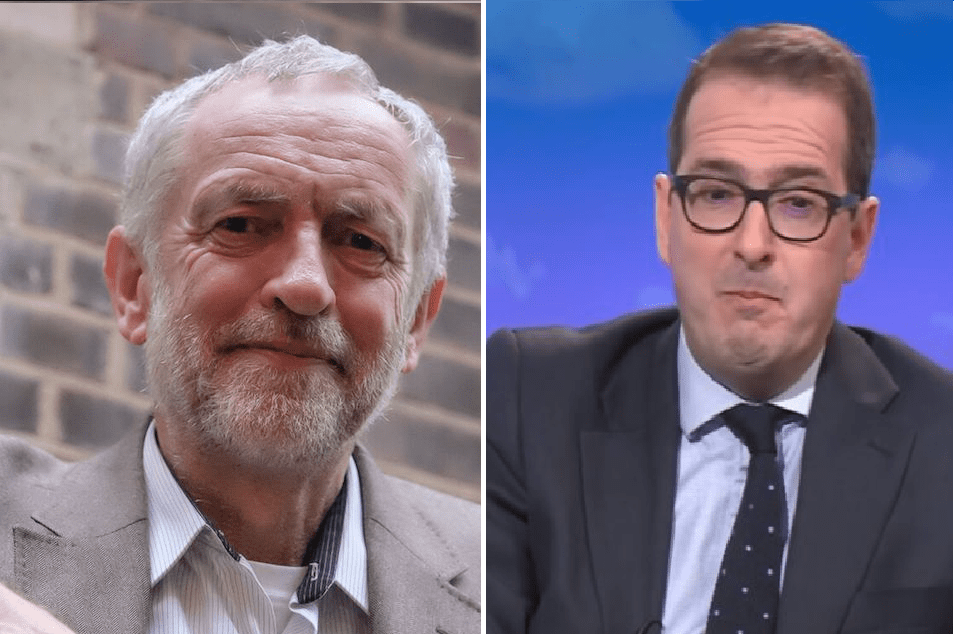

On 27 July, Owen Smith announced a host of policy pledges in order to win the vote of party members in the leadership election. While some appear to be directly lifted from Jeremy Corbyn’s own platform, his pledge to replace zero-hour contracts with “minimum hour” contracts doesn’t even come close to addressing the multitude of problems caused by exploitative working conditions.

No guaranteed hours

Zero-hour contracts have long been scrutinised. Earlier this year the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that over 800,000 people were now employed under a contract with no guaranteed minimum hours. Significantly, though, one in three of them stated that they would like more hours in their current job.

Following the investigation into the appalling conditions at Sports Direct, where 80% of warehouse staff are employed on a no minimum hours basis, it is clear that the insecurity of a zero-hours contract ensures workers won’t speak out about poor treatment and low pay for fear of losing hours they already don’t know if they’ll have.

Job insecurity

Smith is right to identify this as an injustice. He called zero-hour contracts:

Exploitative in their very essence and the hallmark of insecurity at work.

Which they certainly are. The majority of those employed on zero-hour contracts are women, the under 25s, over 65s, part-time workers and those in full-time education. In other words, some of the most vulnerable workers in the workforce.

Of course, students and part-time workers might benefit from the flexibility of a job with no set hours – but that soon wears off when they stop getting hours at all.

According to the TUC, the average weekly wage of a worker on a zero-hours contract is £188, compared with £479 for a permanent worker. What this means is that when people need more money to make rent or cover living costs, they must take hours offered no matter what – interfering with family life and their ability to plan ahead. It also means that, as they are registered employed, they may not receive government assistance.

The solution

With all this in mind, Smith’s response of a “minimum hours” contract seems practically laughable. He says:

You need to give people a contract to say, ‘here’s what you will be working’. It could be one, but I’m saying it shouldn’t be zero, we should invert that emphasis.

Smith is right that people should be able to know week-in, week-out that they will be working, and how much. But the assertion that replacing zero-hours with one-hour contracts will be better for staff and alleviate employment insecurity is totally out of touch with the workers themselves.

The Canary spoke to one former zero-hours employee who described how, as a part-time student, she had taken a zero-hours hospitality job under assurances that she would get 15 hours of work a week. In busy periods, she even worked more than that – some weeks working near-full-time hours, which caused difficulties with her degree. In others, she worked as few as three hours a week. And if she wanted to work less – that much-feted flexibility – she was told she couldn’t:

They could give me as little hours or as many as they wanted, but I wasn’t allowed to do the same. A zero contract is always for the employers’ benefit. Not for yours.

I overheard my manager telling my duty manager not to give me many hours any more, because I was older and more expensive to employ. When I looked into this as possible age discrimination, it seems I had no right to complain about it because of my zero-hour contract. I had no real rights.

Employers still win

Businesses like zero-hour contracts because they can utilise the labour of casual staff without having any commitments to them, paying them based on the work that they need them to do. Not being obliged to offer any hours is great for those where service needs ebb and flow and employees traditionally have less power, which is why these contracts are so popular in the hotel, food service, health and social work industries.

However, if all an employer has to do to circumvent this is to offer a minimum of one hour a week, or even five hours a week, there is nothing to stop them continuing to offer assurances to workers that they will receive more hours. And they can still give longer hours during the periods they need them, while offering the bare minimum when they don’t.

It seems clear, though not to Smith, that tackling this rampant exploitation is going to require addressing the employers themselves – and not just the contracts they give out.

Get involved!

Contact your MP and urge them to oppose the rise in zero-hour contracts.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons.

![Hillary Clinton tests out her powers of hypnosis at Philadelphia Democrat convention [VIDEO]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Hillary3-min-e1469717798225.png)