Mental health is amongst the leading causes of ill health in the world, with 1 in 4 people suffering from a mental or neurological disorder at one time or another during their lives. Emergency service workers are twice as likely to suffer from these conditions than the general public.

Recent studies conducted by the mental health charity Mind have shown that 55% of participants had experienced some form of mental health issue during their careers, against 26% in the general workforce. Mind have subsequently launched a new initiative, the Blue Light Programme, to assist emergency service workers experiencing mental health problems and have been award LIBOR funding to progress their work.

Mental health is a silent killer of emergency service personnel the world over. In Australia, the Intentional Self Harm fact sheet showed that between 2002 and 2012, 110 emergency service personnel, from police, fire, and ambulance died by suicide. A recent request for statistics on UK emergency service personnel, found that they are not readily available from the Office for National Statistics, Home Office or Coroner’s Office. The failure to accurately record these statistics can be laid at the de-centralisation of information networks that once collated such data.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is not a mental illness reserved for the battlefield but can also be attributed to the numerous different types of trauma that our emergency services respond to daily. They live and work in communities that they serve and have families of their own. This can lead to them facing their own mortality when faced with a member of the public the same age as their own children or siblings or be faced with someone they know. Empathising with the people they serve is a part of who they are and can leave them exposed. PTSD can occur from attending one significant incident or following repeated exposure to trauma events. It can take days, weeks or even years for the PTSD to manifest fully.

The monitoring for this is not universally agreed and intervention is, therefore, lacking. Emergency service workers are notorious for bottling up issues, rather than discussing them, which compounds the problem. It is not unheard of for emergency service workers to self-medicate. Common signs of mental health issues surfacing include, excessive sleep, unplanned time off and the use of alcohol and drugs.

The latest incident attended is not always something that can be easily shared with loved ones, and they know that colleagues have their own difficult experiences to deal with.

Exposure to incidents is not the only factor in the increase in mental health issues in workers; increasing workloads, changing job roles, austerity and financial uncertainty have all contributed to mental health issues and the prevalence of PTSD in emergency service personnel as they battle the stressors of emergency response with everyday life. It has also been suggested that PTSD can be linked to burnout, caused by poor organisational leadership.

Emergency service workers are not superheroes, they are just people like you or I and sometimes need a hero of their own to ensure their mental health and wellbeing. The programme being run by Mind should be applauded and supported, just as our emergency services support us whenever we make the call.

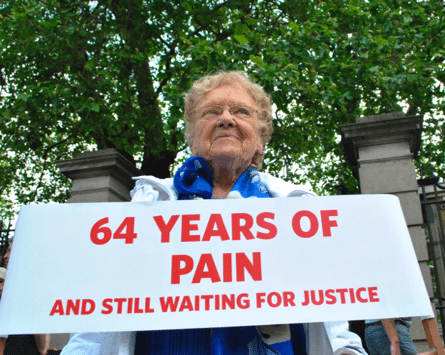

Featured images source: Wikicommons