The death of 10-year-old Robbie Powell on the 17 April 1990 is a case which is still under scrutiny to this day. In what was deemed a preventable death, the little boy died after numerous visits from medical professionals, who all missed opportunities to save his life. His father is currently in the process of getting a legal review of the case from the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). But, as history has shown, the conduct of medical professionals was, at best, grossly negligent.

Note: All evidence cited in this article has been seen by The Canary.

An unnecessary death

Robbie was suffering from Addison’s disease, a serious but treatable condition. But numerous chances to diagnose and then save his life were missed. After two weeks of illness, he died in Morriston Hospital, Swansea, just hours after his parents were refused an ambulance to take him there. Addison’s disease didn’t kill him; the severe dehydration that it causes resulted in a massive drop in Robbie’s blood pressure, causing two heart attacks. The second one was fatal.

As The Canary previously documented, when Robbie was admitted to hospital on 5 December 1989, he was suspected of having Addison’s disease, and the test to confirm this was ordered but not carried out. His parents weren’t told this, but Ystradgynlais Health Centre, a practice of seven GPs where Robbie was a patient, was. The GPs were instructed to refer Robbie back to hospital immediately if the child became unwell again. When Robbie fell ill again, he was repeatedly seen by various GPs, right up until his death. Altogether, his GPs had seven opportunities – and the hospital two – to save Robbie’s life, and all of them were missed.

An independent criminal investigation between 2000 and 2002, found that four of the doctors were grossly negligent, two of them and a secretary had committed forgery of medical records, and the same three had attempted to pervert the course of justice. But an inquest jury in 2004 returned a verdict of death by natural causes, aggravated by neglect. So far, no one has been prosecuted over Robbie’s death.

And at the heart of this story are multiple, repeated failings. Firstly, as The Canary previously documented, by the CPS; but crucially, by the medical professionals who were responsible for Robbie’s care.

Staggering incompetence?

In the final 15 days before Robbie died, he was seen by five different doctors, seven times, four of whom were found by a medical expert to have been grossly negligent. Dr Paul Boladz saw Robbie two days before his death. He refused to visit Robbie at home, and diagnosed glandular fever when he examined him at the local hospital. Robbie was so weak that he had to be carried into and out of the consultation. Boladz prescribed Amoxicillin (which should not be given to suspected glandular fever patients), and booked blood tests for Robbie for two days later. Boladz was deemed grossly negligent.

Dr Keith Hughes saw Robbie the day before he died. He failed to spot the symptoms of Addison’s disease, postponed a vital blood test, was unable to carry out a crucial blood sugar test, due to out-of-date equipment, and initially refused Robbie a hospital admission. Robbie, at this stage, had sunken eyes and was severely dehydrated. Hughes was deemed grossly negligent.

But it was two doctors in particular whose actions were most worrying: Dr Nicola Flower and Dr Michael Williams.

Williams was aware of suspected Addison’s, and saw Robbie six days before his death, when he was seriously ill. He was the only GP to read Robbie’s medical records, and informed the Powells that he would make a hospital referral. He sent the family home, with the knowledge that Robbie could suffer an Addisonian crisis and die, which was the end result. But Williams didn’t action the referral until after Robbie had died. Williams was deemed grossly negligent, and found to have committed forgery of medical records and perverted the course of justice.

Flower saw the young boy twice at his house on the day of his death. In the first instance, at 3.30pm, she refused a hospital admission and stated that the suspected glandular fever had moved to Robbie’s chest. On her second visit at 5.30pm, she said he could be admitted to hospital, but refused to call an ambulance. It was discovered that, 56 days after his death, Flower rewrote Robbie’s medical records to make out that he was well on the day of his death. She was deemed grossly negligent, and found to have committed forgery of medical records and perverted the course of justice.

An unreliable expert?

