The BBC has let slip an underlying reason for its biased coverage, admitting that it fails to regulate its journalists for impartiality.

Numerous studies have already shown the BBC to be pro-Conservative and pro-business in its broadcasting. But now, a separate revelation here at The Canary could explain why.

It has become clear that the BBC can override a basic level of transparency in its operations through a loophole in Freedom of Information (FoI) requests put to the institution.

What’s more, the BBC has admitted that neither its unitary board (the BBC Trust) nor itself monitor or report upon staff conflicts of interest. Only upon initial employment do BBC journalists declare conflicts of interest.

The BBC editorial guidelines read:

A conflict of interest may arise when the external activities of anyone involved in making our content affects the BBC’s reputation for integrity, independence and high standards, or may be reasonably perceived to do so. Our audiences must be able to trust the BBC and be confident that our editorial decisions are not influenced by outside interests, political or commercial pressures, or any personal interests.

But if the BBC does not monitor its staff for conflicts of interest, then it simply cannot adhere to its own editorial guidelines or the moral standards they represent.

The story from the beginning

In December 2015, there was a Twitter dispute between BBC Newsnight policy maker Christopher Cook, RAF veteran, activist and author Harry Leslie Smith, and financial activist Joel Benjamin. It began with Cook sniping at the Twitter account Harry’s Last Stand, accusing the 93-year-old of employing junior staff as publishers and expressing disbelief that the veteran would tweet so frequently. Smith denied this, but Cook said he didn’t believe him and continued to badger him.

Benjamin saw this as a public service journalist using his position to discredit a prominent, outspoken Labour party supporter. This led him to investigate Cook.

It turns out that Cook had previously worked as a research assistant for Tory minister David Willetts, when Willetts was the Shadow Secretary of State for Education and Skills in 2005.

Cook then abandoned his political career in 2008 to become an education correspondent for the Financial Times (FT), but remained close to Willetts as they worked on a book together, entitled ‘The Pinch’.

While Cook worked for the FT, there was an ideological battle between Michael Gove and Willetts within the Conservative party. They clashed heavily on education policy, and Cook’s devotion to Willetts’ side of the battle is clear from his reporting at the FT. He used his journalistic position to repeatedly attack Gove, as Toby Young sneered in The Telegraph in 2011:

This is the latest in a string of “scoops” by Christopher Cook about Michael Gove and his advisers, nearly all of them intended to cause him maximum embarrassment.

After the FT, Cook joined the BBC Newsnight team. Curiously, only a couple of weeks after joining, his former boss Willetts was a guest on Newsnight. This struck Benjamin as odd. Cook had worked for Willetts, written a book with him, and used his position at the FT to attack his political opponents. He pondered – is this not something the BBC or the BBC Trust should look into as a potential conflict of interest?

The editorial guidelines would take issue not just if Cook had a conflict of interest but if he “may be reasonably perceived to do so” in the eyes of the public.

