A critically acclaimed play is returning to the London stage for a one-off performance. But far from being about a long-forgotten crisis, its subject matter is completely relevant now. And in some respects, it’s needed more now than when it was first released in 2017.

Food banks. As they are.

Food Bank As It Is, by Tara Osman, will be performed on 5 March at the Chelsea Theatre in south-west London. The play, performed and produced by volunteers, depicts the stories of people using food banks. But it is not a complete work of fiction: Osman was a food bank worker and the stories are based on her experiences on the front line. So, The Canary caught up with Osman to discuss the play, poverty and why the debate about food banks still rages on.

The safety net: eroded

You can read Osman’s full interview here. She says that she was compelled to write Food Bank As It Is after being “pretty disturbed” by what she saw working at a food bank. Initially drafted in as a support worker, she quickly realised that people used food banks as “a direct result” of the government’s welfare “policies and decisions”. She told The Canary, for example, people were there due to:

the use of sanctions, the long delays in receiving payments when switching… benefits… (way before Universal Credit was rolled out), the re-assessment of many Employment and Support Allowance [ESA] claimants, resulting in people’s claims being suspended and their payments being stopped.

I was particularly appalled at the number of children and disabled people we were helping. And I witnessed many people in states of distress, crying and expressing feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, even talking about wanting to kill themselves. I felt as though these stories were not being told and that in general the public had no idea how bad things were and how much the welfare benefits safety net had been eroded.

[We] really wanted to convey… what it is like to hear someone’s story of going without food, to witness her breaking down in tears or to be with him while he eats his first meal in five days. I wanted to bring the food bank to life for those who don’t know what it’s like to be in one with the aim of galvanising audiences to take some kind of action after seeing the play.

A spiralling crisis

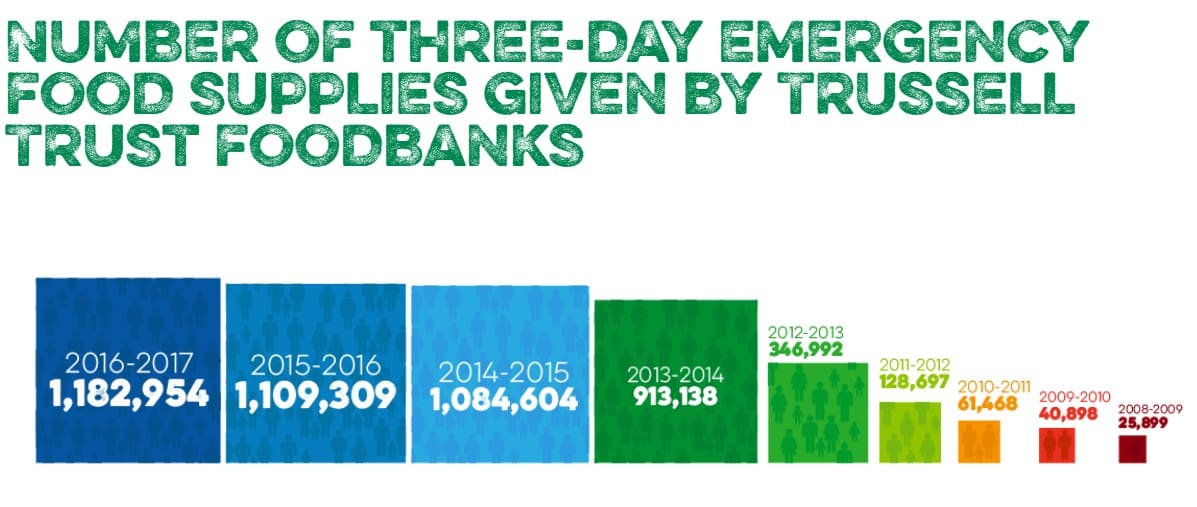

Food bank use in the UK has spiralled to severe levels since 2010. The Trussell Trust, one of the largest food bank networks, reported that between April and September 2017, it gave out 586,907 three day emergency food supplies, a 13% increase on the same period last year. And 208,956 of these parcels were for children. Since 2009/10 the Trussell Trust has seen a surge in demand:

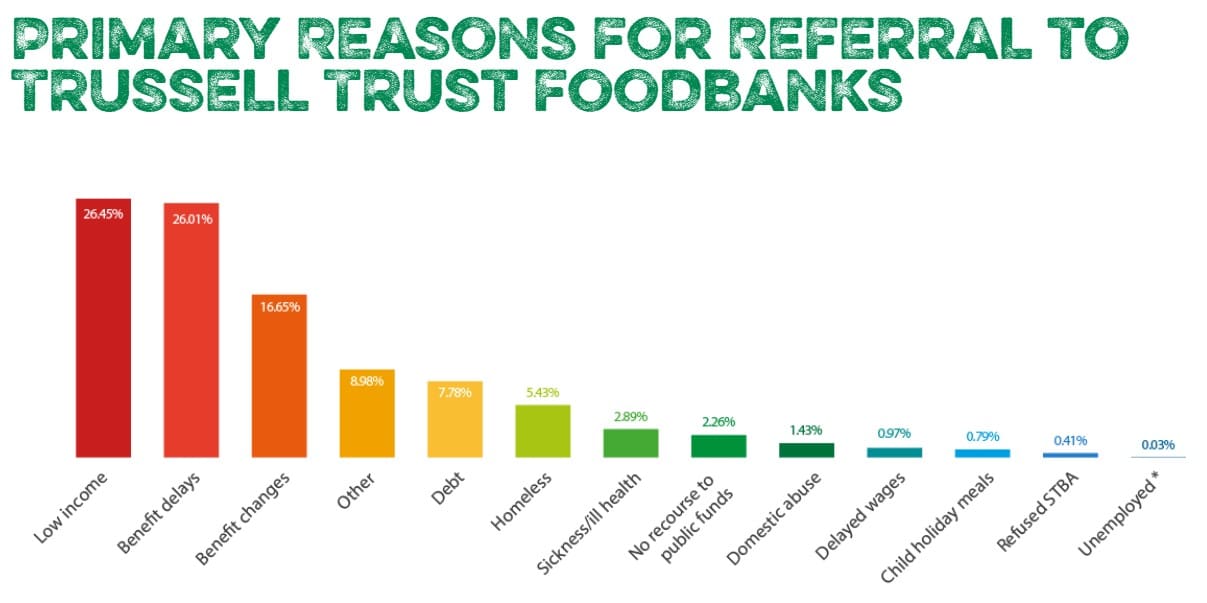

And it appears the reasons Osman cites for people using food banks tie-in with the Trussell Trust’s figures:

But the real figures may be much worse. In 2016, the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Hunger estimated that more than half of the emergency food issued came from organisations outside of the Trussell Trust’s figures.

The government says:

Theresa May says there are “complex reasons” for food bank use. But Osman disagrees with this. She told The Canary:

The rise in food bank use is a very rough and ready indicator of levels of poverty… What we know from research is that people turn to food banks as a last resort and that there are many people who could benefit from food banks but do not use them, either due to lack of awareness or reluctance to use them.

Of course, when any new service is set up and advertises itself, more people will hear about it and more people will refer to it. So, a percentage of the increase in food bank use will be due to increased awareness. This does not mean that demand for food banks is ‘created’ by their very existence, rather that more of the people who are going without adequate food are able to access a food bank.

Real life hardships

Food Bank As It Is recounts the real life stories of people using these services, with a particular focus on the welfare system’s influence. Osman says that her team was drawn to the play for this reason. She praises the team, saying they are all committed to “promoting social change through theatre”. She told The Canary:

There have been times for all of us, I think, when we have been challenged by the work but we have always supported and encouraged each other. Any difficulties that we might experience are nothing relative to the hardships that hundreds of thousands of people up and down the country are facing every day.

And the “hardships” people are facing have become more prominent in the public consciousness. There has been a noticeable rise in media coverage of food banks and their use. But while Osman acknowledges that there is more awareness of food banks’ existence, she feels that “there is still a huge lack of awareness about who they serve, what exactly they do, and what underlying factors drive their use”:

I think people often confuse food banks with soup kitchens and assume that we help mainly homeless people. When I talk with people who are volunteering at the food bank for the first time, they often express surprise at the diversity of our clientele, and it’s true that there is no ‘typical’ person who uses a food bank. Despite this the myth of the ‘scrounger’ still persists, from what I can tell, and is incredibly hurtful for people who use food banks, many of whom talk of the shame of stepping through the food bank door. It’s as though they have internalised the negative view of themselves peddled by certain elements of the press.

The probelm with the media

Osman is also unconvinced that the media always gets the right message across. She said the press usually cite Trussell Trust, while not acknowledging it only makes up two-thirds of UK food banks. And she also gave The Canary an example of the media watering-down the reality of the situation:

One of our clients at the food bank recently gave an interview to a London newspaper. The article was poorly written, in my opinion, and the crucial details of exactly what had happened to bring this client to the food bank were omitted. The comments underneath the online article ranged from supportive to abusive, and I felt that the article had let our client down by not being specific about her situation. For example, it’s not that she was budgeting her money poorly; she actually had no money at all with which to budget, as her husband is too ill to work yet has not been granted ESA, and she herself does not have a work permit for this country. People make all sorts of assumptions about food bank clients and they can only be challenged by accurate and detailed reporting. The reality is that there are often very specific and preventable reasons why people need food banks, and there is well-researched evidence available to the media if they choose to look at it.

Getting involved

Food Bank As It Is successfully shows the despairing reality of an ugly phenomenon in the UK. But what adds to this is Osman and her team giving a question and answer session after every performance. It starts with them asking the audience to provide a one word response to the play, then breaks into a discussion. And Osman believes this is crucial, because she doesn’t want people to just leave:

with a sense of how difficult things are at the moment, but also a sense of what they can do to help. And by help, I mean to help address the issues underlying food bank use and ultimately make food banks a thing of the past.

We need the political will

Food Bank As It Is is a profound example of art meeting politics to produce something that is not only a force for good, but one that aims to promote a paradigm shift in society. And while Osman believes there is no ‘quick fix’ as such to the food bank crisis, she does think there are numerous ways the situation can improve. But ultimately, she says, we need the “political will” to make a lasting change:

We need the political will to come up with an ‘exit plan’ for food bank Britain, and we need food banks to focus their efforts on planning for a future in which they are not needed…

In my view it is crucial that we nip in the bud any further institutionalisation of food banks and in particular that we don’t go down the route trodden in the US where food manufacturers and retailers are intimately involved in the food bank business and food poverty has become something that provides commercial benefits.

But most of all, we need to confront what is happening in the UK head on, look it in the eye and make a decision as a society – do we or do we not think it is OK that so many of our fellow citizens (children as well as adults) are regularly going hungry, sometimes going without food for days? Is this really acceptable? If it’s not then we need to do something about it, and fast.

Get Involved!

– Reserve tickets for Food Bank As It Is on 5 March at the Chelsea Theatre.

Featured image via Paula Peters