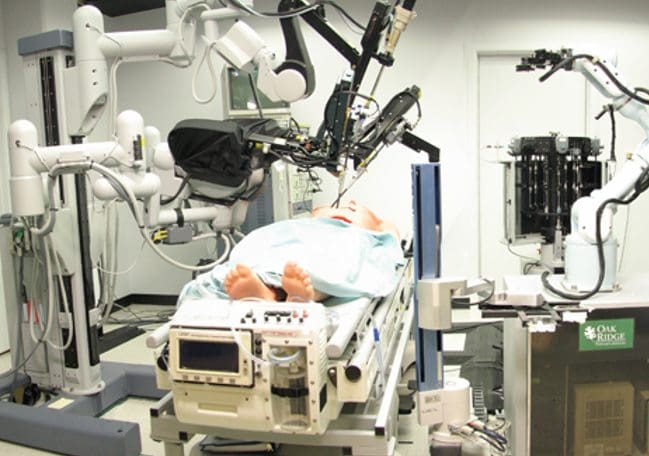

A report into how to make the NHS workforce more productive has caused controversy, after its recommendations included having non-registered staff doing the jobs of qualified doctors and nurses.

The study by the Nuffield Trust entitled “Reshaping the Workforce” has been approved by NHS England and will see nurses, paramedics and pharmacists trained to cover for doctors, along with non-registered staff being given responsibilities usually reserved for clinical professionals.

In fairness to the Nuffield Trust report, it is entirely balanced and well written. It utilises what is known in other industries as a SWOT analysis; that is, it identifies strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats surrounding the plans. SWOT analyses are most commonly found in the hotel industry and are fundamentally used as a cost saving/profit increasing exercise.

But when these efficiency promoting and cost saving measures are applied to the NHS – should we be worried?

The devil is in the detail:

In the report, its authors state:

The NHS needs to evolve from an illness-based, provider-led system towards one that is patient-led, preventative in focus and offers care closer to home. There is an urgent need to reshape the NHS workforce to equip it to meet the changing demand from the population it serves, [and] there are opportunities to develop the current workforce at all grades: from redeploying support staff, extending the skills of registered professionals and training advanced practitioners. Extending the roles of the non-medical professional workforce provides opportunities to manage the growing burden of chronic disease more efficiently and effectively. We anticipate that, in the future, care will be supplied predominantly by non medical staff, with patients playing a much more active role in their own care.

The report cites numerous case studies to support its recommendations. One such example is that of assistant practitioners (non-registered staff) working in community mental health teams. Originally commissioned in 2009 and rolled out in 2012, the idea was that these staff would conduct basic health checks on patients with mental illnesses – including blood testing and carrying out electrocardiograms (ECGs).

The assistants are managed by an advanced practice nurse, who is not part of the community mental health team. The assistant practitioners are monitored weekly by the nurses in the clinic and have a monthly meeting outside the clinic to discuss any issues. The study concludes that:

The support [assistant practitioner] workforce is highly flexible. The short training times mean that numbers can be expanded relatively rapidly. There is good evidence that support workers can provide good-quality, patient-focused care. They can reduce the workload of more highly qualified staff. But support workers should not be seen as a substitute for registered nursing staff in an acute hospital setting.

Overall, the report also looked into: ‘extended roles’ for registered professionals taking on tasks not traditionally within their scope of practice but which do not require training to Masters degree level; applying the same for advanced practitioners who are suitably qualified and increasing the scope of physician associates (dependent health care professionals who have been trained in the medical model and work with the supervision of a doctor or surgeon).

The report concludes that there are opportunities for:

more patient-focused care; improved quality of care and outcomes; improved team working and support; better use of resources; helping address workforce gaps and new and more rewarding career pathways.

It also identifies the risks involved with this strategy that may:

increase demand and service costs; supplement rather than substitute for other staff; cost rather than save; threaten the quality of care and fragment it.

As with the widespread use of SWOT analyses in hotels, another comparison with that industry can be drawn.

“Cross-training” is one of the most utilised methods of reducing wage bills in the hotel industry. You essentially get all your staff from different departments (housekeeping, food and beverage, kitchen etc) to have a rudimentary knowledge of working in every other department.

