The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) has argued that a fourth coronavirus (Covid-19) booster vaccination is not required right now. And the Conservative government has now ruled in favour of mask-wearing by secondary school pupils in classrooms in England. This comes after the three devolved nations had implemented the same measure.

But there’s more to those stories that’s not being told.

Fourth booster concerns

In June 2021, The Canary reported how the effectiveness of vaccinations begins to wane after three months. That could mean that those people who were first to receive the coronavirus booster jab may now be at greater risk of infection. This means elderly and vulnerable people, as well as frontline health workers.

At the time, Independent SAGE member professor Christina Pagel pointed out that:

protection from two doses of the Pfizer vaccine may wane significantly against the Delta variant after a few months and in older people.

Indeed, one preliminary study found that “the effectiveness [of coronavirus vaccinations] against symptomatic disease started to wane from about 10 weeks”. However, it also found that “the vaccines continued to provide high levels of protection against hospital admission and death”. And that “the decrease in effectiveness appeared to be more common in adults over 65, and people who are immunocompromised”.

Nevertheless, this leaves questions about whether a fourth jab should be made available and, if so, when? The JCVI argues that a fourth jab is not needed at this point in time as the booster programme “has provided high levels of protection against severe disease from COVID-19 (both Delta and Omicron variants)”.

Even so, rising cases of Omicron mean many work absences, including NHS staff. And Pagel observed how rising cases are feeding into hospital admissions:

And yes – cases ARE feeding into rapid rises in hospital admissions. I said we should expect increases after Xmas and that is what we are seeing.

Admissions are rising in *all* age groups.

Again, these admissions are from infections pre-xmas & just after Omicron dominant 6/18 pic.twitter.com/7iv3MF427i

— Prof. Christina Pagel (@chrischirp) December 30, 2021

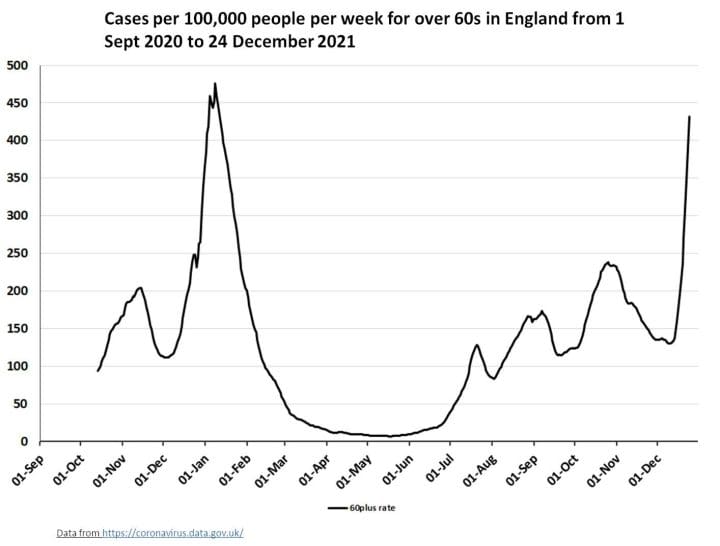

Meanwhile, this graph from government data shows the huge rise in recent weeks in coronavirus cases for over 60s:

Also, it’s reported that in London for persons aged 85 to 89, the seven day infection rate increased more than four-fold in the week to 29 December, if compared with the rate two weeks earlier. Similar figures were found for age groups below and above that grouping.

Lagging behind

Meanwhile the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has stated that latest data suggests extra protection from symptomatic disease provided by the booster. However the booster:

starts to wane more rapidly against Omicron than Delta, being about 15-25% lower from 10 weeks after the booster dose.

The UKHSA adds:

Among those who received an AstraZeneca primary course, vaccine effectiveness was around 60% 2 to 4 weeks after either a Pfizer or Moderna booster, then dropped to 35% with a Pfizer booster and 45% with a Moderna booster by 10 weeks after the booster. Among those who received a Pfizer primary course, vaccine effectiveness was around 70% after a Pfizer booster, dropping to 45% after 10-plus weeks and stayed around 70 to 75% after a Moderna booster up to 9 weeks after booster.

However, UKHSA chief medical adviser Dr Susan Hopkins stressed how those who have had the booster in the last 8 to 10 weeks are not necessarily at risk from symptomatic disease. So what of those who have passed that time period?

Meanwhile the UK lags behind Israel, where a fourth jab is being offered to healthcare workers, as well as people over the age of 60, who had their third jab more than four months ago.

More protective measures needed

There’s another area where the government is lagging behind.

I an August 2021 article in the British Medical Journal, Pagel argued that within school environments there should be:

social distancing (e.g. smaller class sizes, staggered breaks); ventilation (e.g. CO2 monitors, HEPA [high-efficiency particulate air] filters, window policies, outdoor learning); cleaning surfaces; mask wearing; keeping children within bubbles of regular contacts; frequent testing; and isolation of contacts of cases.

Those measures were in addition to vaccinations for all 12-17 year olds.

And in October 2021, The Canary published arguments by clinicians promoting mask-wearing by schoolchildren in classrooms.

But it wasn’t until January 2022 that the Department for Education (DfE) recommended all secondary school age students in England should resume wearing face masks in classroom settings. That recommendation will be subject to review on 26 January.

Oxford professor of primary care Trisha Greenhalgh commented on children’s coronavirus case rates in schools that didn’t require masks compared to those that did:

Average change in kids' COVID-19 case rates in the 2 weeks after starting school was more than double in schools that didn't require masks, compared to those that did.