The BBC can legally undermine a basic level of transparency

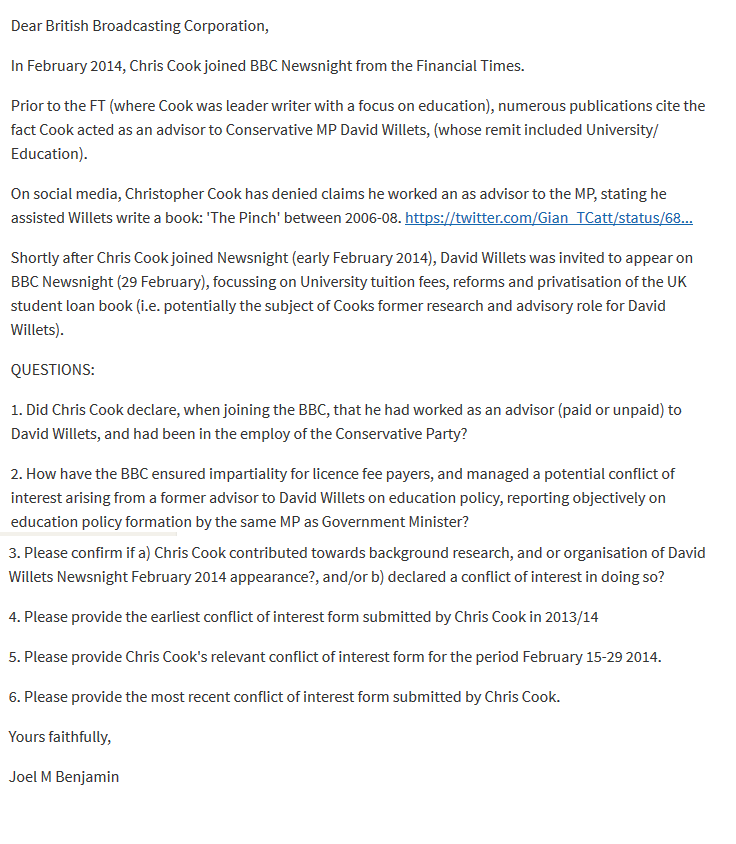

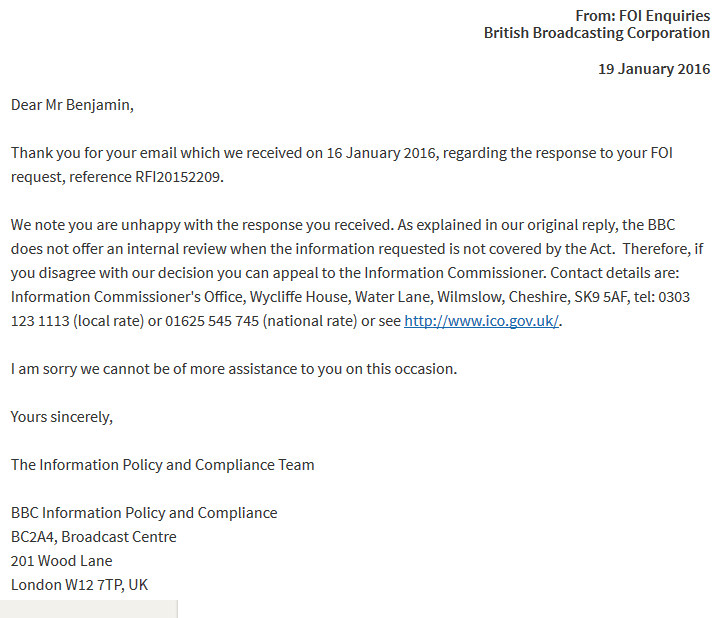

Upon discovering Cook’s strong link to Willetts, Benjamin submitted a FoI request to the BBC:

But the BBC rejected Benjamin’s request on the grounds of ‘journalistic output’:

Considering that the BBC consists of journalists doing journalism, this exemption seems very open to interpretation. The FoI request was not related to journalistic output, and was simply a legitimate request from a member of the public to check the standards of a public institution. In other words, this seems to be very much an issue about transparency.

According to the BBC’s own editorial guidelines, if Cook did have a conflict of interest, he should not have worked on that particular Newsnight show:

The Principles on conflicts of interest apply equally to everyone who makes our content. Independent producers should not have inappropriate outside interests which could undermine the integrity and impartiality of the programmes and content they produce for the BBC.

Relevant data from the Information Commissioners Office (ICO) confirms that there is legitimate public interest in transparency regarding the Registered Interests of Public Officials, or those whose roles are funded by public expenditure (like the BBC). The ICO states that such transparency “fosters trust in public authorities”. The ICO describes itself as:

The UK’s independent authority set up to uphold information rights in the public interest, promoting openness by public bodies and data privacy for individuals.

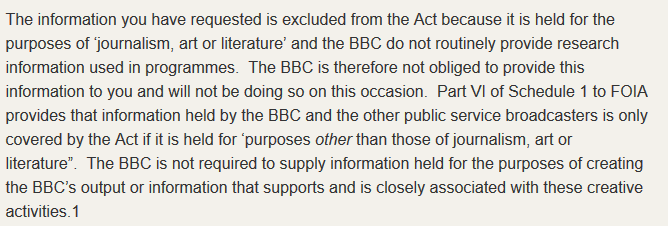

Benjamin cited the ICO data in a subsequent letter to the BBC, which contested their handling of his FoI request. He began:

