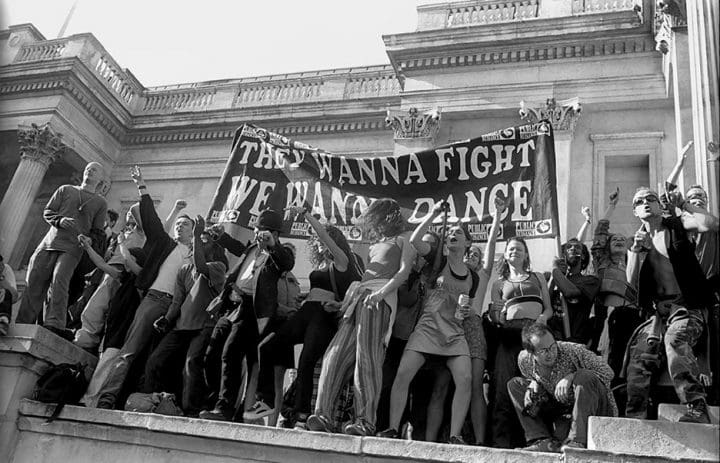

A book called Exist to Resist is a powerful, visual timeline of recent social history. Matthew Smith created a stunning photographic record of activism, underground, DIY and rave culture in the 1990s.

This book is unique: it starts in 1989 and ends in 1997 – the day before Tony Blair’s election. It celebrates the creative resistance and collaborative opposition from an underground revolution that took place, largely, away from cameras. Smith spoke to The Canary about the book and future plans to spread the message of resistance even further.

Underground

Bristol produced at least two great underground artists in the 90s. One hid from the police under trains thinking about how to paint rats quicker. The other spent his time recording the violence the police perpetrated on his friends during the protests at the time.

In 1989, Smith jumped the fence at Glastonbury and started taking photos. This was the first year that a huge police presence was visible inside the festival. It was also the first year that rave culture exploded into the festival in force. And for Smith, it was a turning point, because that year his dad lost their family home following the Thatcher-driven recession.

From 1989 onwards, Smith travelled the UK with his camera and documented the protests, communities and raves that proliferated through the 90s. His work is a direct and creatively political “opposition to mainstream mass media lies about travellers, free parties and festivals”.

A generation had emerged who felt they had nothing to lose. This was a generation who’d had their milk snatched by Thatcher and witnessed parents lose jobs. They grew up under the political iron grip of Thatcher and Reagan. They saw police brutally quash the miners’ strike. And they knew – in the aftermath of events like Chernobyl and Tiananmen Square – that the world was changing irrevocably. This was also a generation who walked headlong into a new era of policing entrenched in the 1994 Criminal Justice Act (CJA).

In documenting this decade, Smith’s book shows exquisitely that art is political and the political is art.

Justice?

The CJA gave police new powers to “remove persons attending or preparing for a rave”. It also, famously, defined raves as “wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”. Gathering with 20 or more friends to dance was now illegal.

But the legislation also took aim at travellers and activists – in particular, hunt saboteurs and anti-road protesters. A new offence of “aggravated trespass” was created that criminalised people taking part in non-violent protest. There were well-founded fears that the act of legitimate protest would be curtailed and criminalised. In 1994, three huge demos took place in opposition to the CJA. As Smith says in the introduction to the book, the CJA:

outlawed travellers, ravers and effective protest, putting in place the rules of a market that would go on to create our modern festival industry.

The CJA was a state-thrown rock, but its ripples failed to quash the spirit of the generation it was meant to contain. It created a tsunami of resistance.

And Smith was there, recording those waves.

Next generation

It’s important to remember that the 90s was a time largely before the internet, mobile phones and the proliferation of people self-documenting their every move. Smith’s black and white images record a decade where the word ‘selfie’ didn’t exist. His book provides a rare and precious visual legacy of an era that went largely undocumented.

But the book doesn’t simply look ‘back’. Whilst it documents the past, it also provides a powerful message for future generations. As Smith told The Canary, the images show:

just how much freedom has been lost in the space of a single generation. While there is still much to celebrate about life and humanity, we want to talk about that issue and look at how it might develop for future generations… our children do not deserve to live with consequences of the failures of the past, so we hope to provoke debate about how we might address and solve the problems that they will inherit over the course of the next generation.

Smith aimed to self-publish the book, so Exist To Resist launched on Kickstarter on Mayday 2017. This was the 23rd anniversary of the first London demo in opposition to the CJA legislation. The crowdfunder raised £23,000 and the book was delivered on election day in 2017. The limited first edition run of 1,100 books sold out without using any traditional retail or distribution networks.

Smith’s now trying to fund the second edition. He’s also formed a collective to get the ethos of Exist to Resist off the page and into the world. A festival of resistance is planned for May 2019.

Another world

Exist to Resist captures a generation who hitched, travelled in trucks, squatted and ate from skips in order to oppose the rise of state-led oppression. They were fuelled by an energy to challenge the state and enact change. For many, ‘community’ was a lived act; not just a word. But this was also a generation who knew how to party – not in pricey clubs but in fields and warehouses across the UK. The aesthetic of the images is as raw and gritty as many of those free parties and protests were.

There was a sense of the ‘real’ in the 90’s that now seems a million miles away – and his aesthetic also captures this perfectly. The book shimmies from police violence to euphoric parties, and the moments Smith captures would simply look odd in false gloss and colour.

Smith’s images capture a world that’s now gone. The neoliberal policies of New Labour and subsequent Conservative-led governments have stripped so much away. As Smith says:

It’s clear that since the 90s the moral integrity of our government has been compromised on an ongoing basis. The social contract is being dismantled piece by piece. Our country is being slowly asset-stripped ready for sale to the highest bidder at the expense of the public.