93/https://t.co/IsWPNxWPD4— Trisha Greenhalgh (@trishgreenhalgh) January 2, 2022

Multi layers of protection

According to a paper published in January 2022 in Environmental Science & Technology, multiple “layers of protection” are required to reduce shared-room airborne transmission of a virus, such as coronavirus:

Our analysis shows that mitigation measures to limit shared-room airborne transmission are needed in most indoor spaces whenever COVID-19 is spreading in a community. Among effective measures are reducing vocalization, avoiding intense physical activities, shortening the duration of occupancy, reducing the number of occupants, wearing high-quality well-fitting masks, increasing ventilation, improving ventilation effectiveness, and applying additional virus removal measures (such as HEPA filtration and UVGI disinfection). The use of multiple “layers of protection” is needed in many situations, while a single measure (e.g., masking) may not be able to reduce risk to low levels.

Indeed, recommendations for additional protective measures in indoor settings were published as far back as July 2020.

According to the Times Education Supplement the DfE is telling schools they should consider combining classes because of teacher absences, which may mean more crowded sessions. And the DfE is not recommending mask wearing in primary schools.

As for transmission, senior lecturer in epidemiology Deepti Gurdasani points out that the part played by children, whatever their age, should not be ignored:

When the ONS household data shows children are 2-7x more likely to bring infection into the household than an adult & 2x more likely to transmit to contacts.

When global interventional data show that school closures are one of the most effective measures to reduce transmission.

— Dr. Deepti Gurdasani (@dgurdasani1) January 16, 2021

One option if numbers of cases worsen is to close schools and return to online learning – though that has many disadvantages.

Meanwhile the government is promising that 7,000 air purifiers will be provided to schools. But that seems nowhere near enough:

Good start but 700,000+ are required to do all classrooms.

Better get a move on.

Govt has allowed these poorly ventilated classrooms to be built due to low standards set by IAQ regulation.

It is therefore incumbent on you to fix it, not cash strapped schools. https://t.co/6L8GFpOZIZ

— Matt Butler (@mjb302) January 2, 2022

Greenhalgh sums it up:

To safely keep schools open:

– masks in class as well as in corridors

– serious attention to ventilation/filtration

– contact tracing + testing

– no indoor singing or performances

– no whole-school indoor events

– music lessons involving blowing into anything must occur online— Trisha Greenhalgh (@trishgreenhalgh) December 27, 2021

But primary school kids are still missing out on protections, placing them, their families, and teachers at risk, as this letter explains:

Today I wrote to the Education Secretary to raise the issue of Covid in primary schools, for which the government has failed to introduce any specific mitigations. This is putting our young children and schools staff at greater risk of infection. pic.twitter.com/KCG1V9pF2V

— Sir Mark Hendrick MP (@MarkHendrick_) January 5, 2022

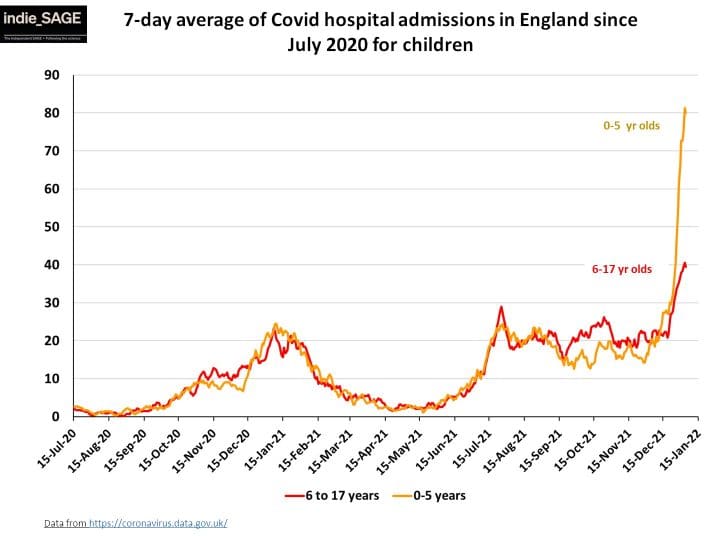

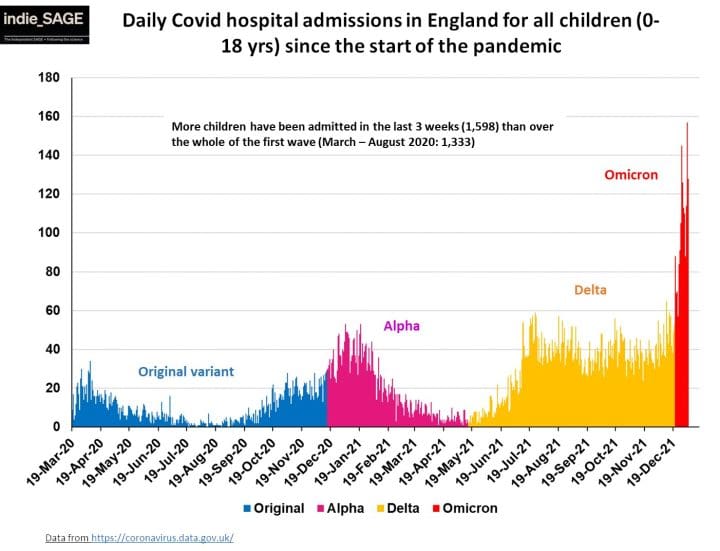

Meanwhile, these graphs show the dramatic rise in recent weeks of coronavirus hospitalisation cases for children:

Take home messages

Based on views by clinicians and studies mentioned above, the take home messages are:

- Government must provide proper ventilation equipment and other protections, free of charge, to all schools.

- Quality masks – such as FPP2 – should be provided free to every school-age child.

- Further protection measures may be needed for the elderly, the vulnerable and frontline health and social care workers.

The government needs to act on these measures swiftly in order to control the rising infection rates, protect vulnerable groups and frontline workers, and ultimately avoid further needless deaths.

Featured image via Pixabay/geralt