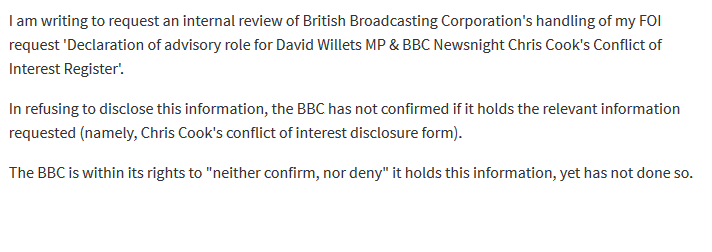

At the end, he said:

In other words, the public doesn’t need to know about Cook’s personal life, just what his jobs and moneyed interests are and have been in relation to the ethical standards of a public institution. Yet the BBC again refused:

In short, even with issues related to transparency, the BBC can still legally reject FoI requests that are within the public interest.

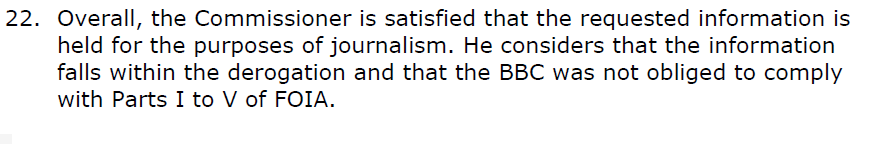

And in correspondence with Benjamin, the ICO backed the BBC’s decision:

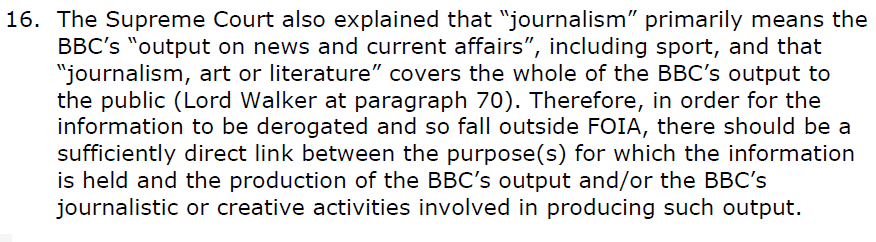

But it also confirmed the broad scope of the BBC’s ability to derogate FoI requests:

Crucially, the BBC routinely applies this exemption liberally and in response to a broad assortment of FoI requests. Back in 2012, an FoI response showed that between 2005 and 2011 the BBC had refused an average of 48% of FoI requests on these grounds of “journalism, art or literature”.

To put this into perspective, the percentage of FoI requests that were rejected, either in full or in part, within the UK in 2011 was 22.6%. Of the nation’s FoI requests that year, 44.8% were on the plainly legitimate grounds of requests including personal data.

Strikingly, the BBC rejects more than double the nationwide average (48%) on the same blanket grounds of “journalism, art or literature” – an exemption included within the Freedom of Information Act since 2005. Currently, if a member of the public submits an FoI request to this public institution, there is a near 50% chance it will be rejected on the same general terms.

A BBC spokesman confirmed the broad scope of the derogation:

These figures are simply a reflection of the law and the requests submitted. Where requests are covered by the Act the BBC is open and accountable and makes a huge range of information available. However, the BBC is not obliged to provide information excluded by the Act when it is held for the purposes of ‘journalism, art or literature’, allowing public service broadcasters to protect freedom of expression and maintain editorial independence. Given we’re the world’s leading public service broadcaster it’s little surprise that many questions fall within these topics.

But it is surprising that the exemption applies to “many questions” when there is legitimate public interest. And that’s the problem.

The BBC received an average of 1,351 FoI requests per year from 2005 to 2011. This being a strain on resources is one reason there should be appropriate grounds for the BBC to reject FoI requests. But the “journalism, art or literature” derogation is simply judicial overreach, and it must be updated and unpacked so it clearly lays out the specifics of when an FoI request should be refused in cooperation with the editorial guidelines. For example, if the request is not grounded in public interest and considered a waste of time and resources, it should be rejected.

At present, the exemption is open to arbitrary interpretation and therefore exploitation.