Professor Ieuan Hughes was brought in by Dyfed Powys police to review the conduct of the medical professionals involved in Robbie’s care. Hughes submitted a report for the CPS investigation into Robbie’s death on 24 October 2002. The detailed report lays out the case against the medical professionals involved in Robbie’s care, set against the standard of one doctor. In it, he confirmed that in his opinion the four GPs were all ‘grossly negligent’ in their care of the young boy. Boladz, Flower, and Keith Hughes all failed to admit Robbie to hospital, even though he would have been extremely ill when examined by them. On each occasion, his life could have been saved. Williams failed to admit Robbie to hospital, as per instructions in his medical records; again the boy could have been saved.

He also laid out two timelines, in relation to Robbie’s death; reconstructing the time course of the Addison’s disease up until 18 January 1990, and then from 19 January to 17 April. But at the actual inquest hearing in 2004, he backtracked. He claimed, under oath, that he could not extrapolate (estimate how the Addison’s developed) relating to the days leading up to Robbie’s death. Either Hughes was not in a position to extrapolate with regards to Robbie’s condition leading up to his death, meaning he should not have mentioned this in his formal CPS report, or he committed perjury at Robbie’s inquest, by retracting his previous official opinion. If the latter is true, it meant that three doctors may have got away with gross negligence.

The General Medical Council (GMC): not fit for purpose?

During an independent investigation called Operation Radiance, the officer in charge, DCI Poole had placed the GMC on notice of Robbie’s case and told them there would be a formal referral of the doctor’s involved, if no prosecutions took place. The two senior CPS prosecutors involved in Robbie’s case and two police representatives met the GMC on 10 March 2003 to make the formal referral. But Poole was excluded from this meeting, even though he was the one who initially put the GMC on formal notice.

A decision was made by the police and CPS not to make the formal referral. Mr Powell was advised by the police and CPS to make a formal complaint against the doctors, which he did in June 2003. Neither the police nor the CPS informed Powell of their knowledge that the GMC had covertly introduced the ‘five year rule’ just four months earlier, which effectively meant that Powell’s complaint was likely to fail. The police and the CPS had overcome this time limit as a consequence of Poole putting the GMC on notice of the complaint two years before the time limit was introduced. Finally, in May 2008, after five years, the GMC rejected Mr Powell’s complaint. Fitness to Practice rules state that:

No allegation shall proceed further, if at the time it is first made or first comes to the attention of the General Council, more than five-years have elapsed since the most recent events giving rise to the allegation, unless the Registrar considers that it is in the public interest, in the exceptional circumstances of the case, for it to proceed.

These rules were made public in 2004 but had actually been introduced in an amendment to the Medical Act 1983 in November 2002. The police and the CPS took the decision not to refer the doctors to the GMC, in the knowledge that the five-year rule could be used against Mr Powell. But Powell was not aware, and had even been informed in writing by the GMC several times there was no time limit. It has been subsequently admitted by the GMC, in a letter to the First Minister of Wales, that they should have informed both Poole and Powell about the rule. But what remains unanswered is why the formal referral by the CPS did not go ahead in March 2003, after the decision was made not to prosecute the doctors when there was sufficient evidence to do so.

