One of the most devastating legacies of David Cameron’s leadership has just been revealed, and it’s a bitter pill for the nation to swallow.

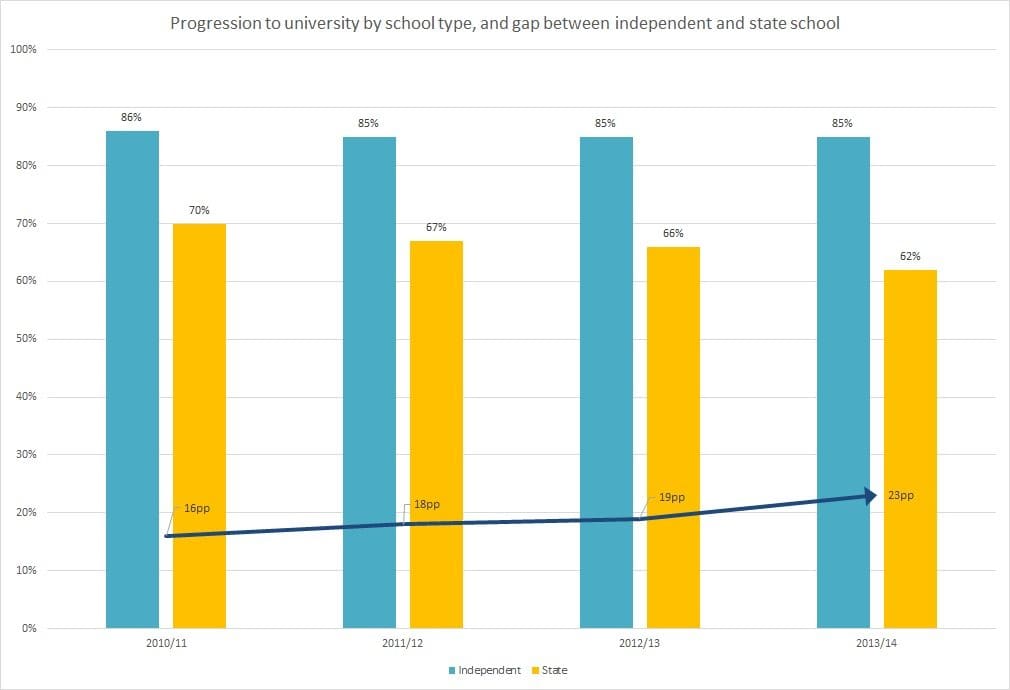

It has been revealed this week that the gap between the number of children from state schools and private schools making it to university widened significantly under David Cameron – as the impact of tuition fees took its toll on the aspirations of young people from less affluent backgrounds.

As Schools Week reported on 3 August:

Figures released by the Department for Education (DfE) this morning show that in 2013-14, just 62 per cent of state school pupils progressed to a higher education, compared with 85 per cent of independent school pupils.

As shown in the graph above, the gap has increased from 16 percentage points in 2010-11, to 23 percentage points in 2013-14.

Detailed figures show that this drop has come mainly from non-selective state schools (falling from 68 per cent to 60 per cent in the same period), although selective state schools saw a small drop in their proportion attending university in 2013-14, falling from 90 per cent throughout the previous three years to 88 per cent.

A spokesperson for the Sutton Trust, a social mobility charity, said: “It is seriously concerning that the proportion of state school students going on to higher education has decreased in the past five years. It is more than likely that this drop is linked to the tripling of tuition fees in 2012.”

The government’s report noted that the 2013-14 cohort was the first to be “fully affected” by the tuition fee changes.

What’s worse is that Theresa May’s government is putting yet further barriers in the way.

The maintenance grant which supported students from lower income families was scrapped on 1 August. Students whose annual family income is under £25,000 will now lose £3,387 a year of financial support. Instead, they will have to take out loans – further adding to the debt burden and further financialising the education system.

This speaks not only to the legacy of Cameron’s Conservatives, but also to that of New Labour – which introduced tuition fees in the first place, ushering in the financialisation of higher education.

The financialisation of higher education

It’s hard to believe that a little over a decade ago, we viewed higher education as a social service. We clubbed together to put our young people through university, as an investment in their (and our) future. But as manufacturing and many non-graduate jobs moved offshore to allow corporations to maximise profits from poor labour conditions abroad, a pending job crisis was foreseen.

This was the ‘changing economy and jobs landscape’ Tony Blair talked about in 1999 which led him to call for a target of 50% of young people attending university. His aim was to put more young people through university and create new graduate jobs for these young people to migrate to. The populace was told that in order to fund this expansion in student numbers, tuition fees were required to spread the burden.

The story was that, in order for more young people to go to university, fees were required. But a quick look at the facts proves this argument invalid on several grounds.

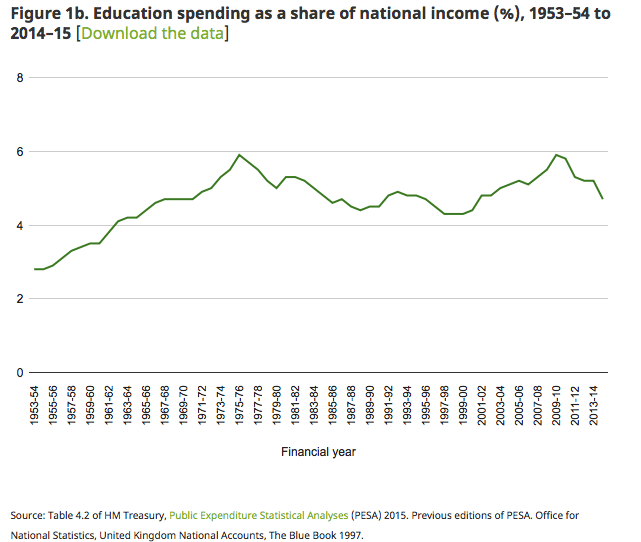

Firstly, the UK is not a leader of developed nations in terms of the percentage of its population receiving a university education. In fact, between 2000 and 2008 (after tuition fees were introduced), the UK fell from third to fifteenth in graduate numbers, according to OECD figures.

Secondly, several nations above the UK in this league table have not introduced tuition fees. In Finland, which tops the league, 80% of young women attend university and there are no tuition fees. Denmark, Sweden and Norway all outrank the UK, too, and none have introduced tuition fees.

So introducing tuition fees did not increase the UK student population any faster than the rest of the OECD. In fact, it has risen more slowly than elsewhere. And neither does a rising student population require the cost of education to be transferred to the student by way of tuition fees.

Nevertheless, the New Labour government introduced tuition fees, capped at £3,000 a year.

One of the first acts of the Coalition government was to introduce a new ceiling of £9,000 a year (despite the Liberal Democrat pledge to scrap tuition fees altogether), trebling the potential fees payable by students.

Making students pay more

Before 1998, student loans were payable over 60 monthly instalments, paid at the rate of inflation and the debt was cancelled when the graduate reached 50 years old. Between 1998 and 2012, student loans were based on income as a graduate. A graduate would pay 9% of their annual income each year once earning more than £15, 795 a year. At the moment, interest rates are capped on these loans, with graduates paying interest at either the RPI measure of inflation or banks’ base rate plus 1%, whichever is lower. Since 2012 it has risen to RPI plus 3%.

The government, after inducing young people into indebting themselves to fund a former public service, is now seeking to make a profit from the debt. In 2013, the government sold the pre-1998 student loan book to a debt management consortium for just £160m of the £900m owed.

A previously unseen report, commissioned on behalf of the government, reveals plans to sell off student loans taken out since 1998 and retrospectively raise the interest rates paid by graduates to increase the attractiveness of the loan book to private buyers. It also suggests creating a ‘synthetic hedge’ whereby the government pledges to underwrite all risk associated with the student debt. This means that, in the case of default, the tax payer covers the investor’s potential losses.

