After Jeremy Corbyn ordered Labour MPs to vote in favour of triggering Article 50, the resignations began. And while chaos arose in Camp Corbyn, it provided the Conservatives the perfect opportunity to admit they had broken yet another promise to the people.

This time, it was down to International Trade Secretary Liam Fox. Despite grand promises and ambitions, it turns out the government won’t be able to fulfil its trade targets. As such, it will not be meeting its target of doubling UK exports to £1tn by 2020.

Export target

On 1 February, Fox blamed a slow down in global trade. He admitted to a parliamentary inquiry:

I think it’s unlikely to be achievable by 2020. I think it’s an achievable target in the years thereafter

His announcement came just before the release of the Brexit white paper, which revealed the government’s ‘plan’ [pdf] and priorities for Brexit.

The £1tn target was set by former Chancellor George Osborne in his 2012 Budget speech. It was also outlined in the ‘2020 Export Drive’. It states:

But the aspiration to export £1 trillion of goods and services by 2020 also requires a bolder, more ambitious, focused and collaborative approach from Government and our partners in business and industry, ensuring we are united in taking every opportunity to support UK exporters.

After the target was set, several MPs spoke out claiming it was unattainable. In 2016, former Minister of State for Trade and Investment Lord Maude reiterated that the government’s plan to double UK exports to £1tn by 2020 was a “big stretch”.

The plan

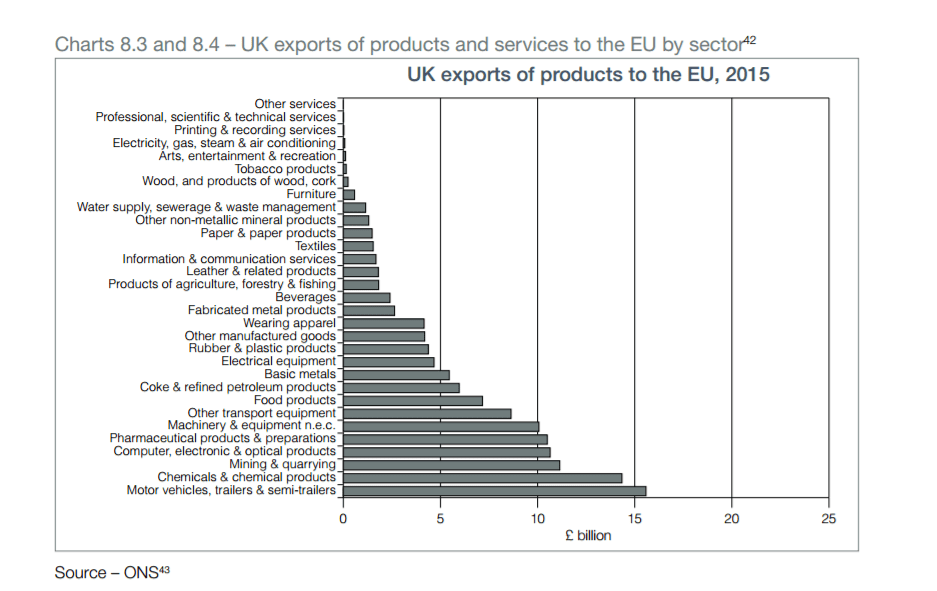

The fact that the government cannot fulfil Osborne’s exaggerated targets comes as no surprise. This chart, taken from the Brexit white paper [pdf p38], shows what the UK exported to the EU in 2015:

The paper [pdf p37] states:

The UK exports a wide range of products and services to the EU. For example, exports of motor vehicles, chemicals and chemical products, financial services and other business services all account for significant shares of total UK exports to the EU.

As the chart shows, the UK’s major exporting industries are: motor vehicles, chemicals, mining and quarrying, and electronics. Almost entirely private sector.

Automotive industry

Eight of the world’s biggest premium car manufacturers manufacture in the UK. This includes Aston Martin, Rolls-Royce, and Jaguar Land Rover [pdf p14]. As well as this, the UK is a hub for the production of commercial vehicles like buses, coaches, and cars.

According to the motor industry trade body, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), it’s an industry that employs around 814,000 [pdf p8] and adds £18.9bn in value to the UK economy.

But while car manufacturing is currently booming in the UK, with more than 1.72 million vehicles built in 2016, its future is uncertain.

Despite some like Rolls-Royce pledging their allegiance to the UK, others (including Nissan) have spoken out about their concerns over Brexit and whether they have a future in the UK. SMMT also predicted a decline in car sales in 2017 and stated automotive companies would be less likely to invest in the UK because of Brexit.

Due to its dependence on the private sector, the UK would be hit hard if such companies removed their investment.

Mining

Likewise, mining is an entirely privatised sector. Glencore is the biggest mining and commodity trading company operating in the UK. In 2012, it generated $236bn/£189bn in revenue from its global operations. While the company’s headquarters are based in Switzerland, it also has a registered office in Jersey. Both are tax havens.

In 2015, Glencore faced a horrific year for trading due to a fall in commodity prices. In four months, its share value decreased by 43.4%. This wiped £17.75bn off the overall share value.

The World Bank has predicted strong gains for industrial commodities in 2017. Yet despite showing strong signs of recovery, the industry is still a volatile one. The collapse of the UK steel industry is an example of this.

One of Glencore’s key markets in the UK is North Sea oil. But according to recent research, demand for coal and oil will decrease from 2020 onwards because of the shift to renewable energies and technologies. If this happens, Glencore and other key companies in this sector could remove their investment and pull out of the UK.

Worrying market

What’s equally troubling is that the UK is reliant on imports to survive. It doesn’t produce enough to sustain its population.

As the report states [pdf p 37]:

The UK is a major export market for important sectors of the EU economy, including in manufactured and other goods, such as automotives, energy, food and drink, chemicals, pharmaceuticals and agriculture.

In 2014, the UK was the 12th most dependent on foreign sources of energy out of 28 EU countries. Likewise, the UK imports over 50% of its food and feed from the EU, South America, and Asia.

So not only do we not produce enough of anything to sustain the population, we’re also relying on private profit-driven companies to support our export market.

Fox’s announcement won’t come as a surprise to most. But it highlights how concerning our current trade system is. With so much privatisation, the UK is reliant on factors beyond its control. While we may be a key player right now, if these private companies decide to pull their investment, and the UK doesn’t adapt quickly, it will struggle to survive.

Get Involved!

– Read more about Liam Fox from The Canary.

– Visit our Facebook and Twitter pages for more independent coverage.

Featured image via Creative Commons / Flickr