The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is responsible for some truly astounding figures relating to benefit claimants. The stats, analysed by The Canary, show a significant change in the department’s operations over the past decade.

The DWP: a losing streak?

The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) is responsible for publishing the data on benefit appeal outcomes; those which a claimant takes to a tribunal because they disagree with a DWP decision. Appeals could be made, for example, over a sanction or a DWP denial of a benefit claim. As The Canary previously reported, the success rate for claimants when appealing Personal Independence Payments (PIP), for example, was 65% in 2016/17. Now, the Mirror has said that the rate of PIP appeal success has hit an all-time high of 71% for the first quarter of 2018.

But delve deeper into the figures, and a worrying trend appears.

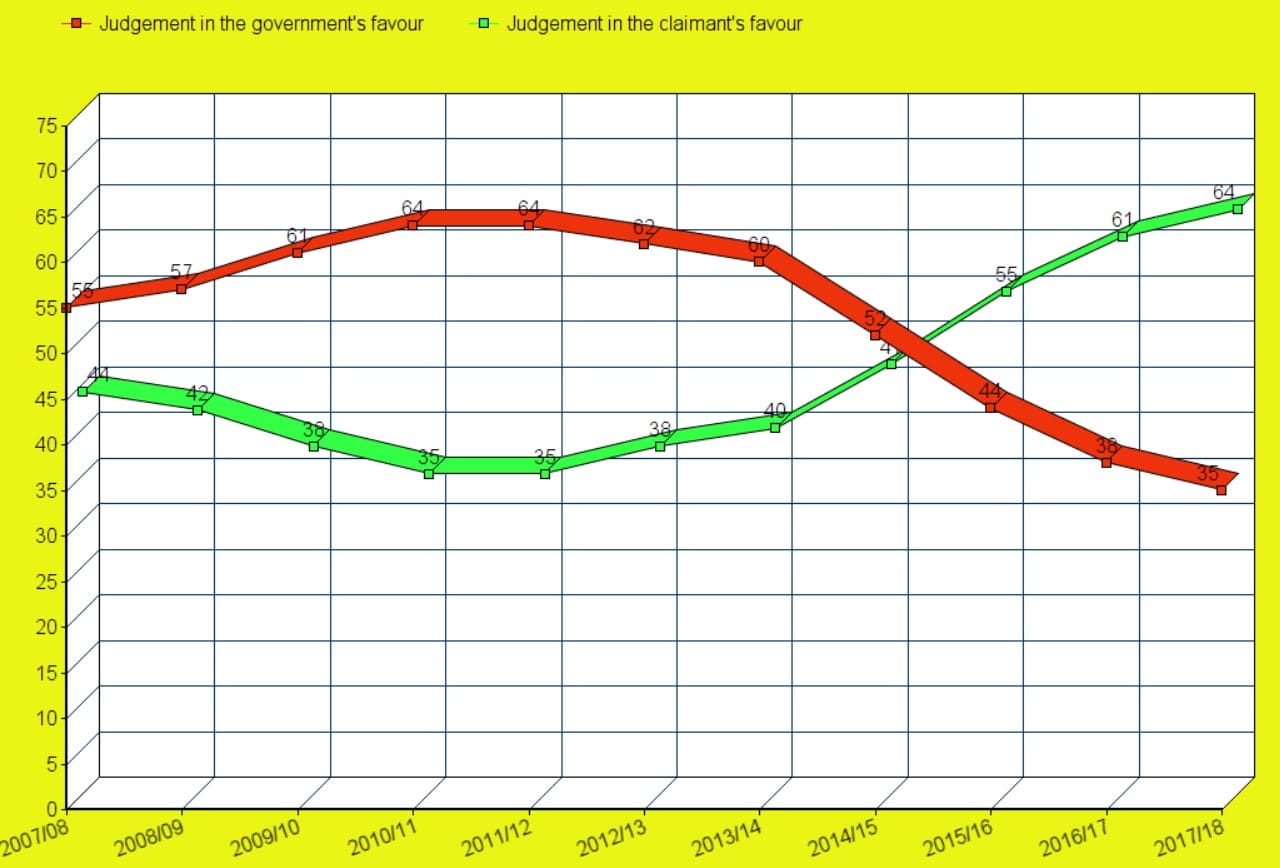

The MoJ releases the appeal data [xls] for all benefits, including one (tax credits) administered by HMRC. It shows the total number of appeals and their outcomes since 2007/08. From 2007/08 to 2013/14, the majority of appeals went in the DWP’s favour. But in 2013/14, this began to change. Now, the majority of appeals go in the claimant’s favour; the graph below shows the percentage of judgments going either way. Note: of the 2.57m appeals since 2007/08 [xls, table SSCS_3, rows 5-43, column D], 1.21% have related to HMRC. These are included in these figures:

Delving deeper

In short, the DWP has gone from winning most appeals to losing them, in the space of around four years.

