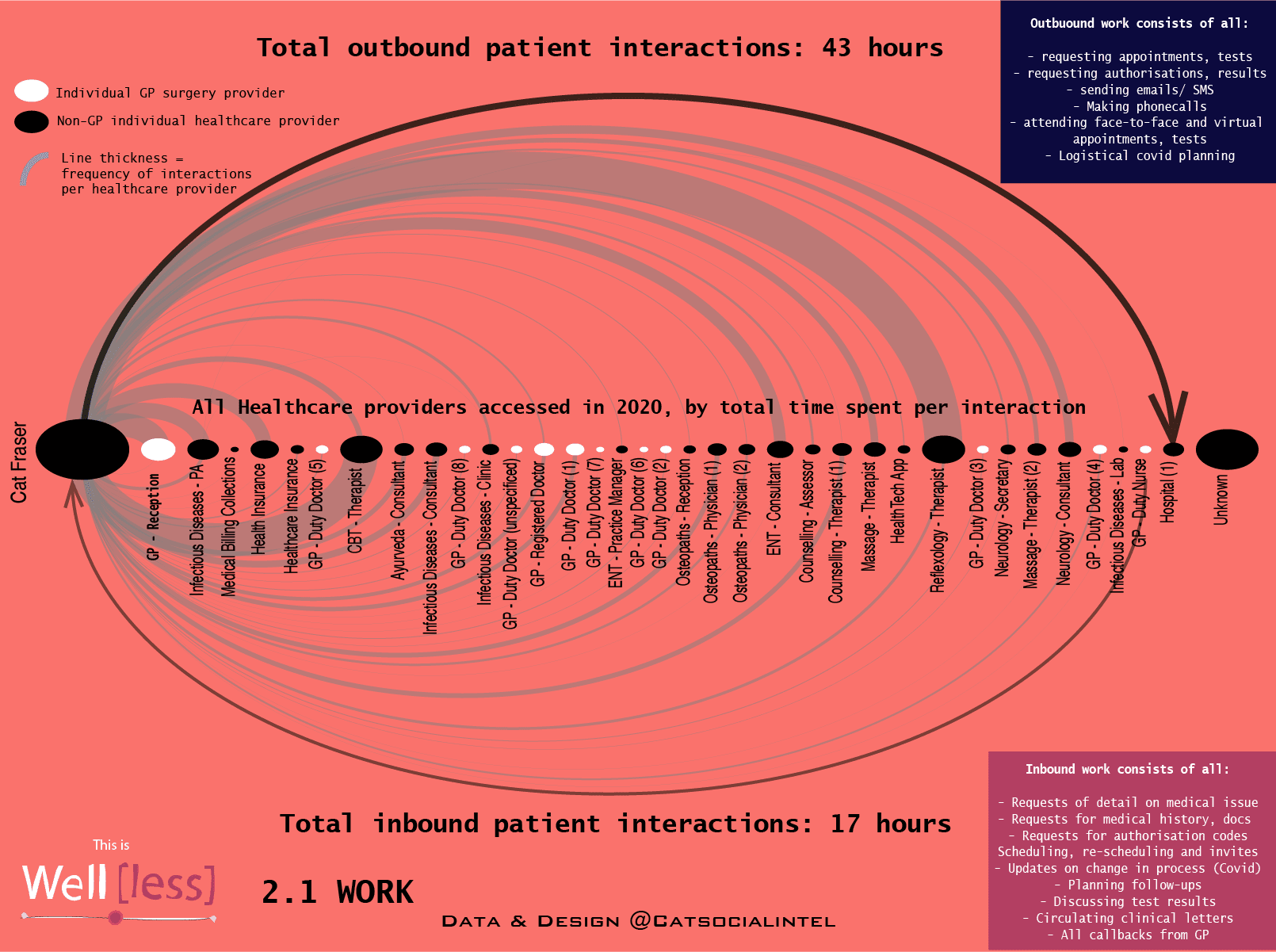

Fraser also looked at work: i.e. the time she spent on her health. She found that she had:

- 56 outbound phone calls to the GP surgery- call backs received 16 times along with 12 SMS messages.

- Appointments with x10 different GP Doctors, x1 Nurse and GP Reception – every GP in the surgery, at least once.

- Treated by 12 unique health specialists (3 non-medical) across 8 different Therapy Areas (TAs).

- Required interactions with a total of 35 unique healthcare specialists – including labs, clinics and medical secretaries.

