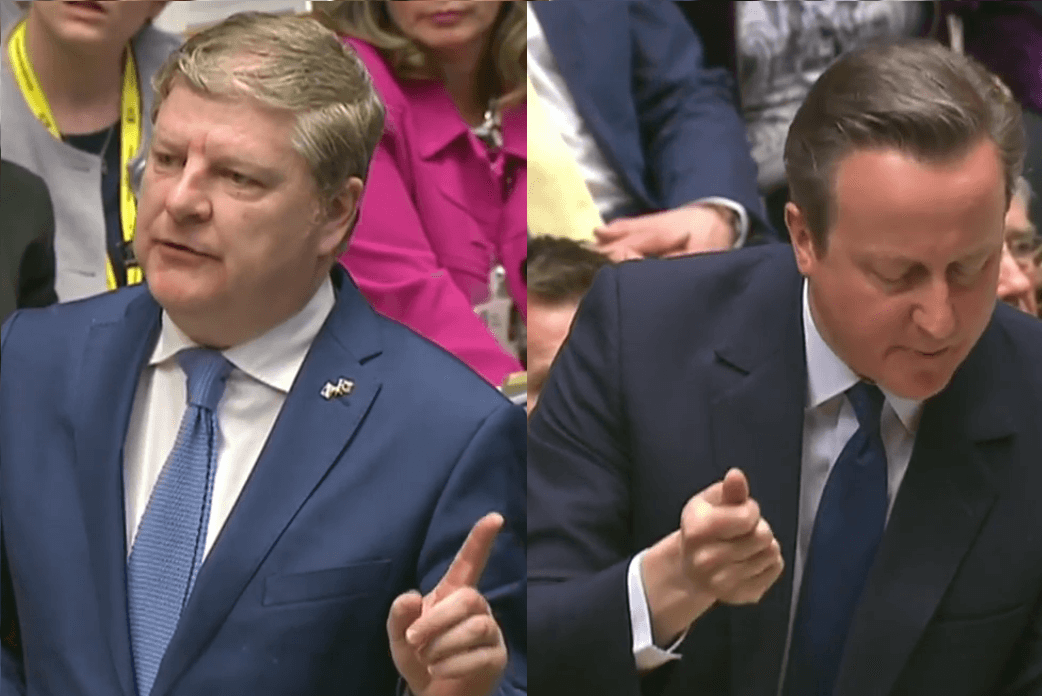

At Prime Minister’s Questions on Wednesday, Jeremy Corbyn asked David Cameron just who supports the government’s plan to force all schools in England to become academies. In his reply, the Prime Minister inadvertently admitted that the answer is: nobody at all, except the academy chains that stand to profit from it.

At PMQs this week, Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn asked the Prime Minister:

Who actually does want this top-down reorganisation he’s imposing on our education system?

David Cameron could only muster three answers: the Chief Inspector of Schools Michael Wilshaw; the OECD; and academy trusts themselves.

David Cameron is forced to answer who wants academisation for the education sector #PMQs https://t.co/9h77tg9KUt https://t.co/rCcCu1Cmow

— Sky News (@SkyNews) April 27, 2016

His failure to mention teachers, parents or headteachers – who have all been speaking out against academisation in force – echoed around the chamber. Less obvious was the fact that two of his answers aren’t exactly wholehearted supporters of his plans, and the third stands to profit from them financially.

1. The Chief Inspector of Schools

Leading the clamour of support for the government’s forced academisation of schools, according to Cameron, is Ofsted’s Chief Inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw. This is what Cameron said about him:

Let’s start with Michael Wilshaw, the Chief Inspector of Schools – I think someone quite worthwhile listening to: ‘Academisation can lead to rapid improvements and I firmly believe it’s right to give more autonomy to the front line.’

Wilshaw did say this. He said it in a letter (pdf) he wrote to Education Secretary Nicky Morgan in March of this year. But the quote Cameron lifted was a rare example of positivity in a long and scathing warning that several academy chains are performing worse than local authority schools.

Here are some other quotes from Wilshaw’s letter:

Despite having operated for a number of years, many of the [multi-academy] trusts [MATs] manifested the same weaknesses as the worst performing local authorities and offered the same excuses. Indeed, one chief executive blamed parents for pupils’ poor attendance affecting pupils’ performance. There has been much criticism in the past of local authorities failing to take swift action with struggling schools. Given the impetus of the academies programme to bring about rapid improvement, it is of great concern that we are not seeing this in these seven MATs and that, in some cases, we have even seen decline.

