Following the terrorist attacks in Paris, a whole host of reactionary policies designed to stem the influx of refugees and migrants from the Middle East have been introduced across Europe, and particularly in the Balkans.

Serbia, Croatia and Macedonia drastically changed their border policies overnight and without prior notice, announcing that they would only accept refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. As a consequence, thousands of migrants and refugees from Morocco, Pakistan, Iran and other countries have been left completely stranded in border zones in the Balkans. A group of Iranian refugees has sewn their mouths shut in protest against these new policies, and a Bangladeshi migrant was seen carrying a sign that read “help us or kill us”.

This is the “undeserving migrant” rhetoric translated into action.

To put it bluntly, Europe has decided that someone is a refugee only if they come from a country that the West is – at least partly – responsible for screwing up.

Besides the fact that this is a very narrow understanding of what it means to be a refugee with no option but to escape, it doesn’t actually solve the humanitarian crisis in the Balkans. It is simply a continuation of Europe’s bankrupt migration policy, the same one that made people-smugglers rich by bringing into Europe hundreds of thousands of people along illegal and very dangerous routes.

Humanitarian organisations such as Amnesty International, the UN High Commission for Refugees and the International Rescue Committee, amongst others, have repeatedly stated that the most important thing is to enable the creation of safe and legal routes to and throughout Europe for refugees and migrants. In that way, we can dismantle the exploitative networks used by smugglers, and we also allow more effective and regulated controls.

These new policies are a move in the complete opposite direction. According to Amnesty International, they:

have resulted in large-scale renewed human rights violations, including collective expulsions and discrimination against individuals perceived to be economic migrants or refugees on the basis of their nationality.

John Dalhuisen, the Europe and Central Asia Director at Amnesty International, said:

These governments appear to have acted without thinking through the consequences for thousands of people who are now stranded in grossly inadequate conditions with nowhere to go and precious little humanitarian assistance.

This will only push those who are stranded back into the hands of smugglers.

With thousands more people on the way, action is urgently needed to reverse this worsening disaster.

Fear and fences

On 17 November, Amnesty International published a report called Fear and Fences: Europe’s Approach to Keeping Refugees at Bay. In this freely downloadable document, the international human rights charity makes a very simple, clear point: the Fortress Europe approach to migration is completely misguided, and has achieved the exact opposite of what it was supposed to.

The report states:

EU countries’ attempts to prevent irregular arrivals simply force refugees to more clandestine – and as a result mostly more dangerous – routes.

The comparably easier routes being closed off force refugees to take more difficult and dangerous journeys to reach safety in Europe; either over wide, fast-flowing rivers, or longer sea journeys.

The need to take complex and demanding journeys also makes refugees and migrants more and more dependent on smugglers. This puts them at the mercy of criminals, to whom they must pay high fees, which could have been used for integration purposes once in Europe.

Not only will these policies engender more illegal and dangerous migration, they also betray a prior agreement between the EU and the Balkan states, that was reached in late October 2015.

One of the conclusions reached at the meeting was that only a determined, collective cross-border approach to the refugee crisis can:

restore stability to the management of migration in the region, ease the pressure on the overstretched capacity of the countries most affected, and slow down the flows.

The only way to explain these new policies is by seeing them as part of the panicked politics of fear since the Paris attacks. The situation has not substantially changed since 13 November, the humanitarian crisis is as serious as before. The only thing that has changed is that now the possibility that terrorists could be infiltrating refugee routes has become the presupposition determining how we treat migrants and refugees.

The Paris watershed

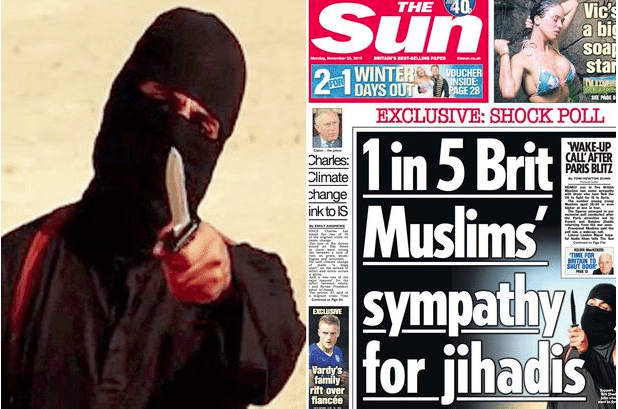

The brutal Paris massacre changed everything in the West. The terrorist threat posed by Daesh (Isis) was realised on an unprecedented scale in Paris on 13 November, as three simultaneous attacks left 129 dead, plunging France and Belgium into a state of emergency and triggering a new wave of Islamophobia and prejudice towards refugees. The Daily Mail’s infamous cartoon – published just days after the attack – is an obscene caricature that is all too reminiscent of Nazi Germany, but amongst European leaders several have made a link, if only implicitly, between refugees and terrorism.

When news emerged that Abdelhamid Abaaoud, one of the killers in Paris, had entered Europe via the same route taken by hundreds of thousands of refugees, the European leadership drastically changed their approach to the refugee crisis. However, as The Canary reported, all the terrorists that were identified in Paris were either French or Belgian nationals, not refugees. The attackers had an intimate knowledge of French society and knew where to hit.

Opting for more repressive policies against refugees is then no guarantee that there won’t be another 13 November. It seems more likely that the European leadership has used the Paris attacks as a convenient excuse to turn down asylum-seekers. Indeed, if previously there had been some semblance of European cooperation, as mediated by Angela Merkel, now the tone and the terminology used by most European leaders has completely changed.

The imminent threat of more terrorist attacks has made our government go into what Frankie Boyle calls “psychopathic autopilot“, and now the paranoid fear that Daesh fighters might be coming into Europe via the refugee route means that the fate of the thousands of refugees stuck in sub-zero temperatures is the last thing on our minds, in our media and in our policies.

On 20 November, the EU Justice and Home Affairs Council met for the first time since the Paris attacks to discuss new counter-terrorism measures. These include a whole barrage of new powers given to Frontex (the EU’s border police) and Interpol to carry out biometric controls (fingerprints, etc.) as well as tighter security checks on incoming refugees and migrants, but very little on how to effectively improve vital humanitarian provisions such as basic shelter and warmth.

Elsewhere in Europe, authorities have taken an aggressive stance towards refugees and volunteers, whilst still offering very little help to the informal assistance networks that are sometimes the only safety net for asylum-seekers in Europe.

On 24 November, Italian police carried out a raid at the Baobab centre in Rome, a refugee assistance centre that is entirely run by volunteers and that has provided basic services to 35,000 asylum-seekers this year alone, such as medical attention, legal support and practical advice on day-to-day matters. No terrorist was found, and instead, 23 people, including two minors, were taken into custody for not having proper documents. In a press release, the volunteers at Baobab wrote:

Is this the best answer we – a civilized country – can come up with in response to a “refugee crisis”?

Over the last months, volunteers like ourselves have tried our best to provide a dignified welcome to asylum-seekers. We have attempted time and time again to keep up a difficult relationship with the local government, but they have consistently threatened to close us down.

We have been asking for economic support, an appropriate and safe space to host migrants, and qualified and competent staff to work there.

None of this was given to us, and today we find ourselves in yet another unmanageable situation.

(Author’s translation from Italian)

Compared with the bullish and brash approach of European authorities, the actions of volunteers, aid workers and citizens – who continue to spend their time and energy helping refugees when no formal institution will – shows that a pragmatic solution is possible, if only our governments looked at the evidence with a level head.

Featured image via YouTube