Looking in detail at the figures, the percentage of appeals going in the DWP’s favour began [xls, table SSCS_3, row 105, column D] to decrease in quarter four of 2011/12. It fell by nine percentage points between quarter four of 2013/14 and quarter four of 2014/15 [xls, table SSCS_3, rows 145/165, column D]. The most recent data for quarter four of 2017/18 (January-March this year) shows that just 33% of appeals were going in the DWP’s favour [xls, table SSCS_3, row 225, column D]. This is from a high of 66% in quarter three of 2010/11 [xls, table SSCS_3, row 80, column D].

The reason for this shift appears obvious.

In 2013/14, PIP began to replace the Disability Living Allowance (DLA), Prior to this, most DLA appeals went in the DWP’s favour [xls, table SSCS_3, column H]. Ever since the DWP introduced PIP, its appeals have always gone in the claimant’s favour, with the exception of the first three quarters [xls, table SSCS_3, column AG].

Also, since quarter one of 2014/15, the majority of Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) appeals have been going in the claimant’s favour [xls, table SSCS_3, row 150, column T]. Meanwhile, although the majority of Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) appeals still go in the DWP’s favour, this dropped from 70% in quarter one of 2014/15 to 53% in quarter two and has never recovered [xls, table SSCS_3, rows 150/155, column AA].

So what changed?

The Welfare Reform Act

In December 2012, the Coalition government and then work and pensions secretary Iain Duncan-Smith introduced a much harsher sanctions regime [pdf, p17-18] for ESA. The change in ESA appeal decision outcomes could be, in part, to do with tribunal judges disagreeing with DWP sanctions. But there’s a piece of legislation which may have had a bigger impact.

The Welfare Reform Act 2012 came into force on 1 April 2013. It made a number of changes, including:

- Introducing the so-called ‘Bedroom Tax’.

- Abolishing crisis loans.

- Introducing the ‘Benefit Cap’.

- Restricting the amount of ESA people could claim [pdf].

All of these measures were financially detrimental to claimants. The act also introduced the JSA “claimant commitment“, slashed Income Support for lone parents and introduced greater DWP powers over benefit fraud. It could be possible that all these regressive measures, coupled with austerity measures impacting on disabled people and lone parents the hardest, are leading tribunal judges to recognise the precarious situation the DWP is leaving people in.

The act also introduced Mandatory Reconsiderations. Previously, if a claimant disagreed with a DWP decision, they would go straight to an appeal tribunal. But now, they have to ask the DWP to reconsider their claims first. But as the Child Poverty Action Group charity said at the time of the act being introduced:

An obvious cause of concern is that many claimants will drop out of the appeal process by having to challenge the same decision twice, or simply get confused or defeated by the bureaucracy…

