Stephen Fry has produced a compelling video exposing the flimsy factual foundations upon which Vote Leave launched its 2016 Brexit campaign. And it’s a compelling demonstration of how propaganda infects society with fear, baseless myths, and falsehoods.

The “mythical dragon” of the EU

Fry sets out how a Eurosceptic British media “conjured up” a “mythical EU dragon”.

He argues that the shaping of public opinion on the EU is an example of ‘forced perspective’: where deceptive framing creates false assumptions. Such assumptions, he states, are “very dark and some comical”.

Racism in the British media

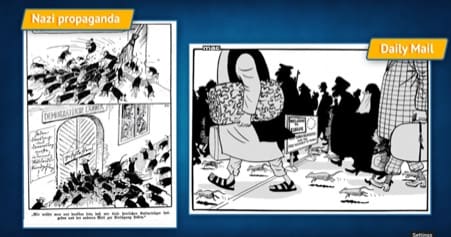

In a darker example, Fry cites the opinion of the chief of UN human rights who once called on UK authorities to curb incitement to hatred after tabloids compared immigrants to cockroaches.

The UN claimed this demonstrated an “underbelly of racism” reminiscent of tactics used by Nazis:

And aside from such extreme examples, Fry argues that the British media’s endless drip-feeding of anti-immigration stories over the years meant that:

Brexiteers sailed in on fears built over decades.

Unsurprisingly then, the UK media is “by some way” the least trusted in Europe. And on EU myths specifically, the EU has compiled a stunning list of fake news examples found in UK media.

Leave’s scaremongering imagery

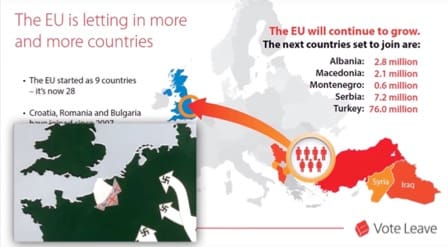

Fry also gives examples of slick misleading graphics deployed by the Vote Leave campaign to spread fear of immigration in the EU.

In the first graphic, countries such as Turkey are described as “set to join the EU”. This is despite Turkey applying over 30 years ago and it appearing highly unlikely it would be accepted anytime soon.

Secondly, to enhance the fear, Vote Leave included Syria and Iraq in the graphic, despite neither of them applying to join the EU:

Note also how, in this graphic, Syria and Iraq are coloured almost identically to Turkey. The arrow depicting the hypothetical migration of people to the UK, meanwhile, is coloured similarly, with the text stating “the EU will continue to grow”.

The arrow also creates the impression of an aggressive invasion reminiscent of the Dad’s Army intro.

Fry points out the implicit racism of these campaigns. And he notes how Vote Leave blocked out the only white face with a logo in the poster below:

Taking back control?

Fry also attacks the idea of ‘taking back control’ from the EU and reasserting British sovereignty. He asserts that the EU has been portrayed “like an alien force taking over Britain”.

Yet the data shows UK governments were in favour of 95% of EU laws passed and only opposed 2% of them.

Elsewhere, the flip-flop change in opinions by those desiring us to ‘take back control’ before the referendum has been brutally exposed:

Don't just take Mr Fry's word for it.

The same people who championed the Brexit vote in 2016 are now telling us that everything they promised was a lie.https://t.co/I9R0Ncalqg— Femi (@Femi_Sorry) November 30, 2018

But are there problems with Fry’s analysis?

Fry’s video is undoubtedly valuable. But similar fact-based initiatives preceded the referendum and arguably failed. So facts might not be as sacred as Fry hopes.

For example, Fry’s premise that the above messaging resonated simply because people “had suffered years of income stagnation while the rich had grown richer” is questionable.

Because, although it’s true that poorer households were far more likely to vote for Brexit (as the book National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy argued), richer demographics also voted for Brexit in large numbers [pp22-23]. Many people were clearly voting based on beliefs, not just in protest against economic deprivation.

And as academic Bobby Duffy of King’s College London argued about Fry’s video:

does this simple mythbusting approach work to change minds? The evidence suggests it doesn’t, because… it misses a large part of the point: that our misperceptions are often more emotional than rational.

Moreover – and this might make uncomfortable reading for those who favour immigration – he insisted that:

the framing in Fry’s video ignores the wider concerns people had about the speed of change in their communities, beyond the economic and fiscal impacts.

Overall, he felt that the undertone of Fry’s argument is that:

‘you only voted to leave because you were duped’, and therefore your own perceptions of your experience are worth little.

A welcome contribution

Despite its limitations, though, Fry’s intervention gives us a greater understanding of the propaganda dynamics that led to the Brexit vote.

And if a second referendum takes place, he explains idealistically:

Perhaps in a final vote, facts would start to overcome fears. Wouldn’t that be a win for informed democracy?

Facts and reason, however, may not always be enough to overcome ingrained beliefs and emotions. And we need to be aware of that. But that awareness doesn’t mean we should stop trying to ensure that facts and reason win out.