The Conservatives have been accused of failing to deliver on their plans to address the UK’s obesity ‘crisis’. But the government and experts alike fail to acknowledge one important issue: the direct links between obesity and poverty. Theresa May has been accused of putting food and drink companies’ profits over people. Groups like lone parents are working more than ever before. And with poverty forecast to rocket, the situation is only going to get worse.

Half-hearted measures

On 18 August, the Department of Health published the childhood obesity strategy. Originally launched by David Cameron, it aims to tackle the growing crisis early on. Measures include promoting exercise in schools, making healthy food an option in public sector outlets and asking companies to remove 20% of the sugar in their products.

The initiatives surrounding exercise and schools have been welcomed by campaigners. But May has come under fire over food industry regulations. Public Health England recommended two standards be included: reducing the advertising of unhealthy food and ending its promotion in supermarkets, restaurants etc. But the strategy includes neither of these.

Apart from the ‘Sugar Tax‘ which is being introduced in 2018, all of the measures introduced surrounding food sugar content are voluntary. The food and drink industry is just being ‘encouraged’ to act.

But the government and professionals are also failing to address statistics which show a direct link between poverty and obesity. And this may be the root cause of the so-called ‘crisis’.

The poverty factor in obesity

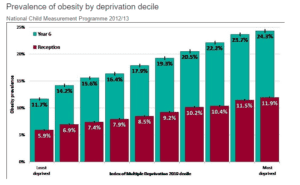

Analysis from Public Health England shows that children living in the most deprived 10% of communities are twice as likely to be obese. This is compared to children living in the least deprived 10% of the country. The areas where children are the most likely to be obese are in the bottom 5% of deprivation:

World Health Organisation (WHO) research from 2010 shows children’s fizzy drink consumption in the UK fell when affluence rose. The same was found for those missing breakfast and not eating fruit. These are two of the biggest influencers of obesity.

These trends are also seen among adults. Levels of obesity increase as wages fall, as education levels drop, and as class status lowers. Also, rates of obesity are highest in women who work in unskilled manual jobs, which is higher than the rate among unskilled men by more than 10%.

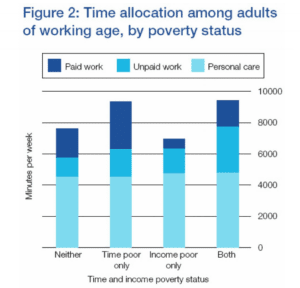

‘Time Poverty‘ is also a related factor. That is, having to work (paid or unpaid) for very long hours.

Research shows that 7% of children live in households that are both in financial poverty and ‘time poverty’, with a third of adults in these households being in full time work. Also, adults who are both time and income poor have the least leisure time:

The UK’s diet has seemingly reacted to this. Sales of ready meals have increased by 50% since 2007. The British Medical Journal found that out of 100 ready meals tested, not one complied with WHO nutritional standards. Research also indicates that cooking skills are lowest among the youngest and most deprived citizens. Combine all of this with employment statistics, and data shows that 6.2% more women with dependent children are working compared to 1996. With men, the increase is 4.3%. And lone parent employment has risen by 20%.

Research is always open to interpretation. Factors surrounding time, money, education and employment may all relate to levels of obesity. But poverty, for whatever reason, is a big influencing factor.

Lots of sugar in your tea

Ethnographer Lisa McKenzie discusses poverty and its effects at length in her book Getting By. In it, she argues that, “through the inequalities that thrive in British society”, living in a deprived area is made even harder. Note the rise of ‘reality porn‘ and stigmatisation from politicians over ‘spongers‘ and ‘scroungers‘.

Anyone who has lived in deprivation will understand. Stigma can lead to low self-esteem and exclusion. But as McKenzie recognises, living in a deprived community also offers its own protections from these feelings. Communities create their own sets of values. Others view eating takeaways, smoking, and wearing ‘bling’ as negative stereotypes of poor citizens (both in and out of work). But in deprived communities, these things hold value.

When you don’t have much, the smaller things take on more worth. Having a takeaway. Taking a bottle of Coke to school like everyone else. Drinking alcohol. These all hold value in deprived communities. But they also make life that bit more tolerable. George Orwell summed this up nearly 80 years ago. In The Road to Wigan Pier, he said:

The ordinary human being would sooner starve than live on brown bread and raw carrots. When you are unemployed, which is to say you are underfed, harassed, bored and miserable, you don’t want to eat dull, wholesome food. You want something a bit ‘tasty’.

And as McKenzie put it last year:

You don’t want to live in absolute hardship with no comfort. Struggling to make ends meet is a misery, and, as Orwell surmised, lots of sugar in your tea … goes some way to relieving, even if just for a minute, the endless misery.

2.6 million more children are set to be in poverty by 2020. The apparent links between obesity and deprivation are only going to get worse. And while measures promoting exercise and healthy eating should be welcomed, it is debatable how much will really change. Poverty and inequality in the UK need to be tackled. Otherwise, the obesity ‘crisis’, and many other social challenges, will only continue to get worse.

Get Involved!

– Write to your MP about the government’s failure to regulate the food and drink industry.

– Support The Canary so we can keep bringing you the stories that matter.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons

![This young boy in an ambulance has a silent and haunting plea to the world [VIDEO]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Screen-Shot-2016-08-18-at-15.09.51.png)

![Amid Western silence, Amnesty reveals the brutal secrets of Syria’s torture complex [VIDEO]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/230297_Syria-Detentions-Illustrations-of-Conditions-and-Torture-Practices.jpg)