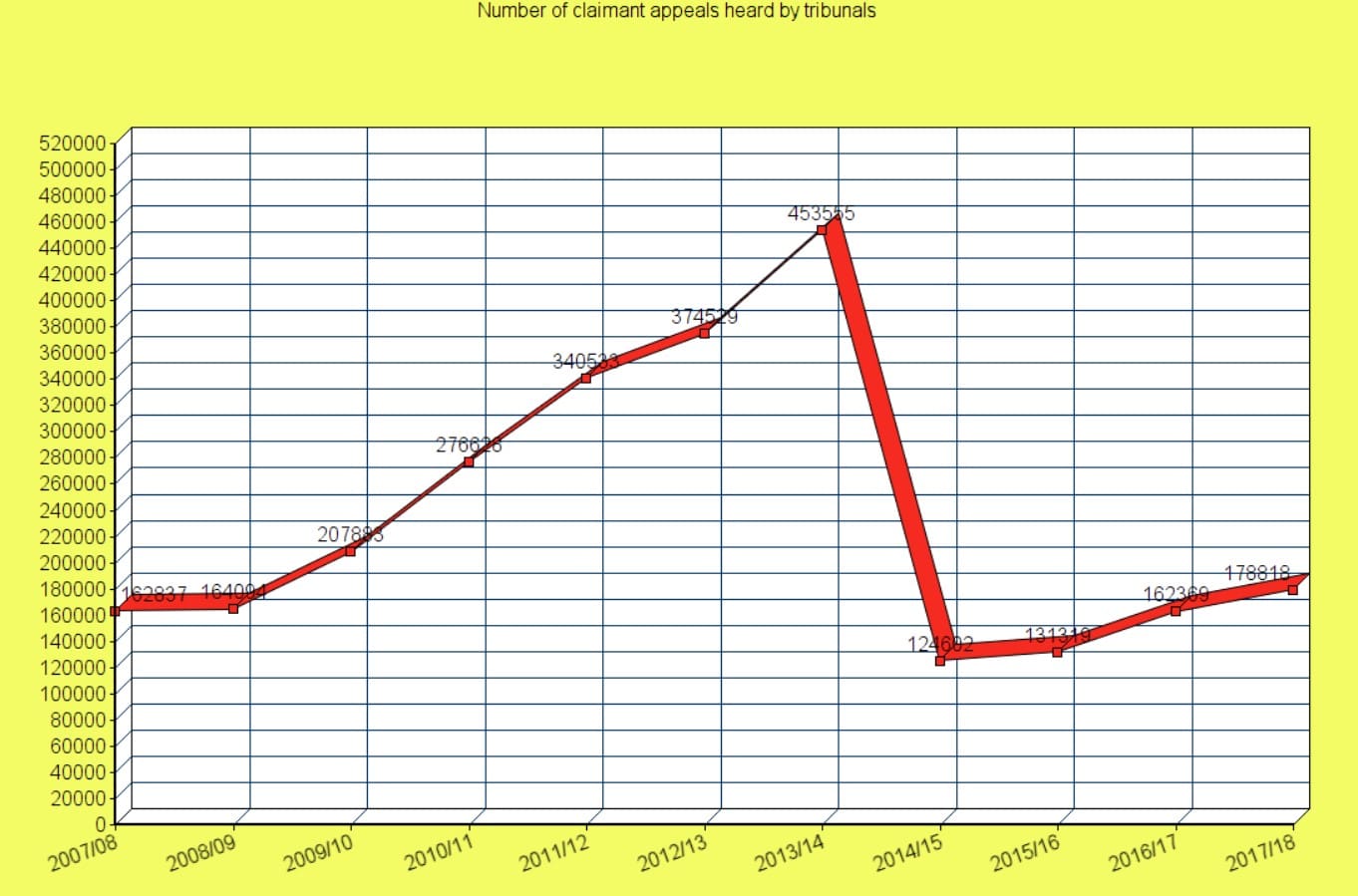

Its concerns seem to have become a reality. Because since 2013/14, the number of overall appeals has sharply dropped:

This doesn’t appear to be due to the DWP awarding Mandatory Reconsiderations in favour of the claimant. For example, as The Canary previously reported, the number of PIP Mandatory Reconsiderations going in the claimant’s favour was 22%.

A flawed department

The Canary asked the DWP for its assessment of why the outcomes of appeals have changed so much. It hadn’t responded by the time of publication. But it previously told The Canary, regarding Mandatory Reconsiderations, appeals and sanctions:

We’re committed to ensuring that people receive the benefits they’re entitled to, but it is reasonable that people have to meet certain requirements in return.

Sanctions are only used in a very small percentage of cases when people fail to meet their agreed commitments to look, or prepare, for work.

When sanction decisions are overturned it’s very often because new evidence is provided during mandatory consideration or appeal.

Overall, the reason for the majority of appeals now going in the claimant’s favour could be a relatively straightforward one. It may simply be down to the fact that tribunal judges have disagreed with the DWP’s harsher treatment of claimants over the past few years, and make judgements accordingly. But what we do know for certain is that, when so many appeals are going in the claimant’s favour, something is seriously broken at the DWP.

Get Involved!

– Support Disabled People Against Cuts and the Mental Health Resistance Network.

Featured image via UK government – Wikimedia