In Kent, the Tories have given a grammar school permission to build an extension nine miles away. It seems the government could be trying to bring back selective schools by the back door. Educational experts, however, insist there’s no evidence suggesting such institutions are the path to success. What, then, is the best way to improve our education system?

Who is pushing the grammar school agenda?

With the approval of the Weald of Kent grammar school’s request to build an “extension” in Sevenoaks, The Guardian argues, the Conservative government has “set off another round in the long-running national debate about selective schools”, which nearly became extinct in the 1970s. Janet Daley, for example, has insisted that the “Left opposes selective education because it wants to stop the spread of aspirational middle-class values throughout society” (rather than because it is a divisive and elitist system). Conservative MP Graham Brady, meanwhile, has claimed the creation of more grammar schools would unleash “a new revolution of opportunity and social mobility for all”.

UKIP, meanwhile, complains that the Tories are not doing enough, and that grammar schools should be introduced “in every town and city” of the country. And it is followed closely behind by others with little knowledge of educational theory. According to Labour MP Lucy Powell, though, many areas were now “considering opening grammar schools” as a result of the decision in Kent – something she calls both a “backward step” and an “attempt to subvert the law”.

The reality about selective education

Even The Financial Times has insisted that grammar schools are “not the real issue”, and The Telegraph’s Jemima Lewis has claimed that a resurrection of such selective institutions would represent an act of nostalgic vandalism. She explains her view by emphasising that the increase in social mobility that occurred during the “golden age” of grammar schools was merely “a coincidence of timing” due to the post-WW2 boom in white-collar jobs.

Grammar schools may have given a better education to a minority of citizens, Lewis concedes, but the social benefits were simply “cancelled out by the consequences for those left behind”. Those who had failed to enter these institutes, for instance, were simply stored away in secondary modern schools “until they were old enough to get manual work”. In short, she says:

The last thing we need is a new wave of grammar schools sucking out the best teachers and brightest pupils [from the public education system].

The resurrection and destruction of old myths

According to The Guardian:

the social mobility argument for grammar schools has always been a myth.

Institute of Education (IoE) director Chris Husbands, for example, insists there is no evidence to prove that grammar schools improve social mobility. To back his argument up, he refers to IoE research published last year which showed there was no proof that more children were going to elite universities from grammar schools than from comprehensive schools. Furthermore, he emphasises that:

The best in-school predictor of long-term outcomes is quality of teaching. So all the obsession with structures, with grammar schools and secondary moderns and so on, is a complete red herring.

The University of Cambridge’s Anna Vignoles, meanwhile, asserts that evidence has shown that a child’s environment and parenting can actually be “more important than the school they attend” when we look at the lack of social mobility in Britain today. In other words, our education system does need improvement, but we also need to tackle the much bigger problem of widespread social injustice at the same time.

In spite of these arguments, however, Ed Dorrell at the TES says that:

The persistent, and wrong, idea that grammars aid social mobility and comprehensives stifle it just won’t go away.

Too many people, he insists, assume that working class children who went to grammar schools in the 1950s and 1960s did well precisely because of where they studied, while those who succeeded at comprehensive schools did so despite where they studied. This supposition, he says, is a big mistake. In reality:

grammar schools reinforced the social status quo.

Education workers in the UK, then, desperately need to counter the “irritatingly persistent argument” in favour of grammar schools, Dorrell argues. And to do so, they must argue the case of real alternatives. For if they don’t, people who have no clue about education will continue to impede progress with their false, simplistic arguments.

How can we really improve our education system?

The issue of class size often pops up as a key issue in the debate about improving education. Fewer students in the classroom, for example, means fewer discipline problems, less stress for teachers, and more individual attention for each student. In short, it seems like a no brainer.

However, we then need to ask ourselves why class-size reduction works in some cases but has a mixed or non-discernible impact in other settings and circumstances. At the same time, we also ought to evaluate why several countries in eastern Asia, where class sizes are higher than the global average, tend to perform so well. This phenomenon, says The New York Times, could be down to cultural differences, but could also be due to the fact that many students in these countries receive hours of additional instruction outside of the school environment.

