Boris Johnson has had to cancel appointments with at least three Palestinian officials, businesses and youth groups after he dismissed supporters of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement as “snaggle-toothed lefties.”

While addressing London tech firm representatives and international media, he slated the BDS movement, saying:

They are by and large lefty academics who have no real standing in the matter and I think are highly unlikely to be influential on Britain.

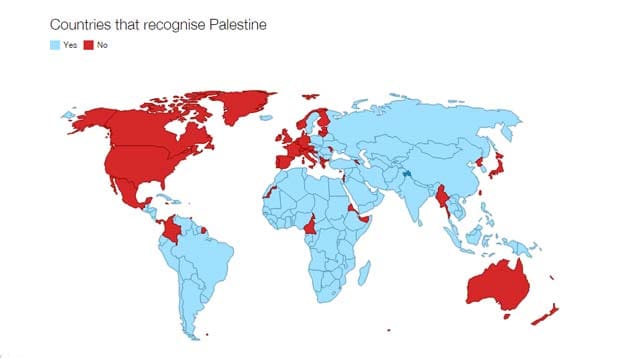

The remarks sparked outrage and condemnation, not least because they ignore the fact that BDS began in Palestine and enjoys widespread support both in the territories and worldwide. It has been effective at encouraging public institutions to withdraw investment from Israel, and academics to stop liaising with Israeli universities – this with the aim of putting pressure on the Israeli government to respect Palestinian rights and negotiate an acceptable peace agreement.

The remarks prompted the Sharek Youth Forum, who Johnson was scheduled to meet with in Gaza, to make the following statement:

As Palestinians and supporters of BDS, we cannot in good conscience host Johnson, as a person who denounces the international BDS movement and prioritises the feelings of wearers of ‘corduroy jackets’ over an entire nation under occupation.

The Forum also called the remarks “inaccurate, misinformed and disrespectful” and said “he consciously denies the reality of the occupation that continues to oppress them.”

It appears that the purpose of Johnson’s trip was to woo Israeli firms into investing in the UK, and that statements like these might be some sort of cack-handed attempt to win over Israeli investment, and discourage notions that the BDS movement will present any major obstacle to their profits:

I cannot think of anything more foolish than to say you want to have any kind of divestment or sanctions or boycott against a country that, when all is said and done, is the only democracy in the region, is the only place that has, in my view, a pluralist open society.

Sharek Youth Forum responded to these remarks with:

In Johnson’s own words, the ‘only democracy in the region … a pluralist, open society’ is one that oppresses citizens, confiscates land, demolishes homes, detains children and violates international humanitarian and human rights law on a daily basis.

Johnson did manage to meet with Rami Hamdallah, the President of Palestine, who, it should be noted, was elected democratically in what were considered internationally as “free and fair elections.”

The Palestinian Education Minister Dr Sabri Saydam cancelled his appointment, and the Palestinian territories’ first female governor, Laila Ghannam, also cancelled her meeting with Johnson, citing “personal reasons.” The Palestine Women’s Business Forum also backed out.

So far Johnson has not retracted his statements, saying they are in line with British policy. Indeed, the Palestinian government doesn’t officially support the boycott either, which is a considerably more diplomatic stance than Johnson has taken.

And while Palestinians are angry, British commentators have been equally unimpressed. Tim Shipman, political editor of the Sunday Times, suggested:

Boris Johnson has come out here trying to look like a statesman, and unfortunately he’s looked like someone who is not yet ready for that role.

We’ve been cosying up to oppressive regimes a lot recently, and it seems like Johnson has been trying to do with Israel what Osborne has been doing with China – namely, sending the message that no matter how bad their human rights abuses, Britain is open for business.

But in Boris’s myopic over-enthusiasm, the plan seems to have backfired.

Although there might be some glimmer of value in the notion that we have a better chance of pushing improvements abroad if we’re friendly trading partners with countries like China and Israel, that doesn’t seem to be the agenda, judging by sycophantic rhetoric of our wannabe statesmen.

Such an “all offers welcome” attitude to Britain’s economic partnerships is likely to have problematic long-term consequences. The major mechanisms that hold countries in check when it comes to aggression, whether it be against their neighbours, areas under occupation or their own people, are the threat of economic repercussions in the form of sanctions and boycotts, and a loss of influence on the world stage. If we tell regimes that whatever they do, we’ll still trade with them and support them, the world can only become a nastier, less free and more unstable place.

Image via Twitter.