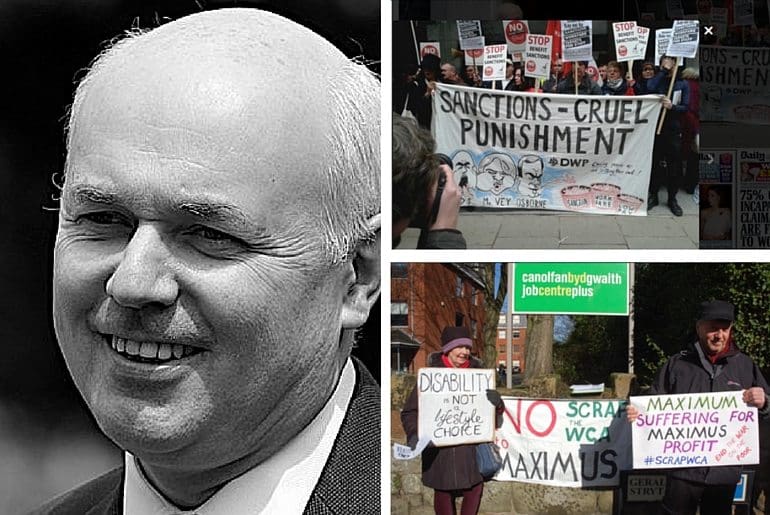

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent visit to the UK, like China’s Jinping and Egypt’s Sisi before him, has received criticism. One week before Modi’s arrival, a protest took place at the Houses of Parliament, likening Modi’s Hindu nationalism to Nazi ideology. Modi was in fact banned from engaging with the UK Government for ten years from 2002 due to his alleged complicity in the massacre of over 2,000 Muslims in the Gujarat province where he was Chief Minister.

Earlier this year, a parliamentary motion signed by 40 MPs including Jeremy Corbyn, John McDonnell and Alex Salmond called on David Cameron to bring up Modi’s human rights record during the visit. The motion raised several questions over Modi’s tendency to quietly suppress uncomfortable truths. Truths like the 2002 pogrom, the travel ban imposed on Greenpeace activists, and India’s out-and-out censorship of India’s Daughter – the BBC’s incendiary documentary on India’s extreme rape culture.

In Modi’s own country, scores of high-profile Indian intellectuals including Booker prize-winner Arundhati Roy returned their national awards in disgust at the mounting levels of communal violence that are being waged across India. Writing in the Indian Express, she explains her decision:

I want to make it clear that I am not returning this award because I am “shocked” by what is being called the “growing intolerance” being fostered by the present government.

First of all, “intolerance” is the wrong word to use for the lynching, shooting, burning and mass murder of fellow human beings. Second, we had plenty of advance notice of what lay in store for us — so I cannot claim to be shocked by what has happened after this government was enthusiastically voted into office with an overwhelming majority. Third, these horrific murders are only a symptom of a deeper malaise.

Life is hell for the living too. Whole populations — millions of Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims and Christians — are being forced to live in terror, unsure of when and from where the assault will come.

All these killings were made in the name of Hindutva, the BJP’s brand of Hindu nationalism that Modi has championed his entire life. So why is Cameron forging closer links with Modi?

Cameron’s long-term plan

Cameron is cosying up to the wrong people, and with four years left in his mandate, the worse is yet to come. Further cuts will be announced during the Autumn budget at the end of November, cuts that will affect once more the poorest in our society. Let us just hope that he doesn’t start taking Modi, Jinping or Sisi as his role models.

Narendra Modi’s 3-day visit to the UK was set to be a momentous occasion for Britain’s 1.5 million-strong Indian diaspora. Greeted with the best of British hospitality, the Prime Minister of India addressed 60,000 British Indians at Wembley Stadium; he had “luncheon” with the Queen, and he was the first Indian leader to address the House of Commons. His reception at Wembley Stadium, notes Keith Vaz in The Guardian, was paid for entirely by the diaspora, and as he points out, Modi’s visit was a historic event because “his arrival […] comes at a time when the British Indian diaspora has truly come of age”.