And he went on to say:

The last recession and the austerity policies that followed can be seen as robbery of epic proportions perpetrated by the very institution that is supposed to govern. Since the digital revolution, much has changed. We live in times where the infrastructure of oppression, inequality and mass surveillance is being constantly upgraded.

Social history

Although Smith’s book might appear to flit from scene to scene – there’s a concrete narrative behind it. Because it documents the unique underground ‘tribes’ that emerged from a perfect storm created by Thatcher’s legacy.

Acid house first drifted to the UK from Chicago in the late 80s. It mixed and morphed to provide the soundtrack for a whole decade, played from DIY sound systems in fields and warehouses across the country. Many pioneers of these parties had been hounded for years by increasingly aggressive cops.

As rents soared and the impact of Thatcher’s right to buy policy took hold, rising numbers of people took to the roads to live in vans and trucks. The brutal police violence in the so-called Battle of the Beanfield in 1985 marked a turning point. It was clear that alternative lifestyles were under attack. But equally, it created an underground social cohesion – to resist, to challenge and yet to keep on dancing in the face of it all.

Free parties were as free as the spirits who danced until sunrise. And the protests that took place alongside them also marked a turning point in social history.

Protest

In 1994, people gathered at Solsbury Hill to protest against the Batheaston bypass. One of Thatcher’s other legacies was a network of new roads, motorways and bypasses. These carved through areas of outstanding natural beauty, and also heralded the systematic decimation of the UK’s public transport system. From Solsbury onwards, camps and communities emerged in opposition to these roads across the UK. Twyford, Wanstonia, Claremont Road, Newbury, Fairmile – and many others – are now tarmac covered place names. But in the 90s they were vibrant communities of resistance that Exist to Resist brings back to life.

Resistance and opposition to the CJA grew through demos, and as it did people also perfected ways to close down entire sections of cities for (now) legendary parties called Reclaim the Streets (RTS). Blending party and protest, RTS was the ‘glue’ that connected the ethos of environmental and anti-policing protests with the sheer exhilaration of dancing to “repetitive beats”.

Causing political mayhem was done with hands in the air, attitude and huge grins. No wonder the police hated and harrassed those involved.

Moments

In 1996, protesters at Fort Trollheim – a camp along the A30 protest – ‘somehow’ arranged for Jimmy Cauty from the KLF to arrive on site with two Saracen tanks. The tanks, known as Advanced Acoustic Armourments (Triple A) were rigged with sound systems. Triple A planned to lock themselves in and play music when the evictions started. This never happened, because police said they had a ‘sonic weapon’.

It’s hard to imagine ‘pranks’ like this happening now without a costly entry fee to a carefully constructed and curated press event. Smith’s images capture a myriad of moments like this, and many others, with casual simplicity.

Exist to Resist presents the interplay of a decade of movements and moments. They were distinct, yet intertwined. Many people moved seamlessly between them. But no one sat down to plan this; it was raw, organically organised across CB radios, word of mouth and phone boxes. The national press failed to really ‘twig’ what was going on until the end of the decade, but Smith was there throughout. What shines through in the images is that Smith is part of this lived culture, not a detached observer.

The revolution will be live…

Beyond a second print run of the book, Smith is planning an event that aims to connect past, present and future. As he told The Canary a “rebel alliance is growing on a daily basis” to:

look back at and celebrate the culture of the 90’s, examine its relevance to right now in the present and also look forward to how the issues that we face right now might develop in the future.

Rooted in the ethos of 90s DIY culture, this project aims to inspire future generations. Smith explained that at a lecture and presentation for students on a “very well respected photography degree course”, he recognised that although many had been to festivals “and a few to free parties… they could not quite believe that in the not too far distant past it was possible to attend such events simply by going”. He said they were stunned that there were no tickets to the ‘events’ caught in Exist to Resist and that people didn’t need:

to provide photographic ID and all your personal details online to attend. That you didn’t need to subject yourself to humiliating and personally intrusive searches from people who could legally steal from you at whim on the way in.

One girl asked Smith, “Why do you think that we don’t have such a culture today?”. As he explained:

that culture and the numbers of people that took part in it represented freedom which has since been criminalised, enclosed and turned into an industry in pursuit of revenue for the state and social control. Almost like a microcosm for society in general.

Lived culture

Whispers of influence from British social documentary photographers like Tish Murtha, Tony Ray-Jones and Chris Killip, whose – often heartbreaking – work pioneered new ways of looking at their own lived culture and experience through the lens, flutter throughout the book. Smith’s work also has echoes of photographers like Nan Goldin because the images display a raw passion and energy that simply can’t be faked.

The spirit lives on…

To a certain extent, the spirit of party and protest Smith captured hasn’t gone anywhere. From the 90s, protests have continued in opposition to globalisation, capitalism and the arms trade. And as technology evolved, so too did the means of organising on a global scale as the Occupy movement demonstrated, taking inspiration from the uprisings of the Arab Spring. But the rise of technology has gone hand in hand with ever-increasing police and state surveillance. In the aftermath of 9/11, too many people have been sold the idea that this is ‘for our own good’.

There’s another big difference – we live in a culture that now tries to package the spirit of resistance as a commodity. As huge festivals charge ever more for tickets, people now pay to be penned in and witness spectacles. The festival of resistance that took place in fields and on the streets has been policed out of (visible) existence.

But its spirit lives on. And in the pages of Smith’s book, it won’t ever go away. As Smith and others move forward with plans for the festival in May 2019, new conversations and collaborations mean this spirit can dance and explode right into a new decade.

Get Involved!

– Follow the next stage of the Exist to Resist journey on Facebook and Kickstarter and view more of Matthew Smith’s work on Instagram.

– Join The Canary, so we can keep holding the powerful to account.

Featured image and all other images by Matthew Smith, used with permission