For Palestinians the word Intifada is powerful and emotive. It literally translates as a ‘shaking off’, but means a civil uprising – be it peaceful or violent – by the masses against an occupier. In the modern era, the occupier they refer to is Israel, the ancient nation re-founded in 1948 on the land that had previously been the British-run ‘Mandatory Palestine‘.

Since that time, the territory has been governed as an official Jewish state. Hundreds of thousands of Arab natives were forcibly driven from their homes to make way for Jewish settlers, including a substantial influx of Europeans who had survived the Nazi Holocaust. The land was partitioned between the natives and the settlers, leading to much bitterness and frequent ongoing bloodshed.

As the decades have passed, Israel has increasingly encroached on the lands that were allotted to the Arab communities and neighbouring countries. These Occupied Territories have been the ‘theatre-of-Intifida‘, as Palestinians have risen up on two occasions since the late-1980’s to resist what they see, largely correctly, as a military conquest. The First Intifada from 1987 to 1993 was mainly peaceful, the Second, in 2000, was violent, but was met with crushing and unhesitating military force.

Throughout late September and October this year, the Occupied Territories have been shaking again due to what some are calling another Intifada. Palestinians took grave offence at restrictions being placed upon their access to the al-Aksa Mosque in Jerusalem by Israeli Security forces, while allowing Jewish groups increased access to the compound (a temporary ban on Jewish visits was imposed recently for the Islamic festival of Eid al-Adha). The mosque is the landmark of the Temple Mount-Haram al-Sharif compound, making it therefore one of Islam’s holiest sites, but also the single holiest site in all of Judaism. Hence, control of and access to it have remained frequent causes of friction between followers of the Abrahamic religions for many centuries, to the present day.

Whether a true Intifada or not, the current unrest has proven very difficult for Israel to contain, and it is possible that heavy-handedness by Israeli Security may be provoking more violence. At the time of writing, 43 Palestinians and 7 Israelis have been killed in the clashes since the start of October, and although the patterns of violence appear very haphazard and disorganised, they show no sign of abating. Tensions in East Jerusalem in particular remain unsettlingly high, and before the weekend the Palestinian President, Mahmoud Abbas, proposed that the United Nations should send a neutral international security force to police the al-Aksa compound.

The current Israeli Ambassador to the UN, Danny Danon, a notorious right-wing, anti-Arab, former committee chairman of Israel’s Likud Party, rejected the proposal before it could even be discussed in-session. The reason he gave for the rejection was that:

An international presence on the Temple Mount would violate the status quo of the last several decades … Israel does not think international intervention [in] the Temple Mount would be helpful or contribute to stability.

He added that the status quo was the best way “to keep stability in the region.” (By ‘status quo‘, he means the 1967 compromise of shared access to the al-Aksa compound by different faiths; Muslims are allowed to pray in the Mosque, while Jews may pray at the Wailing Wall.)

Danon’s remarks constitute an impertinent brand of ‘doublethink‘, for while discussing the fractious violence and instability that have plagued Israel/Palestine for decades while the status quo has been in place, Danon speaks of the status quo as a source of stability. The status quo may be a genuine attempt at fairness, at least superficially, but if it were a source of stability, there would have been no unrest to have triggered Friday’s session in the UN.

Quite simply, the status quo to which Danon refers is not presently working, and never has done. Therefore, changing it is to be encouraged, and a neutral international force of peace-keepers would not be any less fair an arrangement. It would not detract from the rights of either Jews or Muslims to visit al-Aksa, it would merely provide a policing force that does not owe allegiance to either ‘side’. At the moment, by contrast, Israeli Security forces are seen by the Palestinians as being pro-Jewish, and are thus one of the sources of friction. An international force may or may not lower tensions, but it can hardly be less effective than staying the present course.

Does Danon mean that he is worried that an outside security force would do a better job of keeping the peace, thus making Israel’s ‘get-tough’ approach look needless and incompetent? Does he perhaps worry what an outside securty force might discover about Israeli activities during the hostilities?

Perhaps both, perhaps neither, but it seems by his own words that Danon is opposed to any policy that might move events in a peaceful direction. With his infamous history of explicit hostility towards the Palestinians, this is perhaps unsurprising. While there is violence on the streets of the Occupied Territories, there is a pretext for more violence towards the Palestinians, and it is the sort of pretext he would not apologise for using to the fullest.

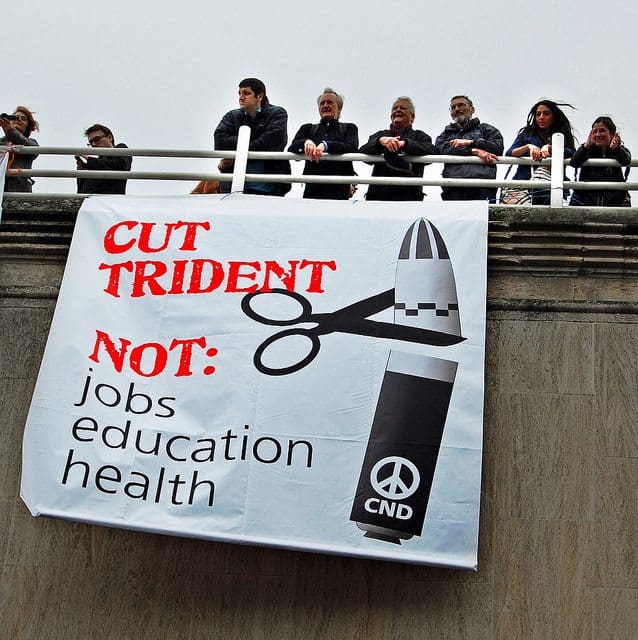

Featured image via Flickr Commons – Montecruz Foto