India has come a long way from the brutal exploitation it was subjected to under British colonial rule. Almost 70 years have passed since Jawaharlal Nehru was elected India’s first Prime Minister, and in that time India has flourished into one of the world’s emerging superpowers, whilst the British Empire crumbled. At this point in time, it is in Cameron’s best interest to secure a strong deal with India. For Modi? Not so much. His party, the BJP, has just lost a major regional election in the state of Bihar, and Modi will have bigger fish to fry when he gets home.

This is David Cameron’s latest official reception in the last few months. After meeting with China’s Xi Jinping and Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, this new trend is starting to show where Cameron’s priorities lie for his next term in government: strengthening Britain’s trade deals with emerging superpowers, and making sure that Britain stays relevant on the international stage. That China, Egypt and India all happen to be ruled by leaders with a penchant for authoritarianism is incidental. After all, human rights are no longer a “top priority” for the British government, according to Britain’s most senior Foreign Office official.

Modi’s human rights abuses are drops in the ocean for Cameron, considering that on so many more levels the Conservative party and the BJP actually have a lot in common. For one, both are on a path towards reshaping their respective countries, and not for the best.

Profits over people

The Conservative party’s neoliberal privatisation of pretty much anything that used to be public began in the 1980s under Thatcher. The process of privatisation and financialisation continued under Blair’s Labour leadership. In India this neoliberal project has also been in the works for decades, this time sponsored by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as a way to speed up capitalist development, and put India on the path of economic growth; the consequences in India have been disastrous, both for the environment and for the poorest in society.

One of Modi’s first big decisions as prime minister was to step up the privatisation of natural resources in India, particularly coal. While this was a boon for international investors including those in the UK, Modi pushed forward the bill on natural resources without consulting those who will be most affected. Sound familiar?

Adivasi tribes, a loose group of ethnic minorities on the subcontinent, have lived in mineral-rich areas for tens of thousands of years, and yet they have been classified by the Indian government as merely “occupying the surface of the land”. They have always been on the short end of the stick when it comes to owning the rights to their homeland, but with this year’s new legislation on natural resources they are once again completely excluded, all for the sake of big profits.

As far as the economic agenda is concerned, Modi and Cameron share a lot of common ground. But there is another, more sinister side to Modi, that we can only be grateful Cameron hasn’t taken on board (yet).

The violence of values

Since the election of the Conservative party this year, we have heard a lot coming from the likes of Theresa May about the importance of so-called British values, and we have been told time and time again that draconian measures are needed to keep us all safe from those who supposedly don’t share them – the enemy within.

This scare-mongering politics is affording more and more legitimacy to the idea that there is an impending threat to our national integrity. Muslims are the prime targets, but the UK’s anti-terrorism legislation has paved the way for an increased scrutiny into schools, universities, and even our own personal browsing activity. As Karma Nabulsi wrote in February:

Extremism is here described as ‘vocal or active opposition to British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs’. Yet even a cursory reading of the workings of this bill demonstrates that it goes against each of these goods.

It is against British values. It goes against the very meaning of democracy. It is completely against the rule of law and individual liberty. It flies in the face of mutual respect and tolerance.

This bill represents the rise of ideological extremism masquerading as British values. Every citizen needs to become informed about what this legislation will do, and how profoundly it affects them.

Directed against Britain’s cherished freedoms and its citizens, the bill itself is an extremist act.

Now take India. Modi’s time in government has seen the BJP turn into a heady cocktail of neoliberal orthodoxy and militant Hindu nationalism. This would be a concern for anyone who actually cares about upholding human rights, but for Cameron this obviously isn’t an issue. Why else would he entertain a “violent chauvinist” such as Modi? This was not just about big business, it was about a meeting of ideologies as well.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons