Just weeks away from the Olympics, Brazil has been plunged into political chaos. The government has changed hands in a controversial coup, and protests have filled the streets. But what’s behind these developments? And what impact might they have on Rio 2016?

In recent years, the USA has already supported coups against democratically-elected governments in Honduras and Paraguay. And this process, says the leader of Brazil’s ruling centre-left party, is now:

spreading through [a] Latin America in which coups, once carried out by the military, now occur with a legal facade

The Canary has written recently about the influence that global political and media elites have had on the current instability in Venezuela. But Brazil has also been a target. As Nobel Peace Prize winner Pérez Esquivel has said:

What is happening in Brazil is part of a US project for recolonising the continent.

Why would elites want to take down the Brazilian government?

From 1964 to 1985, a US-backed right-wing military dictatorship ruled over Brazil, much like in most other Latin American countries during this period. The main legal opposition was a centrist coalition which is now called the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (or PMDB).

After the fall of the Soviet Union, US interference in Latin America became much less obvious, and an environment of increasing democracy saw the left-of-centre Workers’ Party (PT) elected into power in late 2002 – on a platform of gradual social reforms.

Capitalism still thrived, but the PT government launched plans which have so far lifted around 50 million people out of poverty. In 2013, the Guardian wrote about how Brazil had become “a worldwide reference… of how to fight poverty”.

In 2014, the UN’s World Food Programme called the country “a champion in the fight against hunger”, speaking about how its achievements deserved the world’s attention. The PT also increased health and education spending significantly.

The PT is far from perfect

Attempting to reconcile capitalism and socialism, the PT stepped carefully, and failed to reform what Red Pepper has called “a deficient, unrepresentative system” of government. This means that the military-era system, which leaves corporate lobbies with immense power, is still alive and well today. At the same time, Brazil’s wealthiest citizens still control most of Brazil’s land, businesses, and media outlets, while state authorities continue to commit abuses (over 3,000 people were killed by police officers in 2015 alone).

But after decades of brutal repression, the Brazilian left was finally making significant steps forward, so little noise was made about the PT’s failures.

When Dilma Rousseff took the reins of the PT in 2011, however, progress seemed to stall. The new president, who had been tortured during the military dictatorship for her guerrilla activity, suffered the most after Brazil’s economy stalled in 2013. She was re-elected in 2015 thanks to an alliance with the PMDB – a party once described by a US diplomat as an “opportunistic” party with “no ideology or policy framework”.

After this re-election, Red Pepper says, Rousseff:

swung further to the right, with a series of neoliberal reforms and the promulgation of a dangerous – and entirely unnecessary – anti-terrorism law

But her government:

never descended to the depths of corruption, self-interest and exchange of favours of the other parties

University of São Paulo lecturer Christian Dunker says:

Remaining in power became more important than transforming power, and the need for alliances and concessions took the PT in the worst possible direction.

Massive global events like the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, meanwhile, were seen to have dubious legacies and to favour elites more than ordinary citizens.

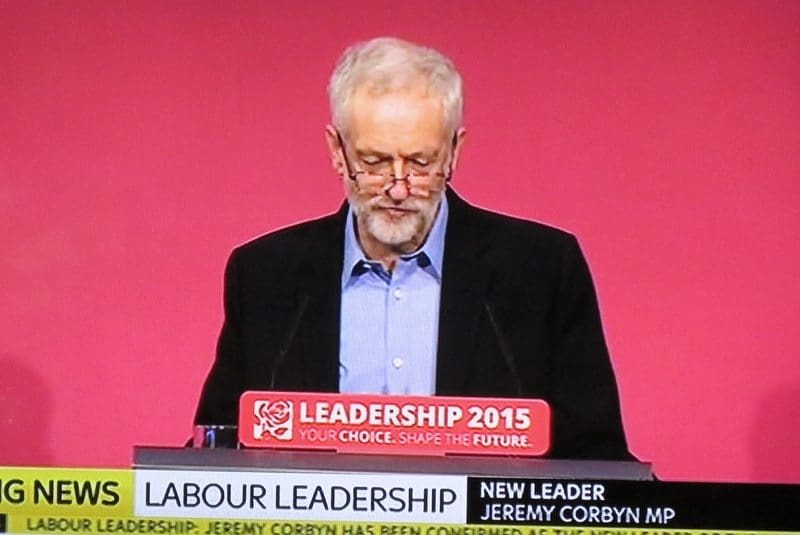

The PT now has much less support than it did in 2002 and, according to University of São Paulo lecturer Ricardo Musse, this situation will only change via an “internal struggle” (like that which saw Jeremy Corbyn elected leader of Britain’s Labour party) or through the “creation of new politics groups” (like Podemos in Spain).

The impeachment coup

After months of media-incited protests, Rousseff was removed from office on 12 May 2016 for up to 180 days, pending impeachment hearings related to her government allegedly concealing an increasing budget deficit. She called her suspension “a coup attempt“.

Brazil’s wealthy Vice President, the PMDB’s Michel Temer, immediately became Interim President.

The Intercept’s Glenn Greenwald soon said:

a core objective of the impeachment… was to empower the actual thieves in Brasilia and enable them to impede, obstruct, and ultimately kill the ongoing Car Wash investigation [an investigation focused on money laundering and bribery related to state oil contracts]

Indeed, leaked recordings shortly after the coup showed that one of Temer’s closest allies had actually conspired to remove Rousseff in order to stop the investigations (of which he was a target). At the same time, a third of Temer’s chosen cabinet was implicated in the probe.

Temer himself, who WikiLeaks has accused of serving as a US embassy informant, has also been the target of a number of corruption investigations, and he has recently been convicted for spending his own money on a previous election campaign, exceeding legal limits in the process. He’s now banned from running for political office for eight years.

Yes, you read that right. Temer can somehow continue as Interim President in spite of being banned from running for office for eight years.

Anti-corruption group Transparency International promptly announced it would not speak to Temer’s regime until it purged the corrupt from its own ranks. Meanwhile, Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), Luis Almagro, insisted the accusations made against Rousseff were “not crimes“, and that she was being treated unfairly because previous presidents had also performed such actions. And considering that many of the politicians pushing for impeachment face corruption accusations themselves, Almagro said:

I am worried about the credibility of some of those who are going to judge or decide this impeachment process

The policies of the coup regime and popular resistance

Temer quickly created a new cabinet full of white men with large corporate interests. Within days, they reversed a number of Rousseff’s progressive policies, promised to slash public spending, and made it clear that privatising state industries was a priority. They also scrapped the Ministries of Women, Racial Equality, and Human Rights (among others).

Jacobin calls the coup “a stunning transfer of power to the country’s elites“, while Truth Out insists that the interim regime is acting to “balance the budget on the backs of the poor“. Glenn Greenwald has gone even further, saying:

This isn’t merely the destruction of democracy in the world’s fifth most populous country, nor the imposition of an agenda of privatization and attacks on the poor for the benefit of international plutocrats. It’s literally the empowerment of dirty, corrupt operators…

No wonder Temer currently has an approval rating as low as 2%.

Brazilian citizens haven’t been silent, though. So far, they have responded by:

- Bringing tens of thousands together in protests against the staffing of Temer’s regime with representatives from unelected parties. In the words of one protester: “We don’t necessarily support Dilma’s government, but we do support democracy”.

- By occupying Temer’s regional offices in Sao Paulo.

- By hitting the streets to call for Temer’s removal from power, resisting police violence in the process.

In response to these protests, Temer recently ordered authorities to spy on the PT, suspecting it was orchestrating the resistance.

Before and after: the role of the USA

In Venezuela, where a government independent of the United States is still in charge, the superpower has been very vocal in its support of the opposition’s challenges. In Brazil, on the other hand, the interim government is completely in line with US interests – so Washington has remained silent about the dubious constitutional nature of the coup.

On 6 June, The Intercept’s Zaid Jilani spoke about the comments of US State Department Spokesperson Mark Toner regarding Brazil and Venezuela, and how he had effectively ignored the situation in Brazil while giving long and critical responses on developments in Venezuela. Toner claimed to be “very concerned” about Venezuela, but said “I don’t have anything to comment” when asked about Brazil.

Maybe Toner was silent because the leader of impeachment proceedings in Brazil’s senate visited Washington for three days just after Rousseff’s suspension. Or maybe because previous and current US ambassadors to Brazil have allegedly participated in the overthrowing of other Latin American governments in the past.

While the USA tries to maintain a façade of neutrality regarding Brazil, however, Centre for Economic and Policy Research Co-director Mark Weisbrot insists that:

everybody who is doing the actual coup knows… the US is on their side

The reality of Brazil’s coup

The PT has clearly made errors, but there has also been a very clear campaign led by Brazil’s elites to overthrow their country’s democratically-elected government and overturn measures that benefit its most vulnerable and exploited citizens. The PT’s errors aside, the empowerment of citizens already at the top of society is nothing to celebrate.

Whatever the world’s corporate media may tell us, there has been a coup in Brazil. And as the Olympics get closer and closer, we should all stand alongside the Brazilian people in their fight for democracy.

Get involved!

– Read The Canary‘s previous articles on Latin America.

– Question everything you hear in the corporate media.

– Support The Canary as we seek to amplify the voices of the voiceless.

Featured image via National Olympic Committee and Agência Brasil