When we look at Finland, which The Independent refers to as a “the by-word for a successful education system”, we soon realise that there is not one fix-all solution for improving education, and that real progress requires a number of different measures.

The main reason why Finns consistently beat all other countries as far as literacy and numeracy are concerned, though, is that teaching has become, according to The Guardian, “a highly prized profession” in their country. The idea is that teachers should have a Master’s in education and a real passion for the profession. And that is why primary education is the most competitive degree in Finland.

Once they are educational experts, teachers are given the autonomy to use their expertise however they see fit. They are trusted by parents and politicians alike, and are thus “free from external requirements” like inspections, standardised tests, and government interference.

At the same time, the aim in Finland was never to have the best qualified teachers hidden away in a handful of elite schools for only the most able children. Instead, asserts Finnish educationist Pasi Sahlberg, the “Finnish dream” was for children throughout the country to have a high-quality school in their own communities.

Finland has discovered that less is more

The Filling My Map blog summarises very well why we should listen to the Finns on education. In maths, for example, students around the world are trained how to solve complex equations. However, they find it much harder to apply what they have learned in a real-world context. In Finland, however, the focus is more on the practical application of knowledge. And no child is left behind. Basic mathematical understanding is a must for everyone.

At the same time, the blog says, Finland focuses on the idea that less is more. Firstly, formal schooling only starts at the age of seven, with younger children being allowed to “learn through playing and exploring” rather than being locked up in a stuffy classroom. From seven years onwards, children are considered “developmentally ready to learn and focus”. At the same time, the country recognises that research has consistently proven that “adolescents need quality sleep in the morning”, and that classes should therefore start no earlier than 9am.

Average Finnish teachers, meanwhile, teach only around 4 or fewer lessons a day, allowing them more time to prepare. At the same time, primary school teachers often have the same set of students for six years in a row, allowing them to become experts in the individual needs and learning styles of each pupil. Whilst giving the latter the adequate “consistency, care and individualized attention”, this system also allows teachers to “understand the curriculum in a holistic and linear way”.

Students in Finland, the blog emphasises, are encouraged not to do homework or exams, but to engage and participate more in their classes. They also have to sit around studying for less time, as educationalists are aware of the “several neurological advantages” of having numerous breaks and being physically active. “Stagnation of the body”, the blog says, “leads to stagnation of the brain”, which makes children lose their focus and become more restless.

Finally, students have to study fewer topics, but they do so in greater depth. In fact, Finnish schools have recently been undertaking a “radical education reform”, according to The Independent, which rejects the old idea of studying subjects. Instead, students will study “cross-subject topics”. EU studies, for example, will include historical, economic, linguistic, and geographical elements. And, in order to teach these topics, the experts will plan lessons together. Early studies suggest that the new method is improving student outcomes.

Let’s listen to the experts rather than the politicians

According to Helsinki University professor Leena Krokfors, the big problem with the British education system is that teaching only occurs “somewhere between administration and giving tests to students”. At the same time, private schools, free schools, and academies have been allowed to hire unqualified teachers ever since 2012, drawing significant criticism from unions like the NUT. These, Krokfors says, are the two main areas where Britain is going wrong. And they are areas in which politicians, who are not educational experts, have played a significant role.

How can we really improve our education system, then? Considering all we’ve seen above, I’m sure that teachers across Britain would join me in saying: let’s leave education to the experts.

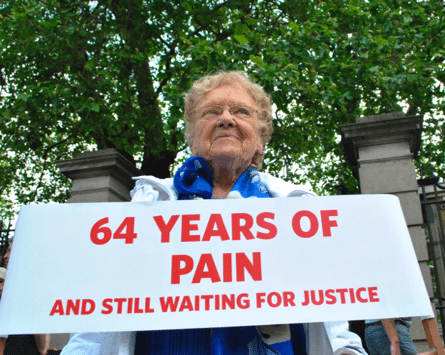

Featured image via Don Cload