The debate in the House of Commons over the latest terrorism bill lasted over three hours on 11 June 2018. And the atrocity at the Ariana Grande concert on 22 May 2017, where 22 adults and children were killed by a suicide bomber, was repeatedly invoked.

But one Tory MP in particular put his foot in it by using a “factually flawed” understanding of the Manchester bomber to defend the bill.

Was the Manchester bomber self-radicalised online?

The debate was on increasing powers to the state under the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Bill 2018. During the discussion, Conservative MP Eddie Hughes said:

people can now be radicalised in their home in the UK by reading literature produced in other countries. We need to ensure that we act appropriately to prevent the dissemination of that sort of information.

The concept that some ‘information’ must be banned has been part of UK ‘counter-terror’ laws and strategy for the last 18 years.

Hughes continued:

To return to the bomber in Manchester last year, that person acting alone, thanks to the internet and those illicit sources, had the opportunity to learn how to make a bomb using items that are freely available in this country. Without physical contact with other people, they were able to garner the information, be radicalised and carry out a dreadful act. It is surely essential that we do everything we can to tidy up the law in this country to prevent that.

Despite a long speech by home office minister Ben Wallace during the debate, at no point did he or any other MP contradict Hughes’s statements. In fact, he suggested that people who say “don’t trust the state” were essentially akin to “recruiters of extremism”.

Investigative journalist Nafeez Ahmed, however, told The Canary that Hughes’s remarks were “factually flawed”. Ahmed published a report with British analyst Mark Curtis entitled The Manchester Bombing: Blowback from British state collusion with jihadists abroad on 3 June 2017.

Far from spending his time ‘home alone’, as Hughes suggested, Manchester bomber Salman Abedi actually went to Libya to fight – with the implicit support of the British state.

Radicalised by the British state?

Ahmed told The Canary:

The Tory MP’s defence of the new bill is factually flawed. It is now a matter of record that the Manchester bomber did not act alone, and was not solely radicalised by reading online materials. To the contrary, it is clear that he was radicalised in the context of the British government’s military offensive in Libya.

He then tore apart the arguments justifying the 2018 bill:

By claiming absurdly that Salman Abedi was radicalised at home and learned to make a bomb on the internet, the official Tory position carefully obscures the mounting evidence of the British government’s own role in creating an open door between vulnerable Britons and Islamist militant networks abroad, in this case in Libya – which appear to have been the chief source of both ideological radicalisation and military training received by the Manchester bomber.

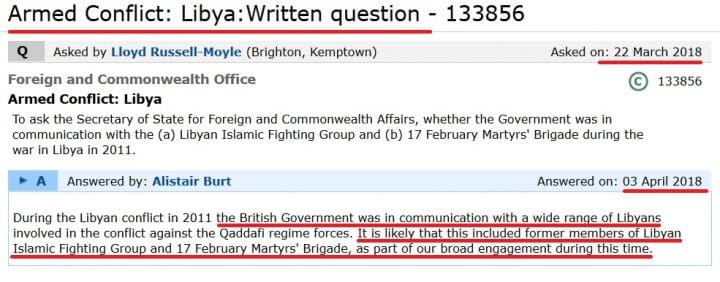

While many questions remain regarding what possessed Abedi to undertake the Manchester bombing, we know that he joined and fought with the al-Qaeda-linked Libyan Islamic Fighting Group in the war in Libya. And the UK government itself admitted it ‘likely’ had contnections with the very same groups.

This flat-out contradicts the idea of Abedi being a ‘lone wolf’ radicalised at home. Especially given there is no clear or universally accepted [pdf, page 11] definition of the meaning of ‘radicalisation’, despite its regular usage.

“Self-serving” definitions of radicalisation

Ahmed also told The Canary that the 2018 bill will do nothing to “address the real factors that radicalised Abedi”. And he continued:

It will, however, permit further draconian infringement of fundamental civil liberties by opening the way to the criminalisation of people based on things they read online, deemed by the state to be conducive to radicalisation.

Finally, he concluded that:

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the government is capable of adopting politicised shifting definitions of ‘radicalisation’ and ‘terrorism’ which are unreliable and self-serving.

This point is supported by Ahmed’s work exposing Britain and Turkey’s alleged complicity with far-right Islamist militants, including Daesh (Isis/Isil).

Inquiry

The government has offered the public only a very brief time to send in their concerns regarding this latest terror bill. The Joint Committee on Human Rights has put out a request to the public for comments. And from now until 27 June, the committee will be taking submissions regarding people’s human rights concerns. Submissions should be no more than 1,500 words.

Disclosure: The author of this article volunteers with the Campaign Against Criminalising Communities.

Get Involved!

– This is The Canary‘s third instalment about the 2018 terrorism bill. Here are Part 1 and Part 2.

– Read about the opposition to anti-democratic terrorism legislation.

– Tell the joint committee your thoughts (politely) about any human rights concerns you may have regarding this bill.

– Write to your MP and tell them to oppose the Counter Terrorism and Border Security Bill 2018.

– Support The Canary and support independent journalism like this.

Featured image via screenshot and Transport Pixels – Wikimedia

![The Grenfell silent march. One year on. Forever in our hearts. [IMAGES]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Grenfell-Silent-March14-6-18FB-2.jpg)