This article was updated on 9 October to reflect the fact that the Board of Deputies (BoD) is elected mostly but not exclusively through synagogues. It was also updated to clarify that the BoD sent messages to be read out at synagogues rather than handing out leaflets.

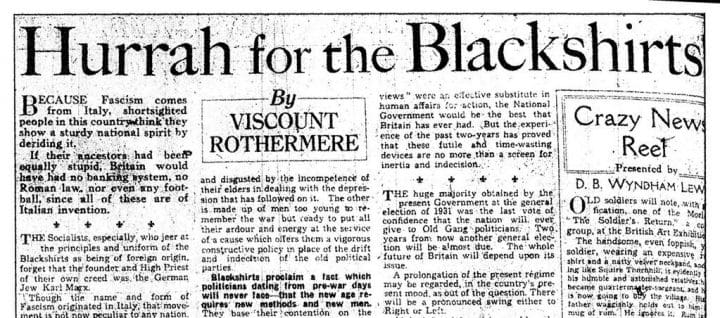

On 4 October 1936, an estimated 250,000 Londoners stood up to the British government and blocked Oswald Mosley’s fascist ‘blackshirts’ from marching through London’s East End.

The epic mobilisation of East End Jews, Irish dockers, and anti-fascists lives on in British memory as the Battle of Cable Street. It’s a shining example of how collective action can defeat the most vicious of racisms.

For the anniversary of Cable Street, The Canary sat down with the seasoned activist and author of Battle for the East End, David Rosenberg. 82 years after the fact, he breaks down the divisions in Britain’s ‘Jewish community’, the Labour antisemitism row, and why, in 2018, the left must learn from their anti-fascist forbearers if they’re going to fight Mosley’s modern day heirs.

Community divides

Today, we remember Cable Street as a coming together of London’s Jewish population and their allies. But as an authority on the history of London’s East End radical history, Rosenberg stresses that in the 1930s, there were deep divides among the community.

And he knows something about division.

He sat with Jeremy Corbyn at the now infamous Jewdas Passover dinner. He’s had several run–ins with the Board of Deputies of British Jews (BoD), and also Stephen Pollard, the editor of the Jewish Chronicle. He’s marched for Palestinians under the banner of the Jewish Socialist Group. The Daily Mail, an early supporter of Mosley’s movement, has smeared him, using his reference to BoD members as “Tory poodles” for ammo.

Today, he regrets his use of words: “I was probably a bit harsh on poodles”.

Returning to the past, Rosenberg traces some of the communal cracks back to the hundreds of thousands of Jews that arrived in Britain after the turn of the 20th century. Most were escaping persecution in eastern Europe.

Gravitating towards London’s East End, many took working class jobs and lived in relative poverty. As fascism was born in Britain, they also had to endure racist attacks at the hands of Mosley’s supporters on a regular basis.

And in the early 30s, there were more and more calls on the UK’s Jewish representative bodies to do something about it.

Heads in the sand

But Rosenberg says that community representatives like the BoD, established in 1760, weren’t keen to call out British antisemitism at first:

The Board of Deputies had this very rosy view of the state and they thought antisemitism can’t really happen here.

They lived in a different world to the people in the East End, and to be honest, they didn’t seem to care for them.

The more well-heeled and conservative section of London’s Jewish community tended to live in London’s West End. Many were already firmly established in British society. They would come to dominate the BoD.

Members were elected – and still are today – mostly through synagogues. According to Rosenberg, the BoD represented religious Jews – the representatives were “often the oldest and most right wing person from the synagogues,”. And there was a lot of hostility to the new arrivals:

They were breaking through the glass ceilings into the establishment and they didn’t want to be saddled with the East European Jewish immigrants and their struggles.

KEEP AWAY

As antisemitic violence skyrocketed, Rosenberg says that lots of East End Jews that had grown distant from the world of the synagogue often felt the BoD didn’t represent their interests. The same was true for the community’s media.

The Jewish Chronicle (JC), founded in 1841, was published in The City rather than the West End, but its editors at the time shared many of the opinions of the BoD. They had similar reservations when reporting on antisemitism and the fascists:

Every time there were reports of an antisemitic incident in the early thirties they’d play it down… and any bad statement by Mosley, they’d say things like “we’re sure that on reflection Sir Oswald will withdraw that.” They gave him a lot of leeway.

In fact, the JC and the BoD often criticised East End Jews for defending themselves. In the mid-thirties, they attempted to tackle rising antisemitism through defamation. But they looked down on direct action against the fascists. Instead, they advised East End Jews to keep their heads down. This was the case in the run-up to Cable Street:

There was a notice in one of the pages of the Jewish Chronicle saying “URGENT WARNING”, “KEEP AWAY”, telling people to stay indoors and saying that any Jew who gets involved is helping the antisemites.

Left-wing turn

The BoD handed out advice with a similar message to be read at synagogues. Rosenberg says both the BoD and JC lost a lot of trust:

When the Board of Deputies did start to finally pay a bit more attention to fascism and got active, most of their activity was to undermine the left-wing Jews.

The response of the self-defined community leaders and newspapers during and after Cable Street led many East End Jews to sympathise more with working class left-wing parties. That included the communists and the leftist Jewish Peoples’ Council (JPC) who led the Cable Street mobilisation, alongside the Independent Labour Party and the Labour League of Youth.

This flourishing of leftist politics among London’s working class Jews would secure the fault-lines within the wider community for years to come.

Right-wing roots

Despite post-war social mobility changing the class structure of British Jewry, some of these fault lines still exist today:

It’s a different context, but there’s a lot of those same political divides, just like in the 30s.”

He adds that especially in recent years:

The bits of the community that are growing are the far-right and the far-left, and it’s the middle that’s collapsing.

For Rosenberg, it’s important to see “the political, economic, cultural diversity” of the estimated 284,000 Jews living in Britain. There’s not just one Jewish community:

People who are on the right talk about the Jewish community as if its some kind of separate entity that’s located somewhere within mainly bourgeoisie society.

Who do they speak for?

Rosenberg references poorer Jews that would benefit from Corbyn’s policies and the falling number of self-identifying zionists in the community. He also describes the resurgence of Jewish left-wing activism since the early 2000s: Jews for Justice for Palestinians, the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions UK, Jewish Voice for Labour, Free Speech on Israel, and Independent Jewish Voices:

So who does the Board of Deputies speak for? It’s the traditional right and further-right. The Board of Deputies has always been the most conservative – with a small c – part of the Jewish community. And to a large extent it’s now a big C.

This is despite the fact that for many years, “a lot of Jews looked on the Tory party as a no-go area,” says Rosenberg:

The current Board of Deputies president [Marie Van Der Zyl] was being interviewed on Israeli television, and she said that the Conservative Party has always been very friendly towards to the Jews. I gave out this huge hollow laugh.

I remember the Conservative party passing the Aliens Act that was keeping Jews out of here. I remember the role of the Conservatives in the 30s and their attitude towards refugees from Nazi Germany.

Coming up to the present day, someone like Michael Howard… when he tried to become a Tory candidate in the 1980s he had to go to 40 different constituencies to find one that would take a Jew. Local Tory parties did not want a Jew as their MP.

Labour antisemitism

And while the BoD regularly attacks Jeremy Corbyn and Labour over antisemitism, for Rosenberg, “they completely ignore the real and verifiable links between the Tory party and antisemites and Islamophobes in Europe.”

He says that it was only under pressure that the BoD made “a very mild criticism of the Tory MEPs lining up to support the antisemitic regime” in Hungary:

The Conservative Party have the most beautiful relationship with those people and the Board of the Deputies won’t say a single word about it unless really, really pushed.

They know that their legitimacy is much more secure under a similar kind of right-wing leadership in society. And I do think a lot of the stuff about Corbyn is nothing to do with Israel/Palestine, it’s simply right vs. left and domestic issues where they would prefer a right wing government.