When a department is short staffed, you can pull another team member from elsewhere in the hotel to jump in and temporarily cover. It saves a hotel the cost of employing the correct quota of staff for each department, and ensures that as a business it is achieving maximum productivity. However the skill set of employees is often watered-down, and it is a risky strategy in terms of ensuring that basic staffing levels are maintained at all time. It is essentially a cost saving exercise.

Cut through all the nimble-fingered semantics contained in the Nuffield report – and a cost saving exercise is essentially what we have. One which has some serious flaws.

Show me the money:

The report fails to put any meat on the bones whatsoever regarding whether the case studies it cites actually saved any money. It did state:

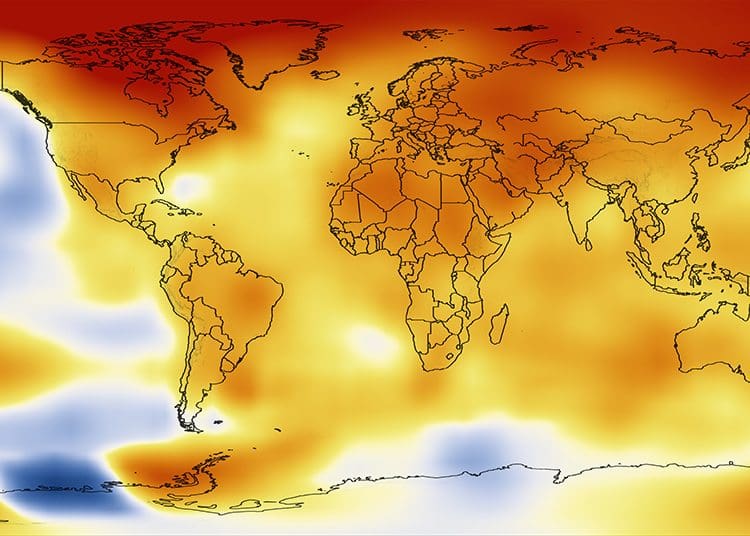

The NHS faces a £22 billion gap in its finances by 2020. Demand for NHS services, from a growing and ageing population, is projected to rise by 6.6 per cent by 2020. In social care, a gap between demand and available funding of between £2.8 billion and £3.5 billion will emerge by 2019/20. In many areas, the remaining front-line staff are left to absorb the rising demand for care into their day-to-day workload, a challenge that is magnified as the demand for workforce time is estimated to be growing at twice the rate of the overall growth in population.

All well, good, and somewhat worrying. But the recommendations that the report makes do not specify whether they will induce a positive net reduction in NHS costs, or simply add to already strained budgets.

In the case study of the assistant practitioners working with mental health patients, the report fails to acknowledge whether there were any direct cost savings via a reduction in pay. Nor does it assess whether any indirect efficiencies were quantifiable from the additional health checks that were being undertaken. It does, however, identify that:

increasing the number of health care support workers [assistant practitioners] did not reduce mortality rates. [A study in 2016 found] that the support workforce could not substitute for registered nurses in ensuring patient safety.

This leads on to another, more obvious flaw in the premise. With the best will in the world, surely unregistered staff are no replacement for those who have undergone years of training and ‘on-the-job’ learning?

Cost saving by skill reduction:

In a separate report by Skills for Health on assistant practitioners, concerns are levelled that:

courses are neither sufficiently general for all the students being sent on them nor sufficiently specialist for the specific occupational areas in which assistant practitioners work. Some specialist foundation degrees have been closed and replaced by programmes with common cores and specialist modules; however, fluctuations in trainee numbers, changes in commissioning policies and reductions in funding have led to fears about future sustainability.

In layman’s terms: an assistant practitioner will take a two-year foundation degree. A registered general nurse will usually take a 4-year bachelor’s degree. It doesn’t take a PhD to notice a fundamental flaw there.

Furthermore, the case study mentions that staff who were unqualified in mental health were working in that field, albeit in an auxiliary role. This, however, sets a somewhat concerning precedent. With the budget for mental health already having been reduced by 8% since 2010, leaving patients accessing those services already seeing cutbacks, is it the right time to be further reducing their access to professionals?

A case in point would be the tragic death of John Taylor Partridge, who committed suicide after discharging himself from hospital at the weekend when the community mental health team were unavailable. Now that mental health services are already stretched, every opportunity should be made to have patients engage with qualified practitioners, whatever the scenario.

