A minister has admitted that the government delayed locking-down at the start of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic because of scientific advice. But what he actually exposed is that far from following epidemiology or public health, the government was following contentious behavioural science: a discipline with little grounding in robust evidence. And it’s this which ultimately cost thousands of lives.

The Covid-19 Report

As The Canary previously reported, minister for the Cabinet Office Stephen Barclay was speaking to the media on Tuesday 12 October. He was defending the government over the damning cross-party report into its response to the pandemic. The analysis was by parliament’s Health and Social Care and Science and Technology committees. It branded the government’s actions “one of the most important public health failures the United Kingdom has ever experienced”.

But the report is by no means perfect. Families whose loved ones died of coronavirus have called it a “slap in the face”. This is because the committees did not involve them in the process. The COVID-19 Bereaved Families for Justice group told Sky News:

The report is 122 pages long, but manages to barely mention the over 150,000 bereaved families. Sadly, this is what we expected, as the committee explicitly refused to speak to us or any bereaved families, instead insisting they were only interested in speaking to their colleagues and friends.

Barclay tried to defend the government’s actions.

Following the science?

He was adamant it “followed the scientific advice throughout”. Barclay also refused to acknowledge that it was an “appalling error” not to introduce a second lockdown earlier, even though scientists on the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) recommended one six weeks before it was introduced. Despite the fact that the government ignored Sage’s recommendation, he still claimed:

we took action to protect our NHS, we got a vaccine deployed in record time, but I don’t shy away from the fact that there will be lessons to learn.

But something he said on the BBC provides a potential answer as to why the government’s response was so appalling. And it exposes major flaws in what the government claims is scientific advice.

Expectation versus reality

Barclay told BBC Radio 4‘s Today programme:

Well I think there is an issue there of hindsight, because at the time of the first lockdown the expectation was that the tolerance in terms of how long people would live with lockdown for was a far shorter period than actually has proven to be the case, and therefore there was an issue of timing the lockdown and ensuring that that was done at the point of optimal impact.

And so it is a point of hindsight to now say that the way that decision was shaped and how long we could lock down for… because we now know that there was much more willingness for the country to endure that than was originally envisaged.

This “expectation” around the public’s “tolerance” to lockdowns was based on advice from so-called behavioural scientists.

Enter the behavioural scientists

The Canary previously reported on this. As we noted, behavioural science is actually a branch of economics which:

incorporates the study of psychology into the analysis of the decision-making behind an economic outcome, such as the factors leading up to a consumer buying one product instead of another

This field of study has evolved from one to change consumer spending habits into something to shape public/government policy. During the pandemic, as the Covid-19 Report noted:

Behavioural advice is tendered to the Government through SAGE’s sub-group, the Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviours (SPIB). SPI-B’s first publicly known input into SAGE was on 25 February 2020 on the risk of public disorder.

The initial action plan did not consider the possibility of ceasing all non-essential contact.

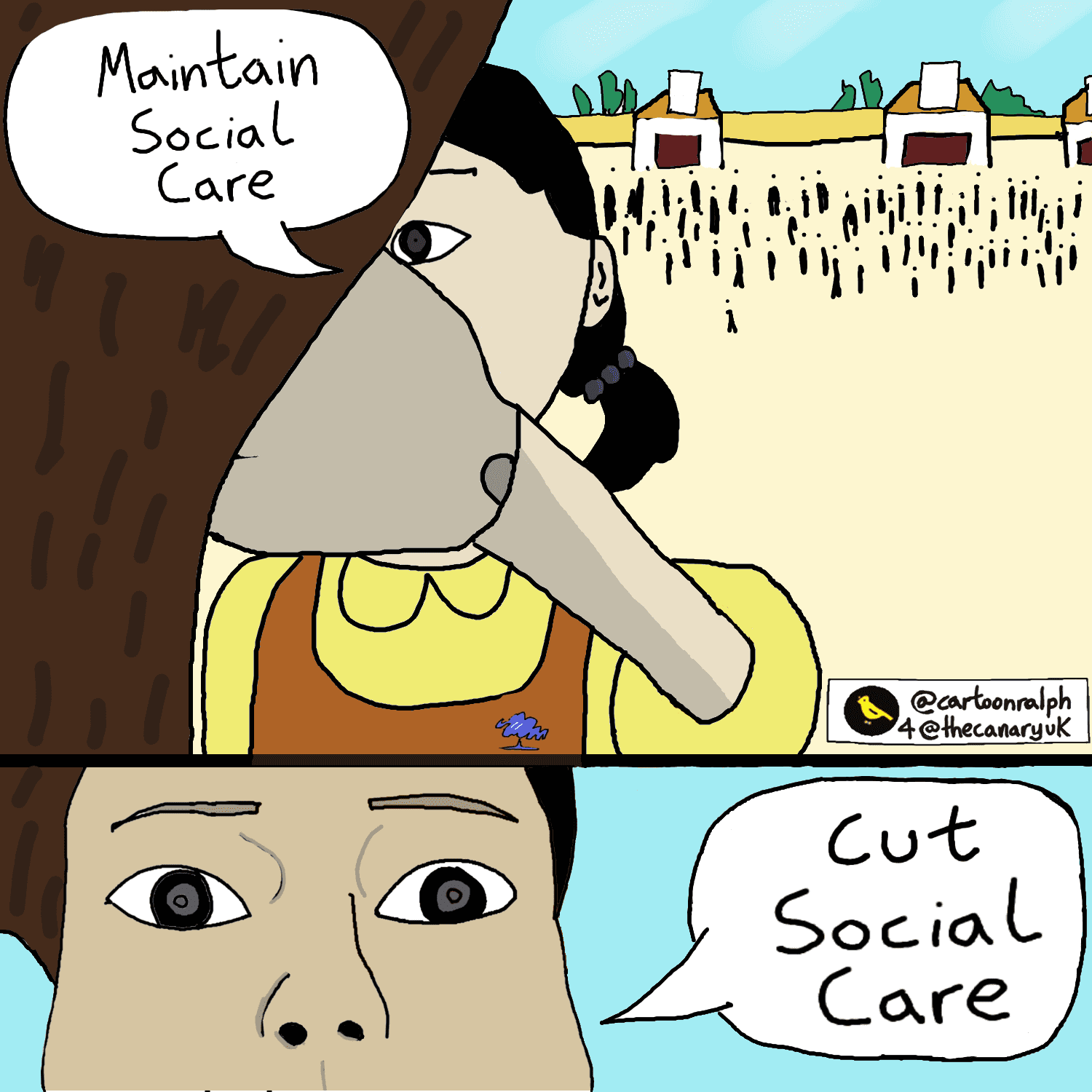

But government use of behavioural science to form policy isn’t new. Because the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has been employing it for years.

DWP: a case in point

Universal Credit was originally designed by Iain Duncan Smith and his thinktank the Centre for Social Justice. Its overriding idea was that work is the best route out of poverty. Central to this was ‘dynamic modelling’ – the idea of creating a system that changed people’s behaviour to get them into work. This is what academic Kitty Jones’s work on ‘nudge theory’ documents. Essentially, this meant the DWP cutting people’s money so they had no choice but to get a job. Or, in the case of in-work benefits like tax credits, cutting them as people started earning more. It was led by the then government department called the Behavioural Insights team, also known as the Nudge Unit.

This idea that government can force behavioural change in people by predicting how they’ll react to certain policies or rules has been central to the welfare system. But it has generally been exposed as tenuous at delivering results. For example, the failure of sanctions to get people into work, one of the main Nudge Unit policies, is the perfect example of this. A study into them found:

Benefit sanctions do little to enhance people’s motivation to prepare for, seek or enter paid work. They routinely trigger profoundly negative personal, financial, health and behavioural outcomes

‘Weak evidence’

Overall, behavioural science is contentious at best. Even PhD student Marta Kowal, who appear to have studied it, see its flaws. In an article for the website Nature, they advocated its use in a crisis like the pandemic. But they noted:

behavioural scientific evidence is weak, and in many cases we cannot even agree on the existence of some phenomena; observed effects are limited to a narrow set of stimuli and often do not generalize; reported effect sizes of experimental effects are inflated. All of that is an obstacle in building theories explaining human behaviour.

