The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is under the spotlight again. This is because new research shows tens of thousands of people did not claim Universal Credit because they thought they’d look like ‘scroungers’. This was during the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic.

The results also show people thought it was ‘too much hassle’ to claim. Overall, around half a million people missed out. And it shows the DWP’s abject failure with Universal Credit.

DWP at a distance

Welfare at a (Social) Distance is a research project that’s looked into social security during the early part of the pandemic. As The Canary previously reported, the project’s previous research was about the Universal Credit £20 uplift. It noted how the increase was “inadequate” for many people. But now, the project has researched people who didn’t claim Universal Credit.

The research used various surveys to compile its data. Then, it extrapolated the data to give estimated national numbers. Finally it ran interviews with non-social security claimants.

Overall, the research estimates that around 220,000 people who thought they were eligible for Universal Credit did not claim it. It also estimated that between 280,000-390,000 people wrongly thought they were not entitled to it when they actually were. But it’s the detail of the project’s findings which is most telling.

Different perceptions

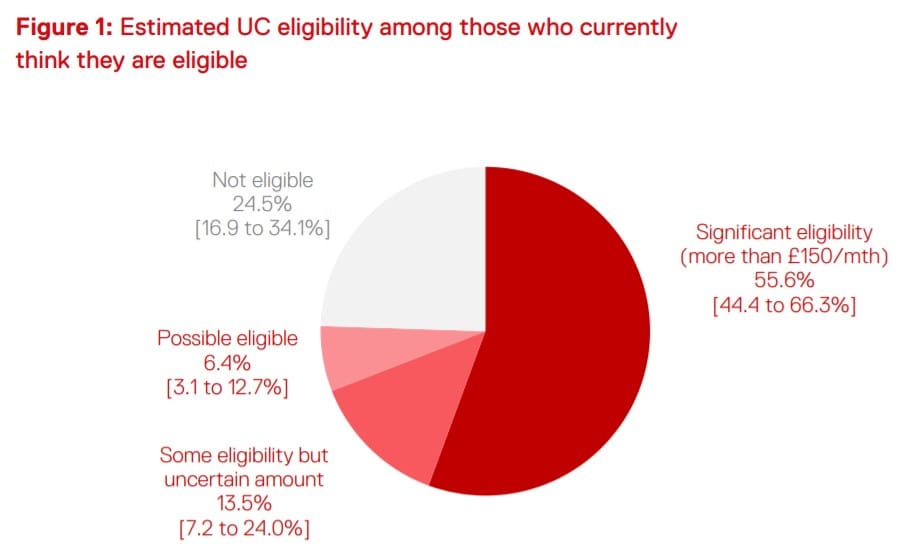

Of the 220,000 people eligible for Universal Credit but who did not claim it:

- 79.4% thought they were “probably (rather than definitely) eligible”. The project called this a “vague sense of eligibility”.

- 55.6% had eligibility of over £150 a month:

Overall, it’s estimated 100,000-110,000 were eligible but didn’t claim it.

Unsure about entitlement

Of the 280,000-390,000 people who thought they were ineligible for Universal Credit but did have entitlement:

- 58.2% said they “knew” they were not eligible.

- 28.7% said that “it had never occurred to them to claim”.

Also of these:

- 33.5% thought they were “probably (but not definitely) ineligible” to it.

- 24.6% of those “could not guess whether they were eligible or not”.

But it’s people’s reasons for not claiming which points to a wider problem in Universal Credit.