Ignoring MPs advice:

The Nuffield report also flies in the face of a meeting of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) last week, investigating the clinical supply of staffing in the NHS. It’s conclusions were damning, and cast serious doubt over whether any of the Nuffield recommendations could be realistically implemented.

The PAC broadly stated that unrealistic efficiency targets have led to staffing shortfalls; that efforts to retain clinical staff are not well managed; that the shortage of nurses will continue for the next three years; that innaccurate headcount planning has led to an increase in agency staff; that health bodies are not making well-informed decision about workforce planning and that no attempt has been made to assess staffing requirements for a seven-day NHS.

The government’s proposed seven-day NHS is crucial in this. Chair of the PAC Meg Hillier slammed the Department of Health and NHS England plans, saying:

Taxpayers are being asked to accept uncosted plans for a seven-day NHS – plans which therefore present a further serious risk to public money. It beggars belief that such a major policy should be advanced with so flimsy a notion of how it will be funded – namely, from money earmarked to cover all additional spending in the NHS to the end of the decade. Taxpayers are entitled to ask questions about the financial security of the NHS and the level of service it is able to provide both now and in the future.

So when we already have an NHS that is chronically understaffed, that doesn’t plan its staff duties appropriately and is over-reliant on agency workers how can stretching the workforce even more – both via a seven-day NHS and the Nuffield plans – going to help?

The case studies cited in the Nuffield report go back as far as 2006, when the NHS was in a completely different position. Between 2000-2010 there was a 7% real-terms increase in NHS spending – the highest in history. Currently we are looking at a real-terms increase of just 0.9% by between 2010-2021. Comparing like-for-like regarding your workforce planning when the financial constraints are so vastly disparate is doomed to failure from the outset. Any efficiency measures implemented in the future need to be commensurate with the budgets they are constrained by. Not whimsically rooted in a past era.

The issues regarding the finances also extend to how the training required to diversify the workforce will be delivered.

Squeezing the budget dry:

The Nuffield report states that Health Education England (HEE) would be responsible for the delivery of some of the training, but also:

the proportion of HEE’s budget that is given to this activity is very small. In 2015/16 it amounted to just 4 per cent of HEE’s total budget – £205 million – with a prospect of a significant reduction in 2016/17 given the planned cut in HEE’s budget for its general workforce development activities as a result of the spending review. The proposed cuts to the HEE budget put this funding at risk. These cuts are short-sighted and counterproductive. They will undermine the capacity of the NHS to develop the new models of care.

The report recommends that the HEE budget is ring-fenced to ensure that the required training to implement its plans can be delivered. Without irony.

Unless the Nuffield Trust has some magic money beans, ring-fencing of the HEE budget will either be impossible, or be at the detriment of another area of the NHS. We have already seen this with the government’s proposals for an increase in spending on mental health services. The government proffered a £1.25bn increase in the budget between 2015-2020. However, this is not new money, but part of the £8bn that was pledged in 2015 for the Conservatives seven-day NHS plans. The axe, therefore, to have to pay for an increase in mental health spending will have to fall somewhere else.

Reacting to the proposals, Katherine Murphy the chief executive of the Patients Association, said:

The proposed new roles and extra responsibilities for existing staff should not be adopted as a ‘quick fix’ solution to the complex staffing problems within the NHS, nor be seen as a cheaper alternative to highly qualified staff. These proposals will not solve the shortage of skilled doctors and nurses across the health service and should not aim to do so. Instead, the government needs to do more to invest in the training and retaining of these qualified practitioners.

What the Nuffield Trust appears to be trying to do is fit a square peg in a round hole. While its proposals, say, ten-years ago may have been a sensible, long term plan to diversify the NHS workforce and in some way prevent frontline shocks to the system – this is no longer the case.

We have an NHS already crippled by underfunding, staffing shortages and top-down administrative blundering by a government whose main agenda is arguably one of privatisation-by-stealth. The Nuffield Trust proposals may seem somewhat innocuous, but when viewed through the prism of reducing costs to make a business look more attractive to the private sector – the image changes.

What the NHS needs is serious investment in both its infrastructure and its workforce to ensure that it is sustainable in the long-term. What the Nuffield proposals would do is merely put a sticking plaster on a broken leg.

There’s been enough quick fixes in the NHS to last it a lifetime. It now needs serious, remedial action.

Get involved.

Support the Justice for Health campaign.

Support the 650 local campaigns to Save Our NHS.

Image via Derek Winnert