Across seven multi-academy trusts running 220 schools, Wilshaw wrote, inspectors found many of the following concerns:

Poor progress and attainment, particularly at Key Stage 4; leaders not doing enough to improve attendance or behaviour; inflated views of the quality of teaching and insufficient scrutiny of the impact of teaching on pupils’ progress; a lack of strategic oversight by the trust of all academies; a lack of urgency to tackle weak leadership at senior and middle levels; insufficient challenge from governors and trustees who accepted information from senior leaders without robust interrogation of its accuracy; confusion over governance structures, reflected in the lack of clarity around the roles and responsibilities of the central trust and the local governing boards of constituent academies.

Wilshaw was particularly concerned that many academies were failing their most disadvantaged pupils.

Given these worrying findings about the performance of disadvantaged pupils and the lack of leadership capacity and strategic oversight by trustees, salary levels for the chief executives of some of these MATs do not appear to be commensurate with the level of performance of their trusts or constituent academies. The average pay of the chief executives in these seven trusts is higher than the Prime Minister’s salary, with one chief executive’s salary reaching £225k. This poor use of public money is compounded by some trusts holding very large cash reserves that are not being spent on raising standards. For example, at the end of August 2015, these seven trusts had total cash in the bank of £111 million. Furthermore, some of these trusts are spending money on expensive consultants or advisers to compensate for deficits in leadership. Put together, these seven trusts spent at least £8.5 million on education consultancy in 2014/15 alone.

The government went on to ignore the findings in Wilshaws advice note, with a Department for Education spokesperson dismissing it as “a partial and skewed picture”. Nothing like Cameron’s selective quoting, then.

2. The OECD

Next, Cameron called the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as a witness for the defence, quoting the organisation as saying it viewed the trend towards academies as:

a very promising development in the UK, which used to have a rather prescriptive education system.

This is a quote from Andreas Schleicher, the OECD’s education expert, from evidence he gave to MPs in 2014, long before the idea of forcing schools to become academies had been seriously proposed.

Schleiger went on to warn MPs that autonomy alone was not the way to improve schools:

We cannot say that increasing school autonomy will necessarily yield an increase in outcomes because autonomy always operates in a context… there are many aspects that are at least as important [as autonomy]: the level of standards, the level of people you get into the teaching system and the investment countries make in their teachers.

In fact, Schleiger has warned that more autonomy can sometimes, as in the case of the United States, be “part of the problem”:

You need a very strong education system to make autonomy work, you can’t leave it to market forces alone.

Finally, the BBC reports that Schleiger believes moving decision-making away from schools and to academy chains “would reduce the advantage of such local flexibility and risked reducing a school’s sense of ‘ownership’.”

Again, not exactly the ringing endorsement from the OECD that Cameron presented to parliament.

3. Academy trusts

Cameron’s third and final answer to Corbyn’s question was somewhat desperate:

What about endless academy trusts who support it?

This hardly needs unpicking. The academy chains benefit financially from academisation. As The Canary has previously reported:

When schools become academies the property deeds are handed over at no cost to unaccountable academy chains. Often, the ownership of the public land, institutions and school equipment is entirely transferred to the private sector.

The academies also get more power over their own budgets – and many of them are using that power to spend taxpayers’ money on outsourcing school services to private companies owned by the academy chains’ directors or trustees or their relatives. According to the National Audit Office, nearly half of academy trusts have engaged in such ‘related party transactions’ – handing themselves £71m of taxpayer money in 2013 alone.

So we’ll give Cameron the third one: academy chains do support academisation. That’s how their bosses – which include many Conservative party insiders – make their money.

Almost no support for government plans, but Cameron is pushing forward

It’s hardly surprising that Cameron struggled to come up with anyone independent who truly supports his academisation plans. Almost nobody does. Even Conservative backbenchers are rebelling, triggering recent speculation that the government was planning a partial U-turn on academies. But Cameron insisted on Wednesday that “we’re going to have academies for all and it’s going to be in the Queen’s speech”.

So we may not have learned who supports academies in Wednesday’s PMQs, but we have learned one thing: the government intends to ignore professionals and the public, and plough ahead with plans to carve up a public service in order to hand chunks of it to its friends. Sound familiar?

Featured image via Sky News/Twitter (screengrab).