Yet despite the quantitative evidence that behavioural science’s outcomes in terms of public policy were not fit for purpose, and the overall concerns about the discipline more broadly, the government still listened to it during the pandemic.

Coronavirus nudgers

For example, on 11 March 2020, Dr David Halpern spoke to BBC News. He’s a member of SPI-B and CEO of the now-independent (but part government-owned) Behavioural Insights team. Halpern specifically said of older care home residents that:

There’s going to be a point, assuming the epidemic flows and grows as it will do, where you want to cocoon, to protect those at-risk groups so they don’t catch the disease.

By the time they come out of their cocooning, herd immunity has been achieved in the rest of the population.

Clearly, at this point Halpern (and the government) did not consider a full lockdown was necessary – nearly two months after Sage first discussed the crisis.

“Behavioural fatigue”

The government listened to the behavioural scientists, and it was concerned about “behavioural fatigue” from the public if it locked-down. Because as the government’s chief medical advisor Chris Whitty said on 12 March 2020:

An important part of the science on this is actually the behavioural science, and what that shows is probably common sense to everybody in this audience, that people start off with the best of intentions, but enthusiasm at a certain point starts to flag.

Boris Johnson’s former adviser Dominic Cummings told the Covid-19 Report committees that this was part of “false groupthink”:

One of the critical things that was completely wrong in the whole official thinking in SAGE and in the Department of Health in February/March was… the British public would not accept a lockdown

But the idea of behavioural fatigue had nothing to do with a pandemic. The evidence for it came from a study into extended service for deployed armed forces personnel.

The “weaponisation” of psychology

Then in mid-March 2020 the need for a lockdown became more apparent. But one member of SPI-B told the Telegraph that at the time, the government was concerned about the public complying with a lockdown. So, it and some of the SPI-B team had:

discussions about fear being needed to encourage compliance, and decisions were made about how to ramp up the fear.

Another SPI-B member said they were:

stunned by the weaponisation of behavioural psychology… psychologists didn’t seem to notice when it stopped being altruistic and became manipulative. They have too much power and it intoxicates them.

Behavioural science was at the heart of the government’s early approach to the pandemic. We now know that its use was a catastrophic mistake. The government’s decision to repeatedly lockdown late potentially cost countless lives.

Psychological sales people?

Sonia Sodha wrote for the Observer that some behavioural scientists:

have a tendency to overclaim and overgeneralise, based on small studies carried out in a very different context, often on university students in academic settings.

She concluded that:

The problem with all forms of expertise in public policy is that it is often the most formidable salespeople who claim greater certainty than the evidence allows who are invited to jet around the world advising governments.

And:

it is the optimism bias of the behavioural tsars that has led them to place too much stock in their own judgment in a world of limited evidence. But this isn’t some experiment in a university psychology department – it is a pandemic and lives are at stake.

Doomed to fail

As The Canary previously wrote, behavioural science is often doomed to fail because:

however much pseudoscience you push, humans are complex animals. Just because you think you can predict how we’re going to behave, that doesn’t mean you actually know for sure.

What’s not complex is that the musings of behavioural scientists whose craft has little grounding in quantitative evidence clearly turned the government’s head. And why wouldn’t it? The idea that the public can be manipulated into doing what you want it to, from the worldview that capitalism and the economy must come first, would be a winning formula for any establishment government. But as Kowal wrote for Nature (even while advocating for behavioural science’s use during the pandemic):

Caution is, indeed, much needed, and jumping straight to conclusions from correlational studies or singular experiments is, indeed, worth damning.

This is exactly what the UK behavioural scientists and government did. Tragically, the end result was countless people dead unnecessarily.

Featured image via NIAID – Flickr, the Behavioural Insights Team – screengrab and Today – YouTube