A Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) minister has gone on record in front of a parliamentary committee to say benefit sanctions work. The overwhelming evidence shows his claims are a nonsense, though. And if you delve deeper into what he said, we can see he was using information from over a decade ago to back up his claims.

Scrutinising the DWP sanctions regime

The Work and Pensions Select Committee is conducting an inquiry into the benefit sanctions regime. The committee says sanctions:

which take the form of docking a portion of benefit payments for a set period of time, can be imposed for breaching benefit conditions like attending a work placement, or for being minutes late for a Job Centre appointment.

Sanctions are applied to Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA), Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), and Universal Credit claimants, among others.

On Wednesday 27 June, minister of state for employment Alok Sharma gave evidence to the committee. Some of it was gob-smacking.

‘We’ve done studies…!’

Sharma claimed that:

We have done evaluation… and what we have seen… is that the vast majority of those, under those regimes, have said that, as a result of sanctions being in place, it’s more likely that they will comply with the requirements…

Labour’s Neil Coyle put it to Sharma that this evidence was “anecdotal”. But Sharma denied this, saying:

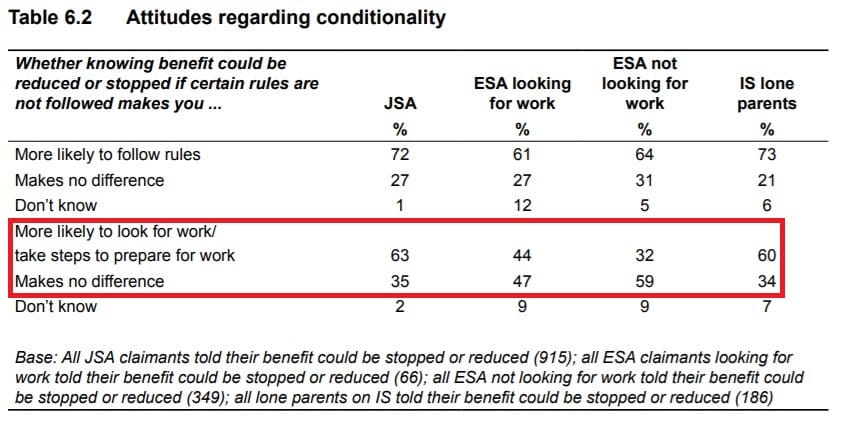

I don’t think it’s anecdotal… The evaluation we’ve done on JSA and ESA showed 70% of JSA and 60% of ESA recipients said that sanctions would make it more likely to comply. 72% of UC [Universal Credit] claimants felt the same way.

Hang on…

The figures Sharma quotes for JSA and ESA are from a November 2013 report, published just 20 months after the DWP made changes [pdf, p5] to the sanctions regime via the Welfare Reform Act 2012. But as the report Sharma quotes from shows [pdf, p157], sanctions didn’t make as many people likely to look for work:

The DWP asking people before they’ve been sanctioned whether it would make them “comply” is, as Coyle put it, anecdotal; even more so when part of the evidence was based on just 66 people’s responses.

Ultimately, Sharma’s claims fly in the face of numerous independent studies and reports – ones that are more recent and comprehensive than the report he quotes from.

The actual evidence…

For example, the National Audit Office (NAO) said in November 2016 that the DWP was “not doing enough” to monitor the effect of sanctions on claimants. It also said the DWP couldn’t quantify the regime’s impact on public finances.

Fast forward to 15 June this year, and the NAO again criticised sanctions – this time in terms of Universal Credit. It noted [pdf, p74] that the rates of DWP sanctions being overturned at appeals suggested “decisions are not always correct”. The DWP’s own data qualifies this.

As The Canary previously reported, between 1 August 2015 and 31 January 2018, 29% of Universal Credit mandatory reconsiderations ended in the sanction decision being overturned. At appeals, this figure was 83%.

In February 2017, parliament’s Public Accounts Committee said [pdf, p5]:

There is an unacceptable amount of unexplained variation in the Department’s use of sanctions, so claimants are being treated differently depending on where they live. The Department has poor data and therefore cannot be confident about what approaches work best, and why, and what is not working. It does not know whether vulnerable people are protected as they are meant to be. Nor can it estimate the wider effects of sanctions on people and their overall cost, or benefit, to government.

More evidence…

In May 2018, the Economic and Social Research Council funded a five-year study on sanctions by six universities. It found that, for disabled and homeless people, lone parents, jobseekers and those on Universal Credit, sanctions invariably did “very little”, were “largely ineffective” or had mixed outcomes. The report specifically noted that the DWP’s “threat of sanction” wasn’t necessary to get people back into work.

The report concluded [pdf, p1] that:

The ethical legitimacy of welfare conditionality… is further undermined by its ineffectiveness in helping people enter and maintain paid work…

Disabled people

Coyle and Conservative MP Heidi Allen asked Sharma whether the DWP had evaluated the effect of sanctions on disabled people, carers, and lone parents since the 2012 reforms. This is because, Allen claimed, these people are “disproportionately” affected by sanctions. But Sharma deflected, saying:

from our perspective, it’s a question of looking at whether or not the sanctions regime overall is working, and we would contend that it is. Because what people have told us is that it does make… it more likely that they will be engaging with the requirements that they’ve got in place. We’re also seeing employment at record levels…

Coyle interrupted, saying:

I think we’re going to have to move on, because I think the answer’s no…

The Economic and Social Research Council’s report said that sanctions for disabled people should be scrapped. It also said that sanctions for lone parents had “little tangible influence” on getting lone parents into employment.

A history lesson

In its written evidence to the committee, the DWP gave no evaluation of the effect of sanctions on disabled people, carers, or lone parents. It did say that:

DWP research shows that mandating claimants to work search review is effective at decreasing time on benefits…

“Mandating claimants” to work search reviews means they will be sanctioned if they don’t complete the review. The source for part of the DWP’s claim was a 2006 DWP report [pdf]. The other source was a 2015 report, which quoted [pdf, p9] evidence on “Jobsearch Reviews” from the same 2006 study [pdf, p9, appendix note 1].

The DWP’s own data on Universal Credit sanctions also shows it doesn’t decrease people’s time on benefits. 66% of people sanctioned stayed on the benefit for 180 days after the DWP imposed it.

The DWP: covering its tracks?

In 2017, a UN committee accused the government and the DWP of creating a “human catastrophe” for disabled people. In summing up, it accused the Conservative government of effectively trying to cover its tracks, through “unanswered questions”, “misused statistics”, and a “smoke screen of statements”.

Sharma was effectively dong the same thing in front of the Work and Pensions Select Committee; using out-of-date information, and deflecting to avoid difficult questions. His evidence shows a department and a government on the run from the truth: largely because they have indeed created a “human catastrophe” in this country.

Get Involved!

– Support DPAC fighting for disabled people’s rights.

Featured image via Parliament TV – screengrab and UK government – Wikimedia