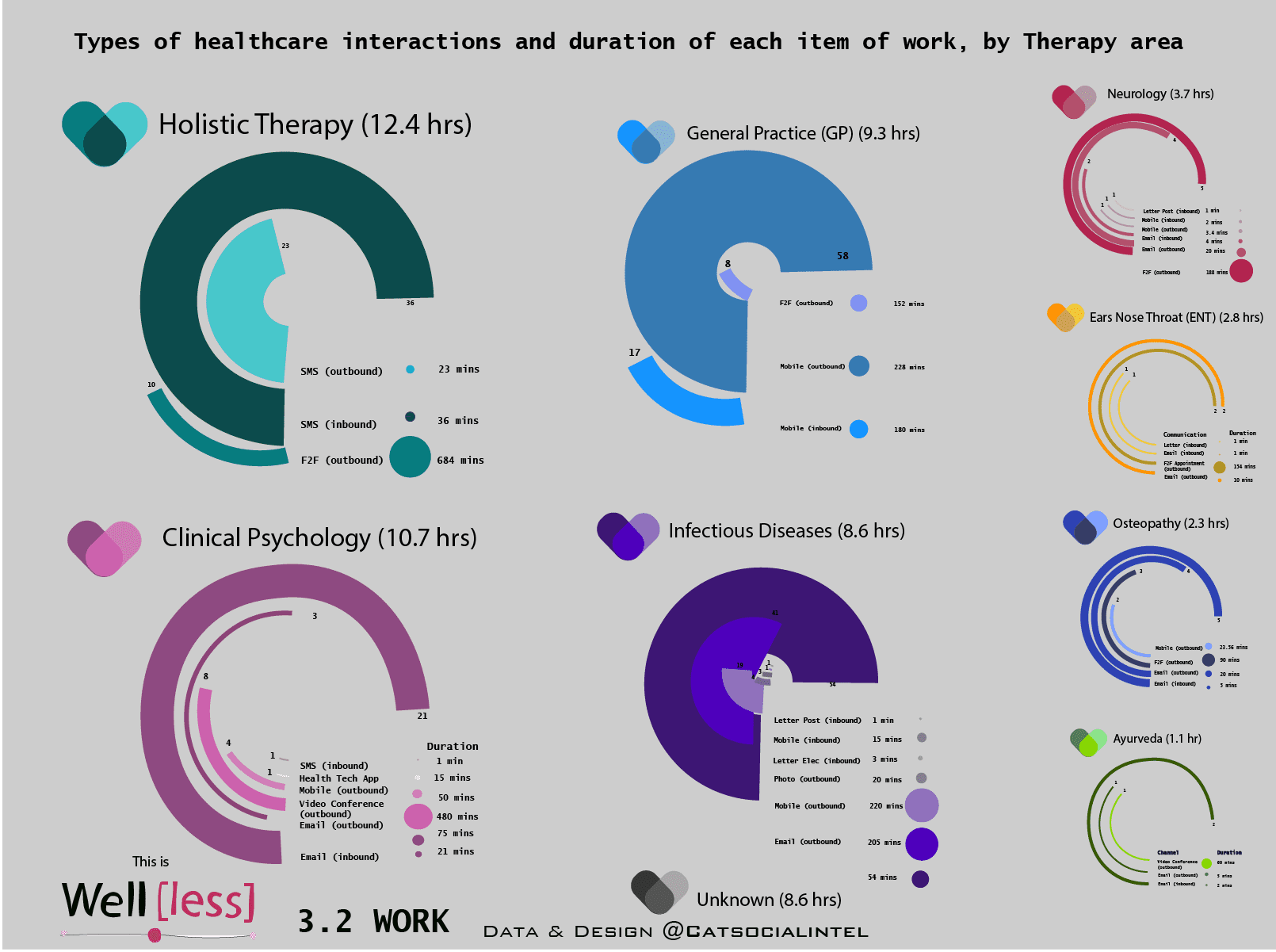

Within the data, “outbound” refers to visits to medical professionals; “inbound” means incoming calls to Fraser from medical professionals. She spent a total of 60 hours in medical appointments or on calls:

Another interesting thing from Fraser’s data was that the majority of her time was spent in holistic therapy and psychology. Time spent in neurology, ear, nose and throat (ENT) and osteopathy was all less than five hours per area:

But perhaps the most striking figures were the overall hours she spent on her health.