Myriad reasons for not claiming

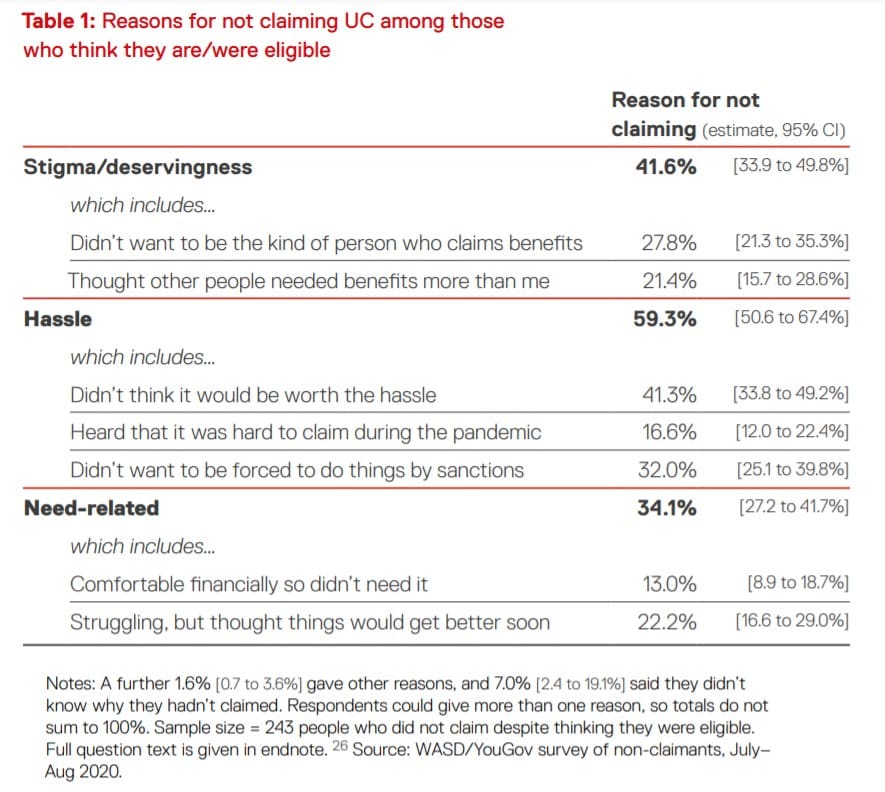

For those who thought they were eligible, the reasons for not claiming were [pdf, p11] as follows:

- 59.3% reported the “hassle”.

- 41.6% said the “stigma/deservingness”.

- 34.1% said it was to do with “need”:

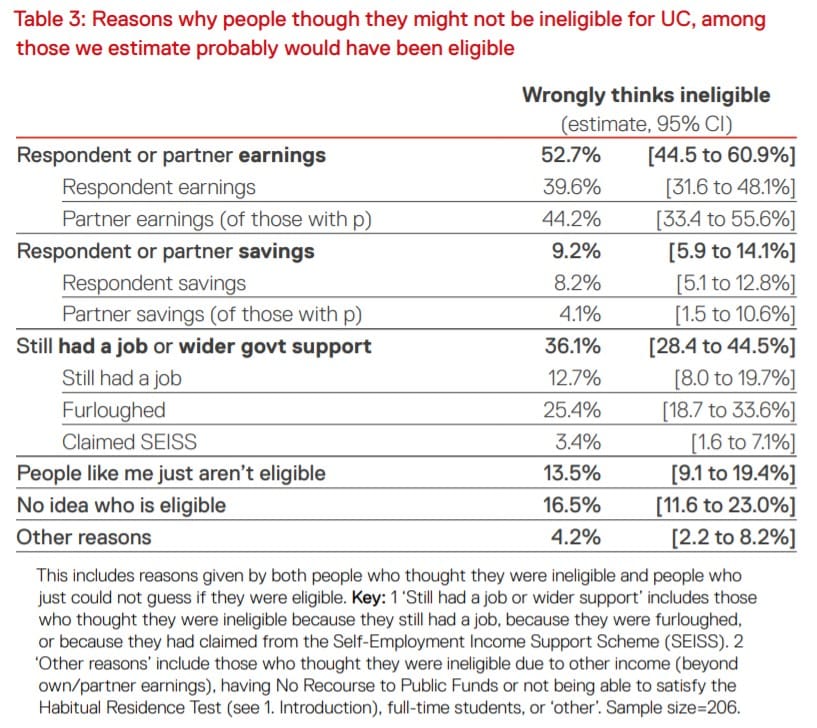

Then, for those who thought they were ineligible, reasons that were given included:

Then, for those who thought they were ineligible, reasons that were given included:

- 52.7% thought earnings made them ineligible.

- 36.1% still had a job or got other government support.

