Helen Sims is no ordinary writer – but then, her life has been far from ‘ordinary’. And, in her new book Taking Steps, she is determined to demonstrate that disabled people are so much more than their disability because, as a versatile writer and commentator, Sims certainly is.

Taking Steps is an extremely well-constructed collection of Sims’ poetry, short stories and commentary, which covers the emotional length and breadth of her childhood and adult years. In it, she treads a delicate line between appearing to write as a form of catharsis and wanting to make the reader stop, take notice and then question the subject matter in hand. But it’s a line that Sims never strays from – and it’s this personal investment she gives to her writing that makes her work so compelling.

There was, there is, no choice

Speaking to The Canary, Sims agrees that the process of putting pen to paper is cathartic, but explains there is much more to it:

I kept a ‘paper’ diary for years, and it certainly helped with my depression. Writing still does. It’s almost as if (when you put feelings down on paper – whether it be in a creative way or otherwise) I am clearing my mind. It doesn’t always work unfortunately, but it’s an outlet. There have been times when I’ve written things out, intending just to tear them up – but I kept them in the end, and they’ve been turned into pieces of work that I know have helped someone else.

It’s this idea of writing in the hope that the outcome will be to have “helped someone else” which shines through in Taking Steps. Because her brutal candidness means issues are tackled head-on, with no dressing-up. The reader is given the stark reality of situations many disabled people find themselves in from the beginning of the book.

Taking Steps opens with a foreword, giving us the author and campaigner’s backstory. Sims has lived with cerebral palsy all her life, and while this has undeniably shaped her as an individual, it’s not something she has allowed to define her. As she recounts at the start of the book, regarding being at a ‘mainstream’ school:

Eventually though, things settled down a bit and I found my niche. I was ‘skipping rope holder’ at play time. Part of me felt wonderful; so pleased and relieved that they wanted me to play with them. But it hurt too. I wanted to be the one skipping or playing hopscotch, and I hated being left out of ‘kiss chase’. However, I understood that it was just the way things had to be. There was, there is, no choice.

“There was, there is, no choice” is one of the most profound statements in the prologue and one which is crucial to understanding the rest of Sims’ work. It’s that resolution the author has come to – that acceptance – which drives her. She is, while not always content with life, unyielding in her self-awareness and determination to be more than her disability.

From Jane Eyre to Alan Ayckbourn

From an early age, Sims’ love for writing was apparent. As she recalls:

I started writing when I was about eight. I wrote little short stories first, and a little book about my disability for the school library. The poetry started a little later, aged about 12. I started writing because I love words, and I had ideas and feelings that I wanted to express. Also, I felt that it was something I could do.

While Taking Steps is a triplet of formats, it’s Sims’ poetry which stands out. The majority of it is either lyrical or ballad in style, and she employs the iambic pentameter frequently – deftly skipping from ‘ABBA’ to ‘ABCBC’, via ‘ABAB’, and even using a vers libre format on occasion, to great effect:

I prefer to write poetry (although I don’t do it as much as I used to) and for me it is more rewarding than prose. I love rhythm and the way that certain words sound when you put them together. I love, too, the challenge of creating images/imagery, especially if they can be used to convey a feeling or make a feeling easier to understand. Having said that, prose is great too. It really depends on what I want to get across. There are pros and cons to each form I think.

Orthodox poetry this is not, but it is of no consequence – as it’s the subject matter which is crucial in the book. Sims counts her influences, among others, as F Scott Fitzgerald and Charlotte Brontë (“Jane Eyre is my favourite novel”, she says) along with the James Herriot novels. “I spent time in the Yorkshire Dales on holiday as a child”, Sims recalls. “I think they capture a time that has gone. I really enjoy the quirkiness and the characters.”

There is something romantic and almost whimsical about a lot of her work. Simplicity discusses fondly the relationship with her husband, and When You Are Not With Me talks about yearning for someone who’s absent. But her standout works are the ones which are the most devastatingly honest.

Two of the most moving pieces are Dead and Baby, unfinished. In them, Sims openly talks about suffering a miscarriage, and the effect it had on herself and those around her. Heartbreakingly honest and brutal, she cares not for embellishment. She merely hits the reader with the stark and tragic reality of the event:

I really don’t know why I’m writing to you now,

I guess the private me needs to come out

Somehow.

I’m sorry baby that you could not stay,

And because I flushed you away.

“When you can’t have a child and so many of your friends are, it is so painful”, Sims says. “So many different emotions – and I wrote these poems to try and explain (to a good friend) what I was feeling. It worked, but I was crying as I wrote it.”

Sims says that Taking Steps was often very difficult and troubling to write, especially surrounding the subject matter above:

I particularly found the pieces about childlessness difficult, but I think it’s important to be honest about difficult issues in order to promote understanding of them. That goes for mental illness too. There is still a lot of stigma surrounding that, which we need to try and challenge/stop. People tend to fear what they don’t understand, don’t they? I hope that by writing about all these things (including disability), it will help increase understanding. I’m naturally a very open person though so maybe I didn’t find it as difficult as others might – and when I did struggle I thought of the goal again. Help people understand.

But Taking Steps is by no means mired in seriousness, which signifies the intelligence of her writing. She plays the reader, as such, by flipping between heavy, emotive work, and then laugh-out-loud pieces. There’s a touch of the Alan Ayckbourn about Sims, for example, in While You’re At The Shops:

While you’re down there,

Put the lottery on,

This time don’t get the numbers wrong!

Get some polish for Cindy’s shoes,

Find a cure for Andy’s flu.Granny rang,

Don’t forget her gin,

Or plastic bags for the kitchen bin.

Writers generally have work they’re most proud of, and for Sims, it’s the piece entitled Please:

It was written when I was fourteen and I had only been out of hospital for about seven weeks. (I had spent just under four months in hospital, a hundred miles from home having multiple orthopaedic surgeries (to help my Cerebral Palsy). I learnt to walk from scratch during that time, as an effort to improve my mobility.

When I came home I was terribly depressed and overwhelmed by everything. Readjusting to school, keeping up, pain, continued daily physio, loss of friendships. There were times when I was suicidal then, but I’m proud, because even at my worst, I managed to end that piece positively. Later that year, it won a local ‘World Aids Day’ poetry competition. It’s very special to me.

I get the impression that pride, and moreover praise, is not something Sims deals well with. She’s quick to praise others. For example, she dedicates the book to “all the NHS professionals that work so hard, despite often being underappreciated”. However, she was concerned that people may think Taking Steps was all about her, that in some way it was an exercise in massaging her ego. But you only have to talk to her about her campaigning for disability rights to realise it’s not personal gratification that drives her.

Making a difference – whatever it takes

Anger and frustration seep out when discussing the way disabled people are treated in the UK:

Disabled and ill people are in a far worse situation than we were before 2010. I’m watching the cause I love and believe in go backwards. The government has destroyed lives, and not just via cruel and unnecessary social security sanctions which have indirectly (and directly) been responsible for the deaths of thousands and thousands of disabled and ill people, but through loss of independence and self-esteem.

My own mental health has suffered as a result of us being labelled ‘scroungers’. Can they quantify people’s mental illness? Can they feel people’s excruciating pain? I doubt it, and yet the Department for Work and Pensions [DWP] decides how easy people’s futures are. They will judge me and countless others based on inflexible criteria, based on what they think they know, and will likely ignore doctors’ recommendations! I am a person, not a number on a page – and that goes for all of us who are facing and having to fight this – on top of everything else we have to cope with.

It’s this drive to try and improve the situation in the UK for disabled people, the long-term sick and those suffering with their mental health which, ultimately, Sims hopes Taking Steps will play a part in. When asked what she hoped to achieve with the book, she says:

I hope that it raises awareness of all the issues that are covered in it. I hope people see something of themselves. Give them something to identify with. That’s how you change attitudes – even if it’s a gradual process. But I want to entertain though, too.

Taking Steps meets all those criteria. It is a glorious collective, cradling the reader on a journey through the full spectrum of Sims’ emotional, well-worn path in life. It defies the prevailing customs of academia-led verse, and explodes as a gutsy miscellany of heartfelt, crucial reflections on a writer’s life and her interaction with the world. It is the work of someone who has ‘lived’.

As Sims says:

I started with an idea to turn everything negative that has happened to me into something bright, positive and strong (but real at the same time) that will help others – and hopefully I’ve done that.

If Taking Steps is to be judged on those benchmarks, then it is indeed bright, positive and strong – and acts as a potent force in dispelling so many myths surrounding the subjects she holds dear. A must-read by an author who now, after taking her own first steps into published writing, we will surely be seeing a lot more of in the months and years to come.

Get Involved

Support Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC).

Donate to PACE, the charity for children living with Cerebral Palsy.

Follow Helen Sims on Twitter.

Featured image via Graeme Parker

![It turns out the Daily Mail’s breastfeeding mother ‘squirted her boob’ story is one man’s brilliant hoax [IMAGES]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Screen-Shot-2016-08-06-at-5.31.09-PM.png)

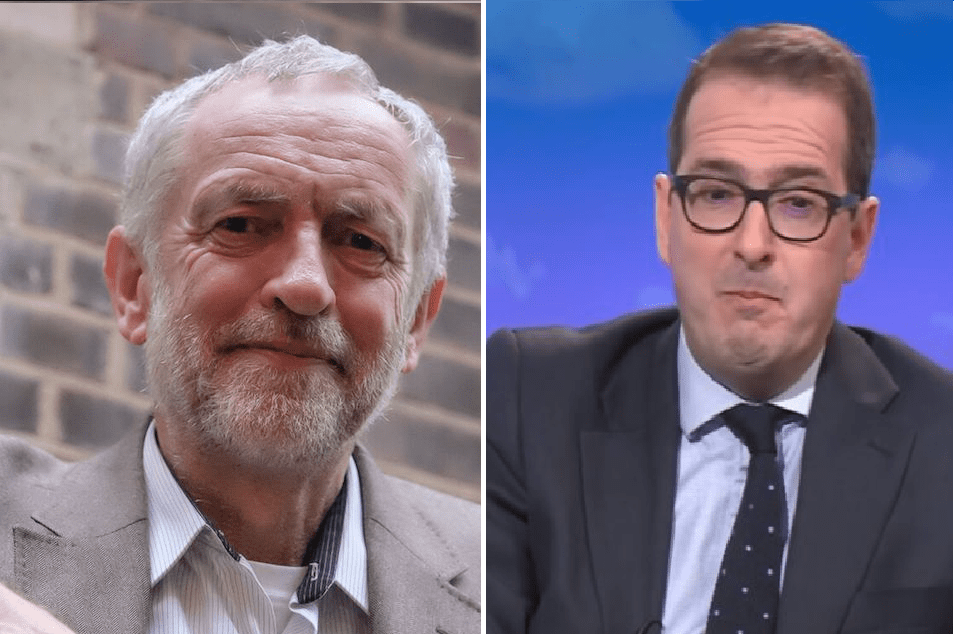

![REVEALED: The tweets Owen Smith doesn’t want you to see [IMAGES]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/000009-Tweets-Owen-Smith-doesnt-want-you-to-see-01.png)

![Owen Smith supporters are big fans of this new anti-Corbyn Twitter account, and it’s racist as hell [TWEETS]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Screen-Shot-2016-08-08-at-16.18.13.png)