Deaths in police custody have been an endemic problem in the UK for a long time, but are now at a five- year high, forcing the Home Secretary, Theresa May, to launch an independent review. This is necessary, but will be of little comfort to families already suffering those devastating losses.

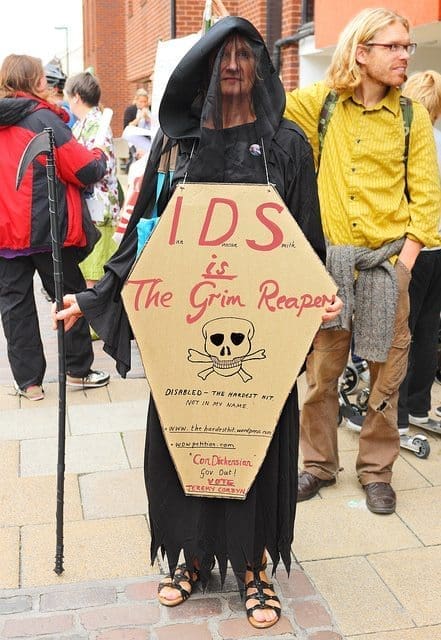

Deaths following state intervention are recorded in many ways, the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) reported 6,000 deaths between the year 2000 and 2010. One outcome these statistics all lead to is the failure to convict any police officer of wrongdoing in the resulting death or injury in the course of their duties. Many of these investigations follow similar lines; someone is arrested, they are held in custody, where they later become ill and subsequently die, as though some mysterious prison cell ‘Grim Reaper’ is at large in the holding cells of our country’s police stations. The announcement by Theresa May of a formal review follows a less-then-harmonious relationship between the government and police services up and down the UK – a relationship strained by reduced budgets and leadership since the coalition government started its austerity agenda in 2010. This masks a more serious issue for the families involved, namely that answers and justice continue to elude them.

Recent cases

Christopher Alder was a decorated former soldier of the Parachute Regiment who died in custody following arrest by Humberside Police on 1 April 1998. He choked to death, handcuffed on the custody floor. It was not until 2002, after considerable effort on the part of Christopher’s family, that five police officers eventually found themselves in court facing charges of manslaughter and misconduct in public office.

All were cleared.

Christopher’s sister, Janet Alder told The Canary:

I believe there is a resistance by the state to hold the police to account for a death in custody. The catalogue of deaths since 1969, with no accountability, is evidence of this. After an unlawful killing verdict, there is a battle to get the officers into court that the state resists at every step, the sheer contempt shown to many families (after a death in custody) is evident in Christopher’s case.

The scale of deception and obstruction by the state during the investigation in to Christopher Alder’s death is shocking and is reminiscent of the buried details now being divulged from the aftermath of the Hillsborough Disaster. In 2011, the UK government was forced to apologise to the Alder family, through the European Court of Human Rights on behalf of Humberside Police, for a failure to guarantee the right of life. But later that same year, Christopher’s family had to endure the stunning indignity of finding out that the body they had buried was not Christopher’s at all. It was the body of an elderly woman, Grace Kamara, who had been ‘mistakenly’ buried in Christopher’s place. Christopher’s body had been found in a mortuary, 11 years after the funeral.

Sean Rigg

Sean Rigg was 40 when he died after being detained by police in Brixton. He was a physically fit musician and artist who was dealing with a mental health issue, namely schizophrenia, and had been known to the local police as vulnerable for 20 years. Sean suffered a breakdown on August 21st 2008, and despite several calls from the support hostel he was staying in to the emergency services over a period of 3 hours, there was no intervention from the police, who refused to attend. Sean left the hostel and wandered through the streets, where a member of the public saw him in distress, making a fresh 999 call. The police responded this time and Sean was arrested at 7:40pm for a public order offence. Later, at the inquest, the jury found that, during the arrest, Sean was held in the prone position, face down with his hands cuffed behind his back, for at least 8 minutes. Eyewitness reports later confirmed that police were seen leaning on Sean’s head and neck throughout this time, pinning him down. This was in direct contradiction of initial police statements that claimed they restrained him in a matter of seconds, and with him lying on his side. Sean was bundled into a van and taken back to the police station, where he was left in the van for 11 minutes before being dumped, partially clothed, in the caged entry area of the custody suite. The police claimed that he was held there for ‘a rest’ before being processed. According to Sean’s sister, Marcia Rigg, it was really because Sean had been dying in the back of the van. Sean was pronounced dead some hours later.