- 16.5% didn’t know who was eligible:

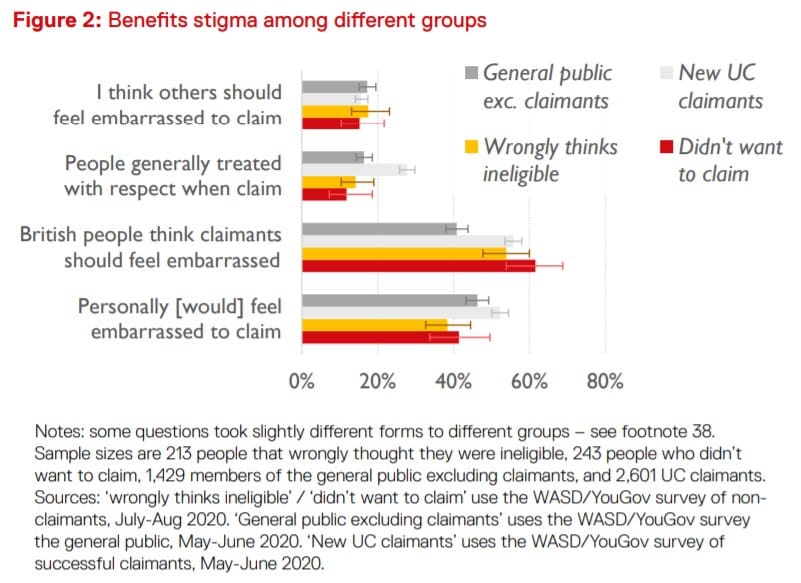

One of the main points that came out of the research was benefits stigma.

Stigmatisation

It broke stigma down into three types:

- ‘Personal stigma’: a person’s own feeling that those claiming benefits should be looked down upon.

- ‘Stigmatisation’: this is the perception that other people will look down upon those claiming benefits.

- ‘Claims stigma’: this is the feeling of being looked down upon that happens while claiming benefits. This can come from issues such as a lack of privacy, but is often associated with whether people feel Jobcentre/DWP staff are looking down on them.

The project found that around 40% of people who didn’t make a claim were personally embarrassed too. 50-60% of people cited the British public’s attitude towards benefit claimants as a reason:

The research also had people’s stories about this.

‘Scroungers’

Younger people generally reported feeling less stigma. But this was not the same in other groups. As the Welfare At A (Social) Distance reported wrote:

Ezekiel (30–49) worried that if he claimed, others would “laugh at me the way I laugh at them [benefit claimants]”. Feelings of stigma were more common amongst older respondents, but even some younger respondents such as Tom (18–35) said they deliberately had not asked any of their friends for advice when they considered claiming.

The report also talked about migrants:

Benefits stigma was also more common amongst the migrants that we spoke to. It seemed that migrant non-claimants felt a need to distinguish themselves from ‘welfare tourists’, as found in other research. For example, Marianne (30–49) had heard her friends talk about migrants only coming to the UK for benefits, which made her keen to avoid the benefits system: “Because I’m not British, I don’t want to feel like I’m here to take anything from others.”

Complex views

Overall, the report noted the complexity of people’s views on stigma:

These views were complex and sometimes ambivalent. It was not just that different people held different views, because even a single person could hold conflicting views. For example, Steve (50–65) talked about not being a “dole scrounger”, but at the same time was annoyed with other people who viewed benefit claimants as “freeloaders”. Similarly, Tyrone defended people’s right to claim benefits, but he also contrasted his own ‘genuine’ previous claim for a back injury with those who fraudulently claim or are not really seeking work: “There’s genuine people that I saw that were genuinely looking for work, and then there’s certain people that have no interest in finding a job”

Of course, the end result of all of this was the DWP leaving people financially bereft.