These people who claim to represent the community are actually representing a much narrower slice of the community.

And according to Rosenberg, the BoD isn’t just turning a blind eye to the Tories:

There’s certainly an element of far-right zionists, who used to be a bit more mainstream, who are now getting into bed with the EDL and Britain First. And the Board of Deputies is incredibly tolerant of them

Lessons to learn

Despite the horrors of WWII, antisemitism in the UK continues to rear its ugly head. Rosenberg is more than aware of the current dangers:

My own view is that although we’ve got this false crisis, this kind of largely concocted crisis around antisemitism in the Labour party, I actually think that antisemitism in society is growing. I’ve seen and heard more antisemitism in the last five years than the previous 55 but its not to do with Israel, it’s just the old prejudices, old stereotypes.

But when people like Margaret Hodge talk about slipping into antisemitism from anti-Zionism as if they’re slipping from the kerb into the road, to me there’s an ocean in between those two positions. You do get people that swim that ocean quickly.

But I think its mainly coming from the far-right. The far-right have flooded the internet with antisemitic stuff and world Jewish conspiracy stuff.

Ghosts of the past

Rosenberg points to the huge numbers at today’s far-right rallies:

People who I know in the anti-facist movement were telling me about that Tommy Robinson march, that every small group that’s existed in the last 20 to 30 years in the furthest bits of the far-right, they were all there in the crowd.

The higher you got in the parties, the more you’d be exposed to the world Jewish conspiracy stuff because it’s still the glue that holds their world view together.

UKIP’s recent push to the far-right is particularly worrying for Rosenberg. He quotes former leader Paul Nuttall regurgitating Oswald Mosley’s slogan “we are now the patriotic party of the working class” on the day of his election in 2016.

Nutall used to be a history lecturer… I don’t think he was ignorant of where that quote came from.

And the party’s recent alliance with the far-right street movement, in particular Gerard Batten’s support for Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, aka Tommy Robinson, is a warning sign:

He’ll talk about shadowy elites who meet in secret, who own the media, and if you’re in the know, you know what he’s talking about.

Stand up, fight back, organise

For Rosenberg, one of the most important things to learn from Cable Street today is the tactics anti-fascists used in the 1930s:

Basically holding placards, calling them racists and fascists and Nazis doesn’t change anyone’s minds.

The people in the thirties recognised that fascism – rather than fascists – was the problem. That fascism was a very anti-working class, racist ideology and it serves capitalism rather than challenges it. And it’s also full of every racist, destructive ideology as well.

But people head in that direction in the absence of alternatives, when they feel very let down by the mainstream politicians

In the thirties, there was a conscious strategy to pull people back, people who were heading towards fascism… to try and engage with them.

He describes efforts by the communists and the JPC to help working class communities organise against cutthroat landlords to bring down rents in the East End. Others would secretly join fascist-majority boxing clubs and try and spread their leftist message at the ringside.

Essentially, to get people on side, you had to show true solidarity and address the real needs of the working class. While much more needs to be done, Rosenberg is very pleased that Corbyn is running a far-reaching Labour Party.

Hope

As the memorial dust settles on Cable Street, the makeup of the East End’s working class – and British society at large – has fundamentally changed. But the spectre of fascism continues to loom.

One of the main lessons we can draw from Rosenberg and the battles of yesteryear is that communities cannot be broken down into simple stereotypes. There will always be communities within communities within communities.

This is the lesson that Oswald Mosley and his fascists learnt to their own detriment in 1936. To underestimate the power of solidarity and diversity is idiocy. To base your entire politics on that principle?

You’ve lost before you’ve even started.

Get Involved!

– Follow the Anti-Fascist Network on Twitter or Facebook for more information about the far right.

– Check out other articles on the far-right by The Canary.

– Read David Rosenberg’s blog or join his East End walking tours.

– Join us, so we can keep bringing you the news that matters.

Featured image via Youtube.

Embedded images via Thomas Wintle, Wikimeda Commons, and Youtube screenshots