According to recently-unearthed documents, people who have participated in a demonstration, are members of a political campaign group, or who have fought the government’s cuts, can become a target of a government programme that monitors ‘extremism’.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg. And it’s more than just democracy at stake.

Widening the net

The Prevent programme was originally designed to combat terrorism. By 2015, Prevent training was made mandatory for public bodies, including schools and the NHS. And within a year, over half a million public sector workers had undergone that training.

More recently, the police have been keen to show that the programme is not discriminatory against the Muslim community. The head of the Met Police’s Counter Terrorism Command Dean Haydon said:

Prevent is not just about the Muslim community. It goes across all communities.

But statistics show the programme is most definitely weighted against the Muslim community.

The evidence

It’s known that police have equated the Occupy movement – which merely sought a more equitable society – and the Greens with extremism. And now, thanks to a recently published document, we know more clearly what Haydon means by “all communities”.

In 2016 a Prevent Counter Terrorism Local Profiles (CTLP) questionnaire [pdf] sought intelligence on individuals involved in a range of political activities. These included anti-fracking, anti-war and anti-austerity protests.

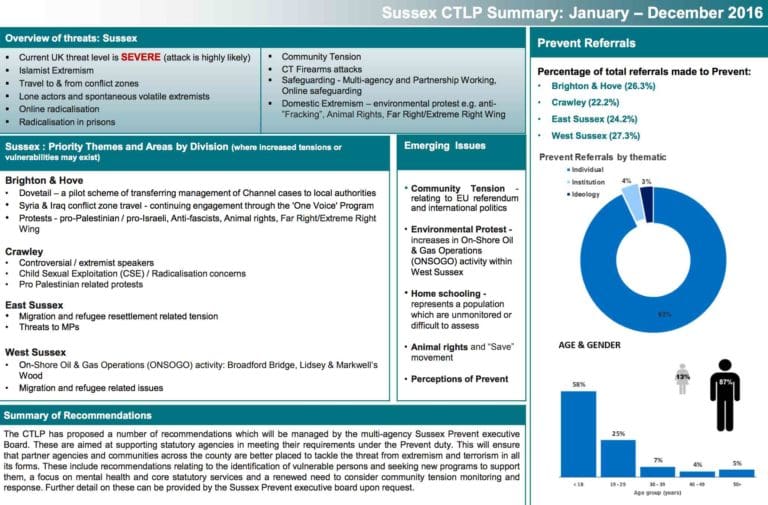

This document, however, wasn’t a one-off. A Sussex CTLP document (sourced by Cage) specifically identified anti-fracking protests too, as well as anti-fascists and even people who choose to home educate their children:

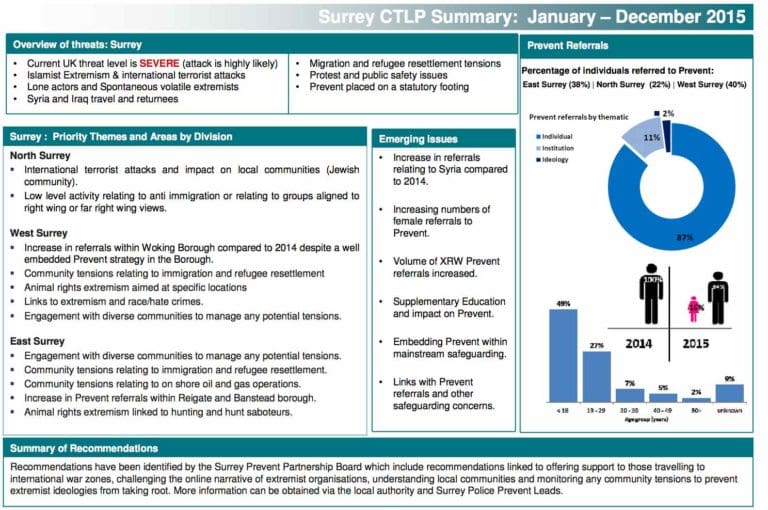

A Surrey CTLP document (also sourced by Cage) covers some similar ground:

And The Liverpool Echo exposed more documents that classed [pdf, p2] anti-fracking campaigners alongside terrorist groups.

The wider context

Via the Prevent programme, political policing has expanded into most sectors of British society. And it’s deploying a vast army of amateur snoopers, who could easily make poor judgements, record intelligence incorrectly and pass on biased information.

Intelligence-gathering, however, is not just the preserve of Prevent. For decades Special Branch, or units such as the Special Demonstration Squad, gathered intelligence on political dissent and activists. And in more recent years undercover policing has been hit by scandals. In particular, undercover police officers formed illicit relationships with activists to infiltrate political groups.

Meanwhile, armed with new snooping powers and technologies, the authorities have now adopted other approaches. This includes mass surveillance by the security services and data-matching by multiple agencies. A redacted National Police Chiefs Council document [pdf] also outlines the importance of social media as a source for intelligence-gathering.

Furthermore, the demise of private blacklisting agencies such as The Consulting Association and its predecessor the Economic League left a gap in the vetting ‘market’ that state agencies, the high street and specialist employment bureaus could fill.

Threat to democracy

Prevent critics include the UN Human Rights Council, Liberty, the National Union of Teachers and more than 150 higher education academics.

And perhaps it is ironic that the Prevent programme, which claims to protect democracy, may prove – with the assistance of mass surveillance technologies – to be one of the biggest threats to democracy since the state’s assault on Chartism.

In 1819, a rally of 60,000 Chartists protested poverty and lack of democracy. At the rally, dragoons acting on state orders hacked or trampled to death an estimated 18 people, including a child. And nearly 700 men, women and children sustained serious injuries. On hearing of that dreadful event – subsequently known as the Peterloo Massacre – PB Shelley wrote the epic poem The Masque of Anarchy. It ends in these famous lines:

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number-

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you

Ye are many – they are few.

Earlier this year, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn revisited those lines at the end of a stirring speech he gave at the Glastonbury music festival. Although the authorities banned Shelley’s poem for many years, today we can all read or hear it. But can we act on its message?

Perhaps so, as we are the many.

Get Involved!

– Check out Together Against Prevent and PreventWatch.

– Read other articles in The Canary on the Prevent programme and blacklisting.

Featured image via Pete Birkinshaw/Flickr