Culture Secretary John Whittingdale’s lengthy relationship with a dominatrix escort has been an ‘open secret‘ in Westminster and Fleet Street for some time. However, no major commercial paper had published a story about it until the Secretary was forced to reveal it himself on BBC Newsnight.

Over the last couple of weeks, the full story of this sex ‘scandal’ had begun to slowly turn heads after two pieces appeared on independent news sites. Not because of salacious tales about kink and fetish, but rather because they expose another story – a new revelation about the cosy ‘special’ relationship between politicians and the media post-Leveson.

James Cusick, describing himself as political correspondent for The Independent “until recently”, wrote an in-depth exposé for Open Democracy, in which he claims that several newspaper editors colluded to cover up the Whittingdale story. But Cusick is not too worried that the public ‘interest’ is without its sordid details. Rather that Whittingdale’s private life – known to several journalists and editors at some of the country’s top dailies – remained a secret for years because it created a bargaining chip that was in fact far more useful to them than hits and sales.

Cusick’s timeline of deceit and suppression says far more about media corruption than about the Secretary’s choice of sexual activity, and his claims potentially illuminate several more nails in the coffin for UK press freedom. Labour is calling for Whittingdale to “recuse” himself from being involved in any further decisions concerning media regulation.

Allegation, Allegation, Allegation

Cusick’s story is as follows. He and another senior journalist at The Independent worked for five months uncovering details about the Secretary’s relationship with an escort specialising in fetish and BDSM. The relationship lasted for at least a year, roughly from the end of 2013 to the beginning of 2015. Several papers were working on the story at various times, including The Sun, The Mail on Sunday and the Mirror Group’s Sunday People.

Eventually, Nick Mutch reported the story at independent news site Byline on April 1st.

Over a period of two years, writes Cusick, each group of journalists investigating the story was told by an editor to drop the story at the last minute. While Cusick claims that his sources in Fleet Street and Westminster are convinced of their political motives, editors’ official reasoning was either insubstantial or not given at all.

The Press Gazette has come to the defence of the tabloids saying that they also have an insider source, who claims that the real reason for the Whittingdale story being repeatedly dropped was:

- He is not married

- He does not appear to have broken the law

- He has not portrayed a false image

- He is not a figure who is high profile enough to ring many bells with readers

- The relationship apparently finished in any case before he became a Cabinet Minister (he was chair of the Commons culture select committee at the time).

However, one smoking gun in Cusick’s timeline is difficult to reconcile. Both Mutch and Cusick mention the Society of Editors Conference, at which Whittingdale gave a keynote speech:

The Editor of The Independent, Amol Rajan decided in October that he had made the decision to not run the story on ‘editorial grounds’. The previous day, Rajan had met with Whittingdale and Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre at the Society of Editors Conference in October 2015. When Whittingdale delivered his keynote address, he stated that he was minded not to implement a major recommendation of the Leveson inquiry and passed by Parliament as part of the Courts and Crimes Act.

Cusick claims that the very same editors, and Culture Secretary, who demand that journalistic freedom be protected at all costs, are colluding to suppress stories.

After the extent of the press’ widespread use of phone hacking was discovered – in the revelation that the News of the World hacked the voicemail of missing schoolgirl Milly Dowler, thereby compromising the police investigation – the Leveson Inquiry was launched. As well as taking testimony from phone hacking victims, and implicated editors and proprietors, the year-long investigation sought a clearer insight into “the culture, practice and ethics of the press.”

By ignoring the many recommendations made by Sir Brian Leveson in his report and the legislation subsequently passed in the House of Commons, both the press and the government are ensuring that the cosy and mutually-beneficial relationship between them remains strong as ever.

Conflicts of Interest

As Culture Secretary, Whittingdale is responsible for the legislation of the press. He held a decade-long position as chair of the Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport during the New Labour and coalition governments, and was previously Margaret Thatcher’s political secretary. Since assuming his cabinet position at the general election in May 2015, he has been responsible for:

- Planning to reform the board of the BBC by replacing executives with government appointees he will choose.

- Threatening to cut the BBC’s funding dramatically even after a deal was signed.

- Blocking cross-party legislation even after it was passed in the Commons to compensate victims of press intrusion.

- Supporting the press’ self-regulation body IPSO, which does not comply with the recommendations made by the Leveson Inquiry into the phone-hacking scandal and culture of the press.

Both Hacked Off and the Media Reform Coalition, organisations at the forefront of the campaign for media accountability, have written about the failures of IPSO and its toothlessness as a ‘watchdog’. One example of this was The Sun‘s infamous, and disproven, headline claiming that ‘1 in 5 Muslims sympathise with jihad’, which they were not required to retract, and IPSO even partly defended.

So papers signed up to IPSO had plenty to gain from keeping Whittingdale’s private life out of the papers. He was sympathetic to their cause, and their information could have been used against him if he wavered.