Unanswered questions

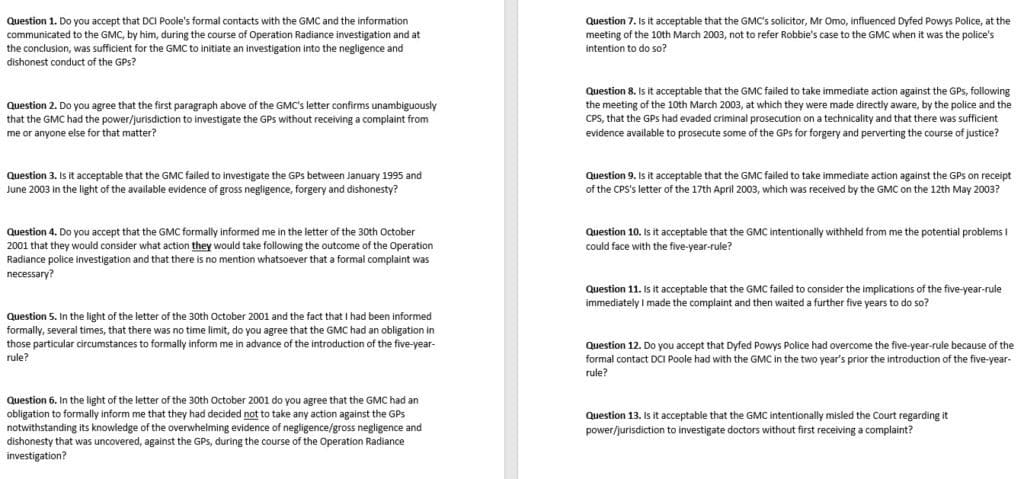

To this day, Mr Powell still has many unanswered questions surrounding the conduct of the professionals involved in Robbie’s death and the GMC. He was in contact with the Chief Executive of the Council for Healthcare Regulatory Excellence, now the Professional Standards Authority, the regulator of the GMC, in 2012, where he laid out 13 unanswered questions relating to Robbie’s death:

Test cases

There are numerous examples of medical professionals being successfully prosecuted for both gross negligence manslaughter and perverting the course of justice, which throw the decisions made in Robbie’s case into a different light.

In Wales, in 1994, Dr Arun Sinha was convicted for perverting the course of justice, in relation to Sallyanne Camp-Richards, 30, an asthma sufferer, after he gave her the incorrect medication that led to her death. He prescribed a beta blocker that is potentially fatal to asthma sufferers. She died of an asthma attack triggered by the drug. While he was charged with manslaughter, the conviction was due to Sinha changing Camp-Richard’s medical records to disguise his mistake.

In Birmingham, in 1997, Dr Salim Najada was convicted for the manslaughter of Peter Coles, 28, after he failed to diagnose that he had developed diabetes. Coles slipped into a diabetic coma on 6 December 1992. Najada was jailed for a year after he failed three times to diagnose Coles’ fatal diabetes. Furthermore, he was also convicted of perverting the course of justice by changing the father of two’s medical records to rid himself of any blame over the death.

Mr Powell brought these two cases to the attention of the CPS in the mid-1990s during the initial investigation by Dyfed Powys police. But the CPS claimed that both cases had no relevance whatsoever to the circumstances of Robbie’s death.

In Leicester, in December 2015, Dr Bawa-Garba and a Nurse, Isabel Amaro, were found guilty of the manslaughter of eight-year-old Jack Adcock by gross negligence. They had both failed to provide Adcock with appropriate care in the last day of his life. Each received a suspended sentence.

In Suffolk, in August 2016, optometrist Honey Rose was given a suspended sentence for the gross negligence manslaughter of eight-year-old Vincent Barker. Rose had failed, five months earlier, to detect the swelling of Barker’s optic nerve and should have urgently referred him for specialised care that would have saved his life. The judge took into consideration that Vincent’s parents did not want for Rose to be imprisoned, due to the fact she had children.

It is difficult to comprehend, in light of the above cases, how the doctors involved in Robbie’s grossly negligent death have evaded prosecution.

To say that there have been numerous failings by the medical professionals who were involved in Robbie’s care may be an understatement. But what is more concerning, is how, over the passage of time, the charges levelled against them have seemingly been watered down, to the extent where no one is accountable. From four accusations of gross negligence, three of forgery and three of perverting the course of justice – to nothing.

Mr Powell, during the course of Operation Radiance, said that he didn’t wish to see Dr Flower go to prison, owing to her four children. But unlike the case of Vincent Barker, Powell’s genuine concern for Flower’s children was used against him as one of the reasons not to prosecute her. And while prosecutions cannot bring back Robbie Powell, if medical professionals have failed in their duty, then someone has to answer.

The Canary will continue working with the Powell family on the investigation into Robbie’s tragic death. You can read the rest of the series of articles, here.

Get Involved

– Read more on Robbie’s tragic story.

– Write to your MP, asking them to intervene in the case.

– Support the family on Facebook.

Featured image via the Powell family