This would leave 3.6 million graduates facing sharp rises in their student loan repayments, while the tax payer stands as guarantor in the event students default on the debt, paying up to ensure private investors never lose a penny.

The legacy of David Cameron’s assault on higher education

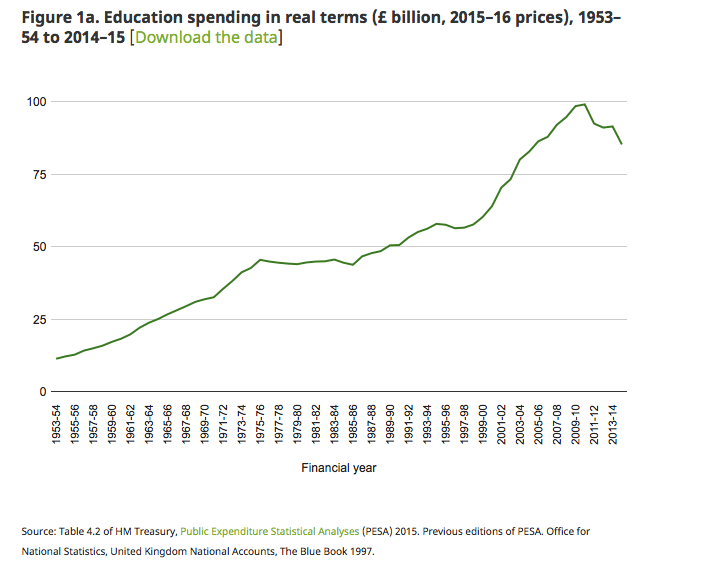

Since 2010, the Conservatives (and Liberal Democrats) have overseen a drop in public spending on education unprecedented in the last 40 years.

Back in 1999, upon the introduction of fees, higher education received £4.2bn each year of government funding. If spending had been maintained in line with inflation (which would translate into a cut in funding per student given the increased numbers), this figure would stand at £6.6bn today. But by 2012/13, funding had been cut by £1.2bn from the previous year, and was down to just £5.2bn. So more students, less funding.

In the longer term, it’s estimated that 39.4% of student loans will never be paid back, as graduates will not earn enough to afford the repayments before reaching the end of the repayment term. Selling the debt to private investors now, and making a future government responsible for the fall out, allows present-day governments to maintain their failing policies without the consequences becoming clear on their watch. But cracks are already beginning to show:

- Student numbers are lower now than in 2010.

- The UK has a lower percentage of 20-29 year olds enrolled in full or part time education than the OECD average – lower than Poland, Estonia, Hungary or Turkey (page 15).

- Since 2011, the UK government has actually cut student places by 25,000 and overseen a 40% drop in applications from mature and part time students.

So much for the Conservative Party’s claim of being the ‘party of aspiration’.

Warped logic

George Osborne made these decisions on the basis that there was a “basic unfairness in asking taxpayers to fund grants for people who are likely to earn a lot more than them”. But this is the sort of thinking that kills progress. We are a team. Local communities giving each other’s kids a leg up is the absolute foundation of social mobility. If we want it to be possible for a kid from an estate to be a doctor, a scientist or an engineer, we need to club together to make it happen. And if we want to benefit from the expertise of university-educated professionals, then we need to fund them too.

If we want to live in a country which makes things, invents things and cures things, we need to invest in each other. That’s the basic logic which drives nations forward and makes progress possible. It’s a spirit entirely lacking from the UK’s current neoliberal establishment in the Conservative Party, the Liberal Democrats, and the right-wing of the Labour Party. They know the price of everything, and the value of nothing.

Anyone who wants to see Britain set an example for the world, and see our children unlock the greatest possible sum of their potential, needs to vote for parties and leaders that think differently.

Featured Image via Flickr Creative Commons

![The Labour Party has issued another ban on pro-Corbyn members, and it’s ridiculous [IMAGE]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Corbyn-Labour-new-members.jpg)

![Benjamin Netanyahu accused of sabotaging peace, as Israeli authorities abuse Palestinian children [VIDEO]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/netanyahu1.jpg)