Financial chaos

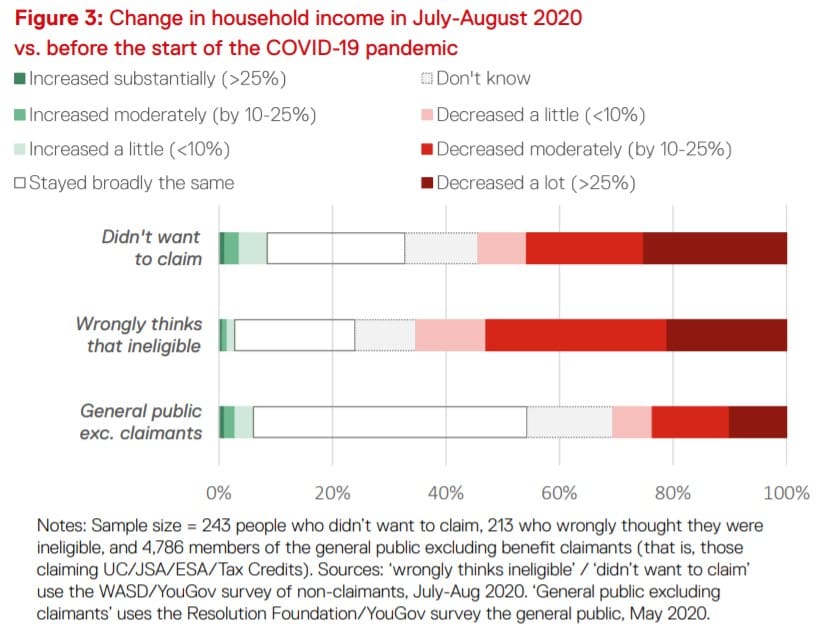

The report found that people who didn’t claim Universal Credit lost more money during the pandemic than the general population:

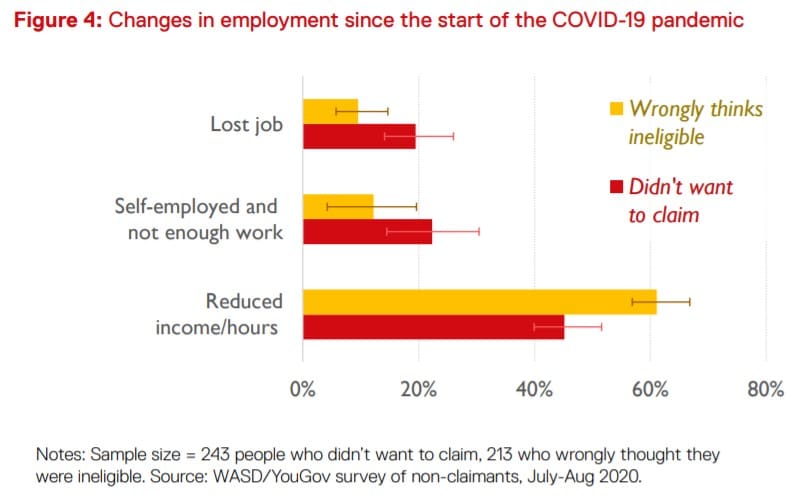

Most commonly, people were still working in some way:

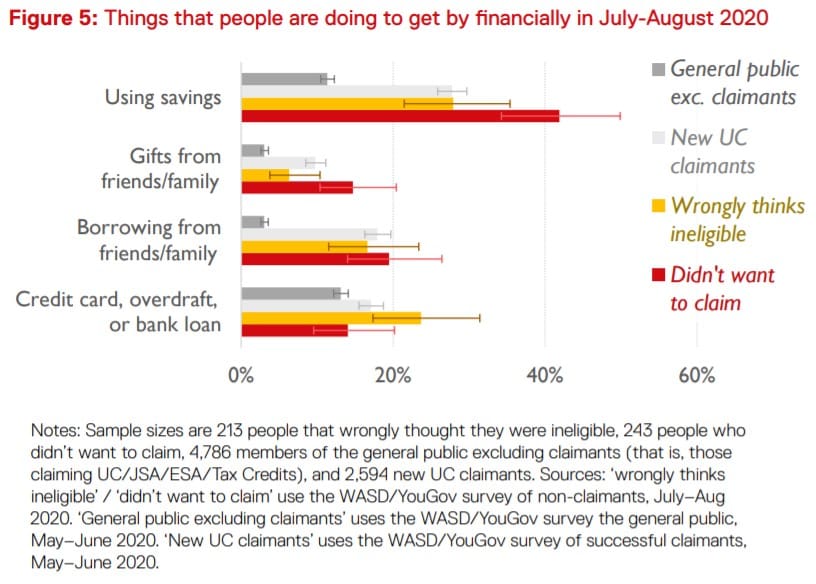

This often meant they had to get money from other sources or use savings more than others:

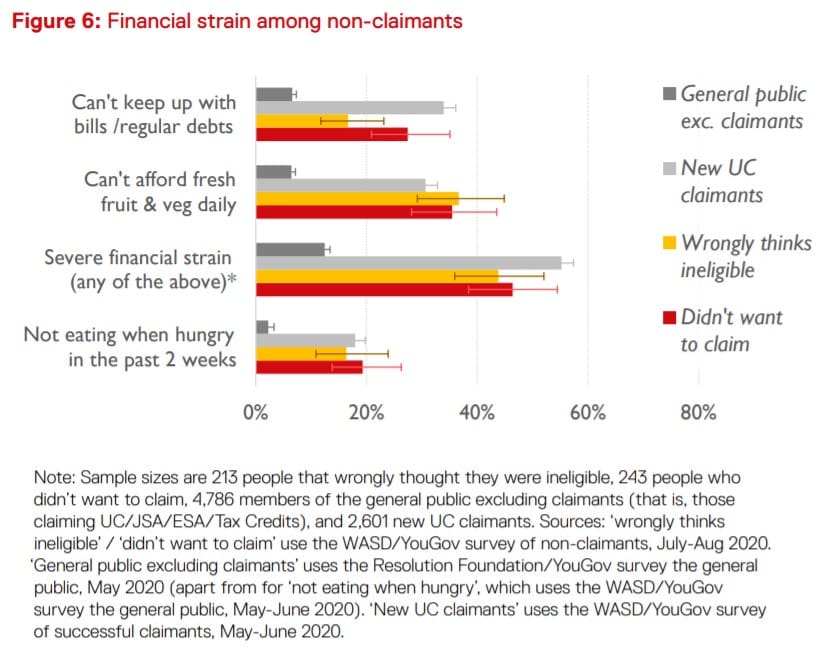

Overall, the lack of claiming had a profound affect on people. Nearly half of all people the project spoke with reported at least one of the following:

- Unable to afford to eat fresh fruit and vegetables daily.

- Falling behind on rent/mortgage payments.

- Unable to keep up with other bills/debt payments:

The government says…

Overall, around half a million people who were probably entitled to Universal Credit didn’t claim it. People’s reluctance seemed to be due to uncertainty about the system and stigma. The Welfare At A (Social) Distance project made some recommendations for the government:

- “Ensure that people claim the right benefits as quickly as possible”.

- “Correct misperceptions about the benefits system”.

- “Attempt to address benefits stigma”.

Meanwhile, the government told the Guardian that:

We want to make sure that everyone receives the support to which they are entitled and we’d urge anyone who thinks they’re eligible for universal credit to apply. Universal credit is designed to be as accessible as possible and has provided a vital safety net for six million people during the coronavirus pandemic.

But of course, what the report shows are problems which have been plaguing the DWP for years.

Plagued by problems

When it launched Universal Credit in 2013, its aim was to simplify the benefits system. But in reality, the roll out has been beset by problems. Not least in these have been court cases the DWP has lost. These have been because Universal Credit has left people worse-off. So, it’s of little wonder that during the pandemic people may have felt Universal Credit was too complex. Also, the DWP and government designed Universal Credit to be punitive – so as people wouldn’t want to claim unless circumstance forced them to.

The stigma surrounding claiming social security is nothing new, either. As The Canary previously wrote, the demonisation of claimants has been decades in the making: from Tony Blair putting worklessness as an individual problem and not a system one, to TV programmes like Benefits Street. And in 2017, a UN committee chair commenting on how the UK’s welfare state treats sick and disabled people said:

the government and the media “have some responsibility” for society seeing disabled people as “parasites, living on social benefits… and [living on] the taxes of other people”. And she said these “very, very dangerous” attitudes could “lead to violence… if not, to killings and euthanasia”.

The Welfare At A (Social) Distance report is the culmination of years of intentional government degradation of the UK’s welfare state. In this instance, the DWP has left people struggling to eat; ultimately because of government and media propaganda, and also a system which seems intentionally complex.

Yet while the pandemic has exposed the faults in the system to a wider audience, nothing here is new. And it will take nothing less than a seismic shift in the way society operates for anything to actually change now.

Featured image via NIAID – Flickr and Wikimedia