However, perhaps more troubling for Whittingdale than a sensationalised publication of his private life, would be the claims that he exposed himself and the government to blackmail and serious security risks. Mutch claims that his sources know the escort to have links to the criminal underworld, and that Whittingdale has been seen with her and other escorts inside the House of Commons during events, which:

raises serious questions [about] event security and Whittingdale’s judgment in bringing Ms. King to highly secure locations and events, and also with entrusting her with sensitive information. A senior Labour MP confirmed that he had seen Whittingdale with a prostitute at the House of Commons, although was unaware if it was Ms. King. When pressed on how he was aware of this, he told Byline that she was giving out business cards to other MP’s.

Our tabloid source drew a parallel to the Profumo scandal of 1962, where the Minister of War, John Profumo, was forced to resign after the revelation of his relationship with Christine Keeler, an escort who was also dating a Soviet attaché.

Both Mutch and Cusick’s articles display screenshots of internal emails from news offices about the story. They also detail that the MP travelled to the MTV Awards in Amsterdam with King, and failed to declare this in the Register of Members Interests. A lesser concern perhaps, but still questionable.

There’s also a potential conflict for Cusick. Describing himself as “until recently” a correspondent for The Independent, he hasn’t disclosed his reason for leaving the paper in his recent writing. The closure of the print version of The Independent could well have seen him made redundant, and potentially given him a motive to make false or exaggerated accusations. That doesn’t mean that these accusations are fabricated, however, nor does it mean that he didn’t quit because of the incident itself. Cusick was not available for comment at time of writing.

Reasonable Doubt

Cusick himself cites sources in Fleet Street and Westminster, some also involved in investigating the story, with conflicting accounts about why each paper’s investigation was dropped. Thus far no other journalists have formally come forward claiming that they were ordered to drop the story, however the level of detail of the account, screenshots of emails and what we know of press corruption already don’t bode well.

The Press Gazette‘s denial doesn’t appear that robust when compared with the detail provided by Cusick, but makes points that could well explain the lack of publication. However, many questions remain unanswered on all sides.

Editors Amol Rajan (The Independent) and Dominic Mohan (editor of The Sun at the time they were investigating), deputy editor of The Independent Dan Gledhill, the Mail on Sunday and the Mirror group have all been contacted for comment. None have replied. Similarly James Cusick has been unreachable, though The Canary contacted Open Democracy for comment from him also.

The Sun newspaper did respond, however only to say:

We have no comment.

A Post-Leveson World

The press have not changed their tune since the £5.5m Leveson Inquiry and its preceding scandal caused a public outcry. The recommendations resulting from the year-long inquiry have been largely ignored, and no change in media culture has been felt at all. This is an all too familiar setup: a public outcry, a moral outrage, a bandwagon of no-less-real frustration, then no action that makes any real change. Corruption is rife amongst the powerful, and this month plenty of it has been revealed in our current government already.

A particularly notable observation stands out. Cusick writes:

[Whittingdale] said his decision not to bring into effect a law voted through by parliament, which both he and the Prime Minister had previously acknowledged was an important incentive, didn’t mean he wasn’t ready to do so. He said the uncertainty kept the press “on their toes.”

When Whittingdale spoke to the Society of Editors last October he announced he had no immediate plans to sign into law any new financial penalties. He said he had listened to their concerns and would continue to review the matter.

The gathered editors and newspaper executives didn’t sound as though they were being kept on their toes. They burst into spontaneous applause.

Until more Britons join the growing campaigns to seriously challenge abuses of power, they will undoubtedly remain. Governmental procedure is apparently not enough.

Get involved!

Support independent media.

Write to your MP about press standards.

Get involved with the Media Reform Coalition.

Watch documentary about the press industry The Fourth Estate on YouTube.

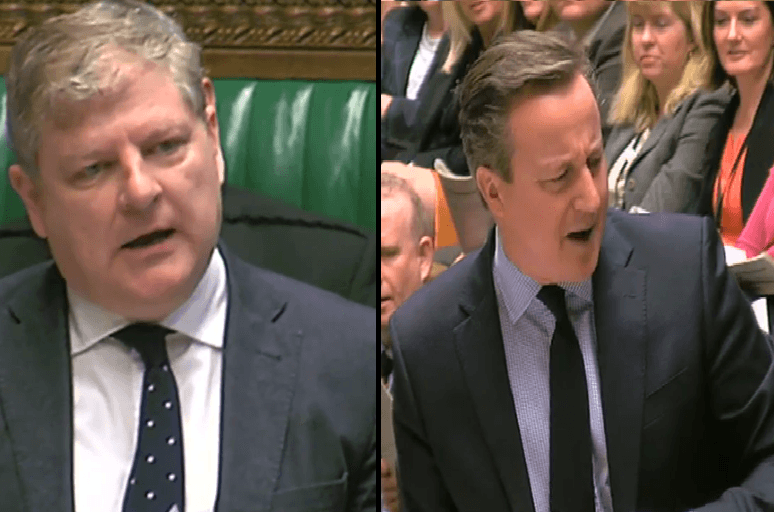

Image via BBC Newsnight