Note: the author’s partner lives with the disease discussed in this article

Anyone who is chronically ill or disabled may be facing bigger challenges during the coronavirus (Covid-19) lockdown. And there’s one group of people who are more at risk than others. Yet the government is still refusing to acknowledge that these people are extremely vulnerable. One family’s story, however, shows why these millions of missing people are so vulnerable.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis

Myalgic encephalomyelitis, commonly referred to as ME, is a chronic systemic neuroimmune disease. The latest research says it affects at least 65 million people worldwide. Previous research put the figure at around 250,000 people in the UK. But the numbers could be underestimates. Some research suggests 80% of ME cases are undiagnosed. Meanwhile, other studies show a prevalence rate in the population between 0.2% and 3.48%.

While symptoms vary for every person, people living with it often experience:

- A worsening of symptoms brought on by physical activities, mental activities, or both. This is called post-exertional malaise (PEM).

- Flu-like symptoms.

- All-over pain.

- Sleep disturbance / problems.

- Cognitive impairments.

- Impairments of the body’s autonomic systems, such as nervous, digestive, and endocrine.

- Hypersensitivity.

Heightened risk

Only around 6% of people with ME have remission from the disease. But the cause of ME is often clear. Because in around 50% of cases, people get ME following a viral infection. It’s almost as if the virus never leaves them. Some studies have shown people with ME have a constant, increased immune system response. It’s like the person’s body thinks it’s constantly fighting a virus which isn’t there.

So during the coronavirus pandemic, many people living with ME are going to be at heightened risk. Not least because, if they catch the virus, their bodies might again behave like it has never left them. But also because the symptoms of coronavirus may be severely exacerbated for these people.

This is putting a huge strain on people living with ME and their families. So The Canary caught up with one such household to hear how they are coping with the pandemic.

Meet Angus

Tina Rodwell is a campaigner on ME. Her 14-year-old son Angus lives with the disease. And her experience of the pandemic and isolation will probably resonate with many people whose lives have been affected by ME.

Angus is essentially being isolated. As Tina explained, this is because he is at high risk. But the challenge is that the government and NHS won’t recognise him as such. She told The Canary:

He already has undiagnosed and unrecognised damage to his brain that is ongoing. With ME, the medical profession knows and has always known that viruses attack the brain. The neurological disabilities are there for all to see.

People living with ME often struggle to get their illness diagnosed in the first place. But if they do get that, they then struggle further to also get specific complications diagnosed. The neurological impact of the disease is one aspect of this. Yet a lot of research has shown that neurological symptoms are prevalent in ME. It has also shown these symptoms get worse over time. For example, an amalgamation of 10 different studies found that, after one year of having ME, around 38% of patients reported “forgetfulness” as a symptom. After at least 10 years of being ill, meanwhile, around 73% reported the same symptom.

Misunderstood symptoms

Tina continued:

Medical professionals also know that different scans and equipment pick this up. So we should be looking at the effect of the coronavirus, and if encephalitis [inflammation of the brain] is going to be a problem.

Again, research on ME has shown that encephalitis is known to happen. As one paper published on a US government website noted:

It is known that the temporal lobes have a predilection for infection by the herpes virus in acute herpes encephalopathy and encephalitis; therefore, the findings may be related to post-viral mild encephalopathy which could cause the self-reported memory and attention problems.

But one of the biggest challenges for people living with ME is being believed in the first place.

‘All in your head’