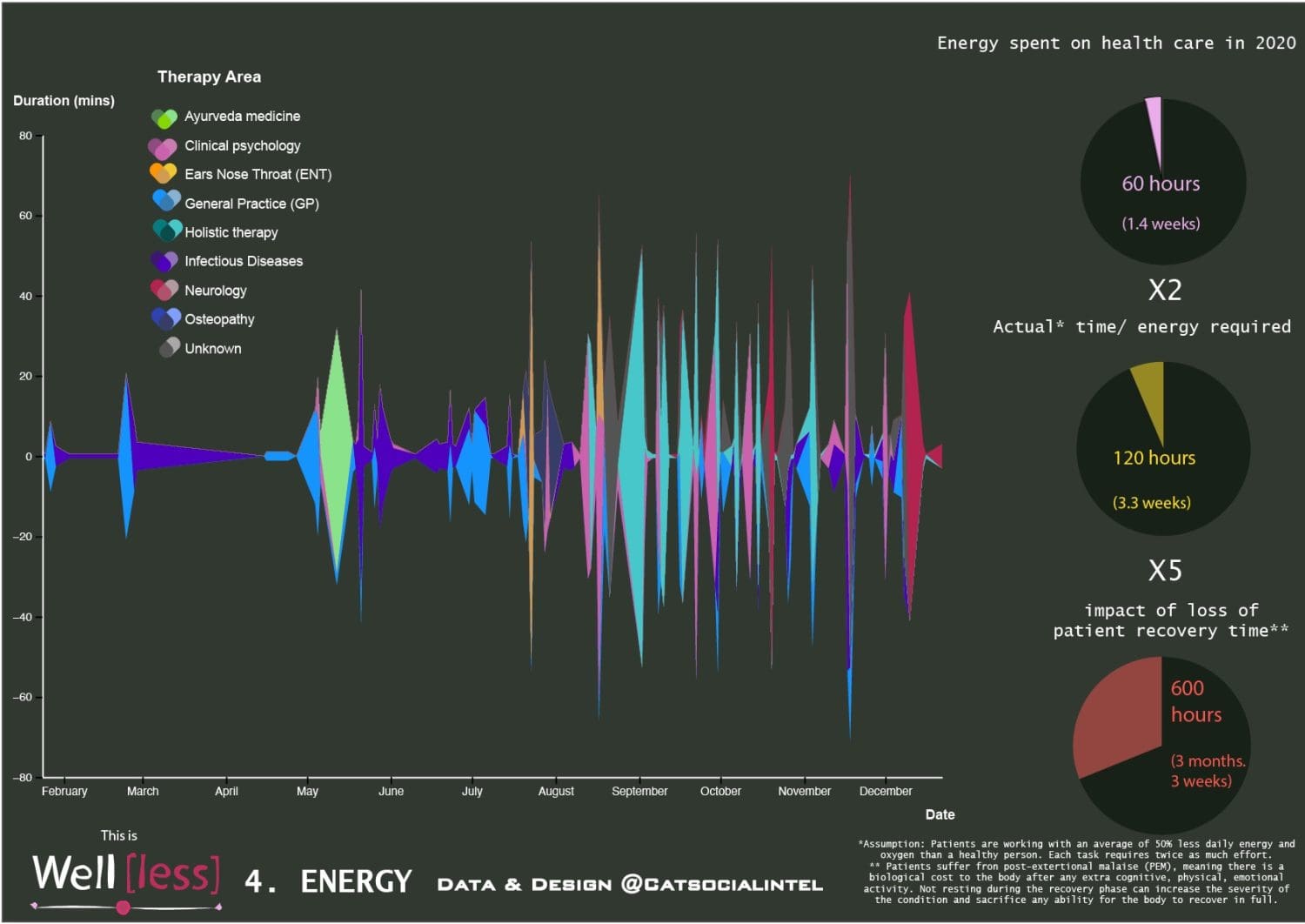

Energy: limited to the extreme

Fraser looked at the time she spent on her health. Then, Fraser calculated how much time this equated to when you factor in how ME limits her energy. Finally, she worked out the overall time lost when she included recovery time from using the initial energy in the first place. Overall, Fraser found she lost 600 hours of time in just one year either dealing with her health or recovering from dealing with it:

As she told The Canary:

This idea that if 60 hours of just working solely on my own healthcare could impact the next 90 days of my life… Well, just imagine what the rest of life’s demands that have not been designed for people who don’t recover from a virus, can do to the injured? To me?

This kind of data – covering just how much time people lose to chronic illness – is rare. But Fraser wants to change that. She wants to start getting “Well-Less” put into the language used around chronic illness:

I’d also love to see a national ad campaign for this (potentially called ‘Chronic Lives’) with charities coming out of their silos and working together to inform the public about chronic illness as a whole. I’ve put the callout to my network. But if any other creatives are looking for a pro-bono project please get in touch!

Crucially, Fraser wants to develop a “tool” (possibly app) where all chronically ill people can have access to the tools she’s created.

Tangible evidence

Fraser told The Canary:

I’m now looking for investors to enable the development of a patient data and innovation tool. It would allow people with chronic illnesses to track and measure their total patient journey. We know this type of record for patients would help validate their experiences… I’m sure it would also be a useful medical educational tool to see what is really going on underneath the bonnet. Yes we are grateful for the NHS. But the system needs to seriously address the issue that it is causing an unnecessary extra level of patient pain and trauma.

The data and insights will also enable patients to, as a community, identify new products, services, policies that they need. Of course this would all be co-created with patients. So, I’d love to hear from those who would like to be involved in the design stage!

A much-needed study

Overall, Fraser told The Canary she hopes that her work and future endeavours will lead to a sea-change; one which will:

show the impact of post-viral disease to the public and also get the science out there about ME and Covid, too.

Fraser’s study and work could be groundbreaking for chronically ill people. As it stands, apart from keeping diaries, they don’t have a quantitative way of tracking everything that happens with their health and the results. But with Fraser’s work, they could do. This could potentially change how everyone involved in chronically ill people’s lives views them – from doctors, to family, to the DWP.

But crucially, it would present the lived reality of living with a chronic illness in the round, like never before. Well-Less could be a game-changer.

Featured image via Cat Fraser