In 2000, the UK passed the Terrorism Act 2000 – one of the most draconian pieces of legislation in its history. Now, the state wants even more power.

Counter-terrorism and border security bill 2018

The Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Bill 2018 is a dangerous new development apparently aimed at further criminalising speech and dissent in the UK. It was first revealed on 6 June, with no debate. Its second reading is scheduled for 11 June 2018.

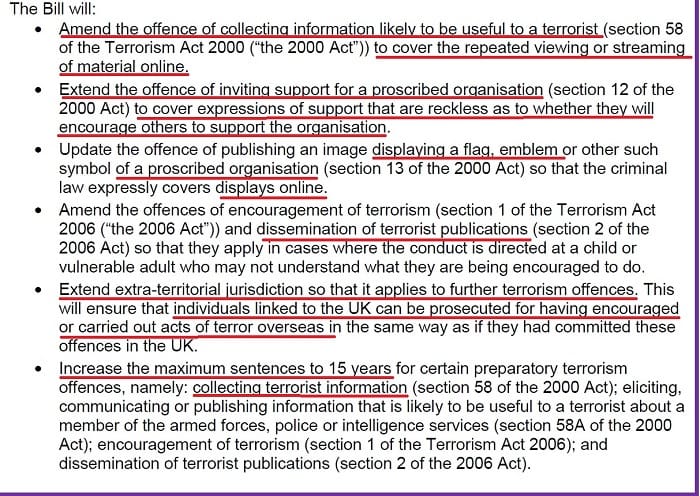

Under the plans, the definition of “inviting support” for a banned group will include:

expressions of support that are reckless as to whether they will encourage others to support the organisation.

The offence of “collecting information likely to be useful to a terrorist” will now also cover [pdf, p6] “viewing or streaming of material online”.

And while the current penalty for these ‘offences’ is up to 10 years of imprisonment, the 2018 bill seeks to increase many maximum punishments of such ‘terror’ offences to 15 years.

The 2018 bill also updates the offence of publishing [pdf, p1] an:

image displaying a flag, emblem or other such symbol of a proscribed organisation… so that the criminal law expressly covers displays online.

This will include a photograph taken in a private place.

It’s important to remember here that many organisations engaged in armed conflicts for self-determination with oppressive regimes in Palestine, Turkey, and Sri Lanka have been labelled ‘terrorist’ organisations.

“Shrinking public space”

In April 2017, the EU parliament recognised the worsening problem of a “shrinking public space” and reported [pdf, p6] that the:

global clampdown on civil society has deepened and accelerated in recent years. Over a hundred governments have introduced restrictive laws limiting the operations of civil society organisations (CSOs)…

The closing space is part of a general authoritarian pushback against democracy…

A 2017 discussion paper on this “shrinking space” says [pdf, p8]:

Attacks on freedom of expression and association… are invariably justified on the grounds that certain political activities may be legitimately curtailed by the state, whether under the banner of protecting the ‘public interest’, ‘social cohesion’, ‘national security’ or ‘counter-terrorism’.

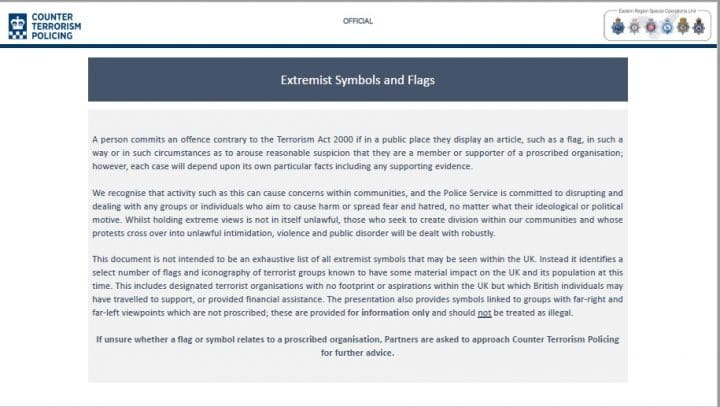

How the British state currently views extremism and terrorism

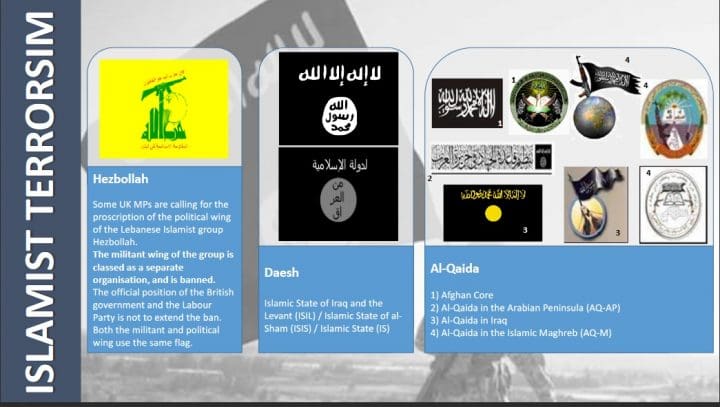

The Canary recently exposed an official counter-terrorism document entitled Extremist Symbols and Flags.

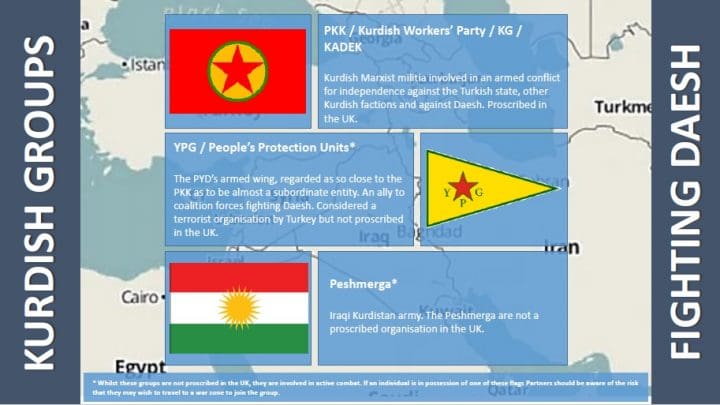

This document lumps very different groups together as ‘extremist’ organisations – listing anti-fascists and Kurdish-led anti-terror fighters (including the PKK and the YPG/YPJ) alongside their foes in Daesh (Isis/Isil), al-Qaeda, and neo-nazi groups.

Anti-fascists, the YPG, Anonymous, and the Hunt Saboteurs Association, however, are marked with an asterisk as “not yet proscribed in the UK”.

Both the YPG (in Syria) and the PKK (in Turkey) are guided by the philosophy of democratic confederalism. As The Canary has reported comprehensively in recent years, this is a secular ideology encouraging direct democracy, ecology, and feminism, which can be seen in action today in northern Syria (aka Rojava).

Terrorism Act 2000

Under the 2000 act:

- Groups can be proscribed (banned) as terrorists – along with images, symbols or flags associated with them.

- Terrorism is defined so widely as to criminalise both resistance to oppressive regimes and the provision of non-material support to banned groups.

- Failing to report ‘terrorist’ activities to police is a crime.

- Language that ‘glorifies‘ terrorism is a crime.

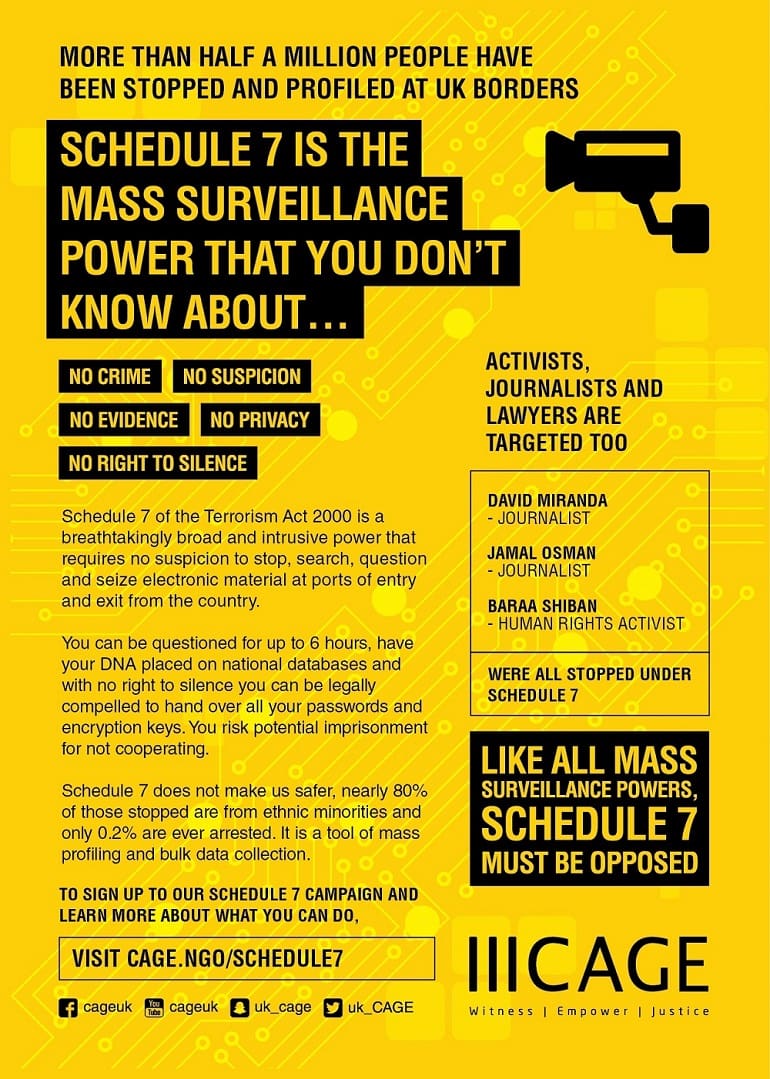

- Officials can stop and search people at any port (under Schedule 7 of the act) without suspicion of any wrongdoing.

- Anyone questioned under Schedule 7 commits an offence if they refuse to answer questions (i.e. there’s no right to remain silent). This includes failure to provide passwords or encryption keys to electronic devices. And hundreds of thousands of innocent people have been subjected to what are known as ‘Schedule 7 stops‘.

The traumatic effect of Schedule 7 was highlighted by journalist and politician David Miranda. A review of Home Office documents by The Canary has shown that over 590,000 people have been ‘examined’ under Schedule 7 from 2009 to 2017, without any suspicion of wrongdoing.

The Terrorism Act 2000 allows a person to be detained under Schedule 8 for up to six hours without charge or suspicion of a crime. And access to a lawyer can be denied.

Displaying an ‘article’ or ‘item of clothing’ “in such a way or in such circumstances as to arouse reasonable suspicion that he is a member or supporter of a proscribed organisation” is also an offence. As is collecting or making:

a record of information of a kind likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism, or … possesses a document or record containing information of that kind

Fighting terrorism or banning resistance?

UK citizen Josh Walker was recently prosecuted for possession of the Anarchist Cookbook (which can be downloaded legally from Amazon) after he returned from volunteering with the YPG in its fight against Daesh. He faced 10 years in prison. A jury later found him not guilty.

Legal scholar Dr Vicki Sentas assessed the effects of banning groups like the PKK in 2014, writing:

Some of these actors have used armed conflict to further political claims for statehood, regional autonomy or ethno-cultural rights and have a broad support base – for example, [the Baluch, Palestinians, Tamils, Basque,] among other peoples.

Some non-state armed groups (and nation states) breach the laws of war by targeting civilians. But listing does nothing to stop the use of terror by either side. The idea is that by criminalising the broadest range of relationships connected to armed conflict, Britain can de-legitimise the organisation and eradicate its support base. What does this look like when the support base for an armed conflict demands recognition of minority cultures and languages, accountability for state crimes and an end to conflict?

Yet the British government is demanding even more powers via the 2018 bill.

“Oppression must be stopped at the beginning”

Thinker and journalist H.L. Mencken once noted:

The trouble with fighting for human freedom is that one spends most of one’s time defending scoundrels.

For it is against scoundrels that oppressive laws are first aimed, and oppression must be stopped at the beginning if it is to be stopped at all.

Those who oppose the further expansion of terrorism powers will have to resist the 2018 bill now before it becomes law. Otherwise, they may one day find causes that they support being criminalised, and without any allies to draw upon.

Disclosure: The author of this article volunteers with the Campaign Against Criminalising Communities.

Get Involved!

– Write to your MP and demand they oppose the 2018 terrorism bill.

– Support independent journalism at The Canary.

– Read about the opposition to anti-democratic terrorism legislation.

– Learn about the campaign to de-list the PKK.

Featured image via Wikimedia and screenshot [pdf]