The BBC admits it doesn’t check its employees for impartiality

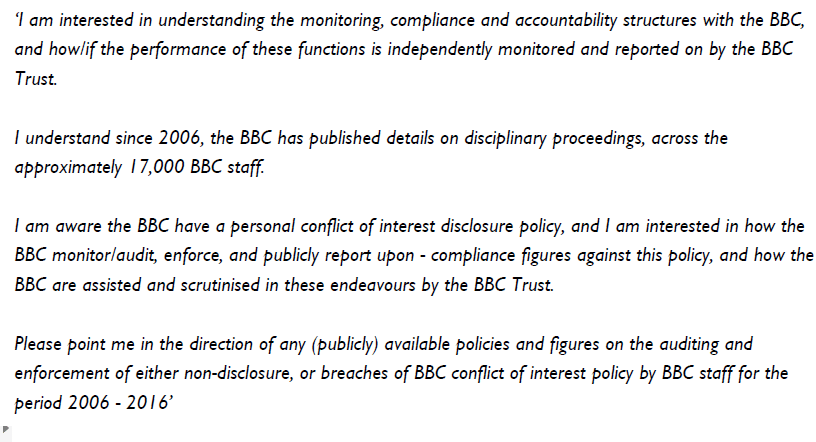

Subsequently, Benjamin submitted this request to the BBC and the BBC Trust:

The Trust Unit responded by stating that the BBC Trust does not regulate the biases of journalists:

This is despite the Trust’s description of itself:

The Trust is responsible for approving the BBC’s Editorial Guidelines. These Guidelines are the key foundation for the maintenance of high editorial standards in everything broadcast or produced by the BBC. They cover a range of standards including impartiality, harm and offence, accuracy, fairness, privacy and dealing with children and young people as contributors.

And the BBC responded by stating that its members of staff do declare conflicts of interest when they are initially employed, but that it doesn’t “monitor” said information:

In short, neither the BBC nor the BBC Trust regulate the activity of BBC journalists on a day-to-day basis when it comes to their potential biases.

The BBC neither confirmed nor denied its admission, saying:

The BBC is impartial and our journalists put their personal views to one side when they join the corporation. Our editorial guidelines on impartiality and conflicts of interest

can be found here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidelines/impartiality

But as well as being contrary to these editorial guidelines, the failure to properly regulate journalists may be at odds with EU law:

EU countries should ensure regular supervision of the use of public funding and the carrying out of the public service mandate.

There are large numbers of high profile individuals at the BBC with links to big business and the Conservative party. In this context, it is all the more significant that we assess these public service journalists for impartiality.

Fast forward to 2016, and Newsnight’s Cook is covering the government’s education policy for the BBC. Despite Cook’s strong ideological link to Conservative education policy, he has reported on Tory plans to force the transitioning of schools into academies.

The need for proper monitoring

A publicly funded broadcaster should be transparent by default. There should be an online database of conflict of interest disclosures from all journalists at the BBC.

But there isn’t, even at a point when Theresa May’s Investigatory Powers Bill would give the government access to citizens’ browsing history and metadata.

Both the government and the BBC are on our payroll, not vice versa. Yet they don’t even operate at a basic level of transparency.

At the BBC, there was a culture of covering up Jimmy Savile’s devastating activities. Savile gallivanting around as a star was seen as more important than the lives of the children he abused – who were treated as collateral damage by the BBC.

Without proper monitoring, staff at the BBC can exploit their trusted position to advance their own agendas on the back of the licence-fee payer.

As an example of alleged BBC corruption, the Trust is currently chaired by Rona Fairhead, who has been a HSBC director for many years. HSBC figures are not only “custodians” of the BBC’s pension fund, but are owners of, shareholders in, or financiers of 70% of the investment companies charged with managing the pension fund’s finances. And when you look at the 20 largest investments made by the fund, 13 of these have, again, direct financial links to HSBC.

Perhaps Cook should not have worked on a show with his former boss, especially considering his habit of bashing Willett’s political opponents at the FT. And perhaps he should not have been covering Conservative education policy. These are questions that deserve answers. But currently, the BBC isn’t even allowing them to be asked.

Get involved!

Sign the petition calling for an investigation into bias at the BBC.

Write to your MP if you believe the broadcaster must be more transparent.

Featured image via Matt Cornock.

![Theresa May’s silence on plight of British mother in Islamist detention is sickening [VIDEO]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Nazanin.jpg)