The discrepancy between what was claimed and what was found by the investigations carried out by the IPCC and the Rigg family are striking, including the claim by police that there were no CCTV cameras in the caged area where Sean died. It was later conceded that there were cameras there after all, only they had mysteriously ‘stopped working’.

The death of Sean Rigg is a painful example of how people who suffer with mental health problems are treated like criminals by the justice system when they should be referred to hospital for care.

Bedfordshire Police

The death in custody of Leon Briggs at Luton Police Station occurred on November 4th 2013. The investigation into Leon’s death is now in its second year and Leon’s family are still no nearer to knowing exactly what happened, or why Leon died. The IPCC recently released a statement of apology for the delay in the report, only for the local Police & Crime Commissioner, Olly Martins, to say that the taxpayers deserved a swift resolution to the investigation to keep “costs at a minimum”. Five police officers and a custody sergeant are currently on suspension, pending criminal investigation and gross misconduct in public office. Leon was 39, physically fit and healthy, but also suffering with mental illness. Like Sean Rigg, police had been called in response to Leon’s behaviour and arrested him before taking him back to Luton Police Station. While the investigation report is yet to be published there is already evidence of conflicting versions of events. It was initially suggested that Leon had become ill at the police station before later dying at Luton and Dunstable Hospital. It was later proven that Leon did in fact die at the police station.

Since Leon’s death, a second death has occurred at Luton’s custody cells, a 25 year old man named Istiaq Yussuf, leading to calls for greater scrutiny into the practices being carried out by the Bedfordshire police force. This was further compounded when the family of Julian Cole, a 21 year old athlete, went public with the revelation that their son had his neck broken after being arrested by police in Bedford and has been left in a vegetative state. Once again the IPCC has been forced to apologise for the delay in releasing the final report into the assault that resulted in Julian receiving a ‘hangman’s’ fracture in his spinal column.

Of the Leon Briggs case, Janet Alder said:

Christopher was unlawfully killed by the Humberside police, his treatment being inhumane, degrading and racist. I see that two years after Leon’s death, the police are dealing in the same self-cloak of secrecy that compounds a families grief. Leon’s family have a right to answers. Leon, like many others, died in what we can only call barbaric unnatural circumstances.

Kingsley Burrell

Kingsley Burrell was arrested on March 27th 2011 after calling the police and claiming he had been threatened with a gun whilst out shopping in Birmingham. CCTV showed that no one had threatened him and he was arrested under the Mental Health Act. Kingsley was left handcuffed, face down, on the floor of Queen Elizabeth hospital for hours. He suffered a cardiac arrest. An inquest jury recently found that Kingsley was a victim of neglect after being let down by a series of police and medical workers as he lay prone on the hospital floor. Kingsley Burrell died of brain damage following a cardiac arrest. He was denied basic rights to life and treatment in an “obvious situation,” the jury stated.

Habib ‘Paps’ Ullah

Habib ‘Paps’ Ullah died 90 minutes after a stop-and-search by Thames Valley Police on 3 July 2008. A father of three, Habib ‘Paps’ Ullah, like many others to die in custody, developed breathing difficulties during his interaction with the police. He was later pronounced dead in hospital. Five police officers were accused of ‘breathtaking’ changes to their initial statements in relation to their interaction with Mr Ullah and were under disciplinary investigation for gross misconduct. All five were later cleared of any charges.

A never-ending pattern

Time and again, controversies arise over the handling of people in custody. We are told by politicians and senior police that ‘lessons are being learned’ and that police practices are being amended accordingly, yet we still see basic human rights to life being denied to people after interaction with the police, particularly in the case of mental health issues. This is compounded by a convoluted and delayed investigation process that seems geared to denying families access to justice. People caught wilfully withholding evidence or changing testimony are always cleared and no one is ultimately held accountable. If a member of the public found themselves in a situation where, as a result of their actions, someone was severely injured or died, they would have the full weight of the law applied to them. The same should apply to those charged with protecting us when they cross the line, if trust is to be returned to the public.

Without justice, there can be no peace. That is to say that the onus falls on us, the people, to force accountability for the actions taken that lead to such tragedies. Without the tenacity of the families directly involved in these cases, much of what we know would still remain in the shadows. Their perseverance is admirable, but they need our support if they are ultimately to succeed. It is said that time is a healer, but is not for those directly affected when justice is withheld. Our anger over these tragedies must not be diluted by the passing of time and we must support these families in their quest for answers and justice. The next such tragedy could affect any one of us. Should that happen, we shall want the precedent of police accountability on our side.

Featured image source: Richard Ashurst