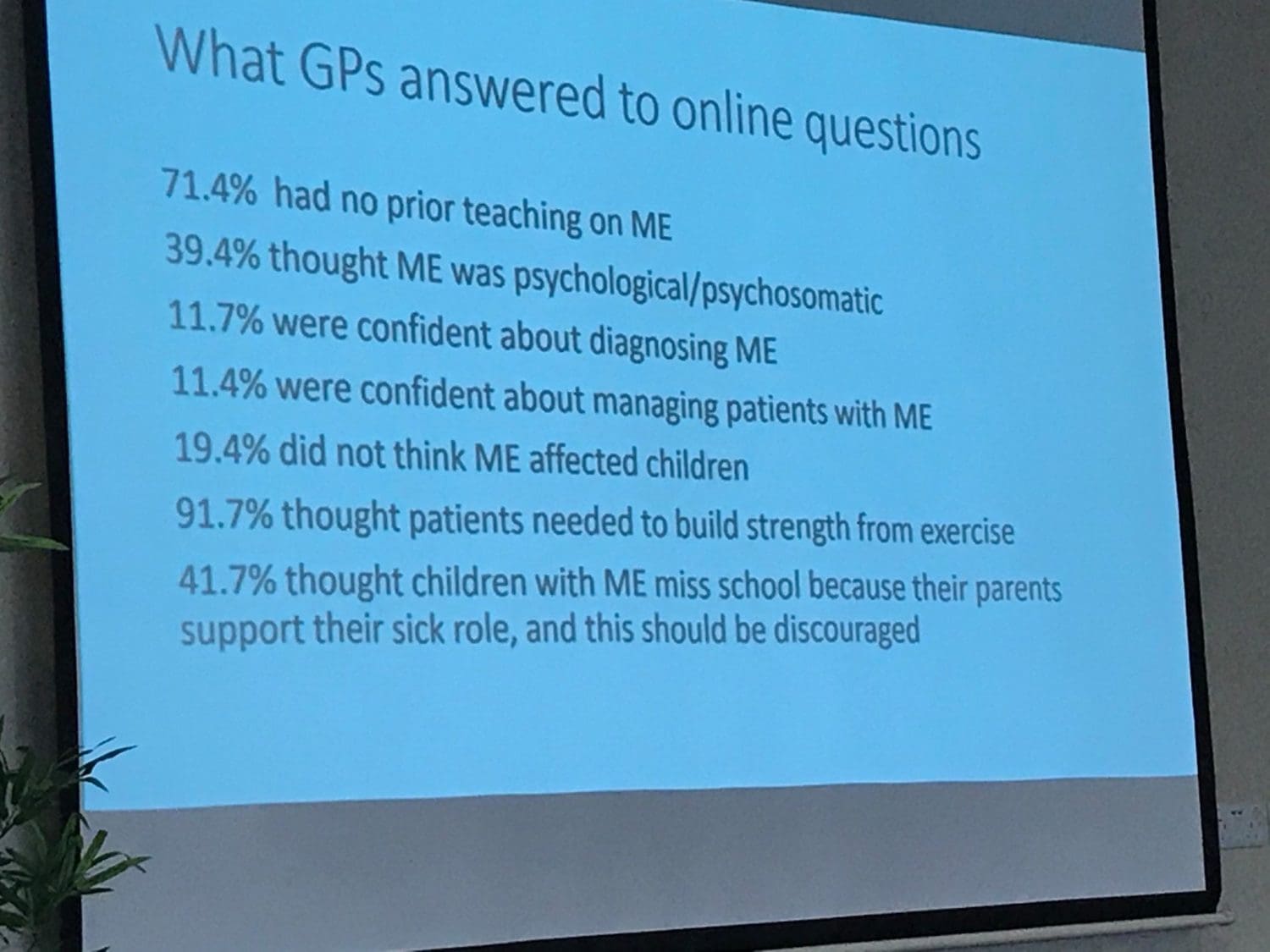

For many years, ME patients have been disbelieved, stigmatised, given incorrect treatment, or told it’s ‘all in their heads’. Because there is still no official cause for ME, and therefore no official treatment, the disease is often viewed as part-psychosomatic. This survey was from a recent conference into ME:

This kind of medical ignorance and lack of understanding has directly impacted Angus. Tina has struggled to get him appropriate medical support, and often finds doctors actually do more harm than good. She told The Canary:

Angus deals with that loathing by doctors every time he becomes worse. We don’t go to the doctors anymore. So now, with coronavirus, imagine how a mother feels: holding a chronically ill child, scared of the potential outcome if he catches it and no reassurance from any medical professional; not for months. While researchers are trying to find a vaccine or treatment, people with ME and their families have been left on their own, essentially in solitary confinement.

If Angus or any other person living with ME catches coronavirus, the outcomes could be horrific.

Catastrophic consequences

As The Canary exclusively revealed, there could be anything up to several million people in the US who potentially could get ME due to coronavirus. But people already living with ME could become even sicker if they catch it. This makes life even more of a constant worry for families like Tina’s.

She told The Canary that, for Angus:

There are many issues with his organs, undiagnosed and unrecognised. This is due to the stupidity of the government and some medical groups listening to the wrong people. ME is not a mental health issue. It is physical and yet psychiatry is trying to take it over. They have no idea of the possible causes, such as autoimmune issues that attack the brain.

So if my son needs to be ventilated or treated in any way, they will be clueless. But more than that, will they ventilate him in the first place? Or will he be left in pain as he always has been? If he gets coronavirus, will, for example, his headaches come back to an extent which he does not know if he will ever be able to endure again? What the hell is the virus going to do him? And what will it take away from him?

Like Angus, many people with ME and their families have countless unanswered questions about the disease. But they also have questions about the impact of coronavirus. Yet it’s being left to a few charities, scientists, and campaigners to try and shed light on the potential impact. So far, the UK government has not recognised the disease as putting people with it at high risk. Nor has any official guidance been issued.

Real-world effects

So currently, all that many people with ME can do is isolate themselves and their families. This is a situation they may well have been in for years before this. As the “Millions Missing” ME Action Network campaign highlights, people living with the disease are often missing from society, trapped in their homes, even their beds – effectively in isolation 24/7/365. This has been the reality for Angus. As Tina told The Canary:

It is one thing to be isolated when the whole world is with you. It’s quite another to be despised for it, when you are completely on your own already.

Angus is hearing and seeing this all around him, too, on social media. I saw him quietly reading about his friend, who is unable to play online due to the zero energy ME leaves you with. He sat there in contemplation, and I thought he was thinking about not being able to play with his friend. But no, not my son. He was feeling useless. And he has been made to feel useless by society.

With the new rules around who is a vulnerable patient, and not helping really ill people, I wonder if they would even bother treating him if he caught coronavirus. My isolated life has many sharp edges to it. But the stark reality is where some people in this pandemic are ‘in it together’, my family are still isolated from them. These people have no idea what ‘isolation’ truly means.

Small changes

But even though Tina and Angus have effectively been isolated from society for years, things have still had to change during the pandemic. As Tina told The Canary:

For me, the change is that my older children are now living with us. One works from home, the other works for our company. The company is a small builders and the deliveries of materials have stopped. So they are completely isolated, too. If we were able to test for the virus, we could organise much better and keep everyone safe. Now, when they come in they strip down and wash, putting clothes in the prepared washing machine. It is organisation and planning that is needed. The other problem is keeping some form of family life going. What do we do?

Torture upon layers of torture

Ultimately, though, the pandemic’s effects on Tina as a mother are perhaps what’s hardest for her to bear. She said:

How do I, as Angus’s mother – someone that has held it together all these years, … keep holding it together when the world is losing direction, and losing understanding of what a virus is capable of? How do I stand alone and keep strong?

Sitting apart from Angus due to the isolation is heartbreaking. I don’t think I have enough words to describe how it feels as a mother. The most important thing in the world to a mother is your family, especially your children and elderly parents. Keeping children healthy, happy and fed is the most basic thing a mother can do. How much longer can I keep that going?

Sadly, Tina’s pain is probably being felt by millions of mothers, fathers, and guardians across the world. ME is a ravaging disease. But what’s more ravaging is the lack of medical knowledge, support, and treatment. So for millions of people around the world, the coronavirus pandemic is just another added layer of fear, worry, and isolation on top of these things already haunting their daily lives. It’s torturous. And it seems, so far, that the UK government is not going to help these people. Therefore, it’s down to the ME community, its advocates, and its supporters to ‘cocoon’ people from the worst effects of this global catastrophe. Because it seems no one else will.

Featured image via Tina Rodwell (used with permission)