On 11 October at the Labour Conference, shadow health secretary Wes Streeting spoke of his party’s “ten-year plan for a National Care Service”. This was a key speech which happened merely days ago. So, you’d expect it would still be part of Labour’s agenda. Those who’ve followed the party under Keir Starmer, however, won’t be surprised to learn that the “ten-year plan for a National Care Service” is reportedly now a zero year plan for nothing:

In his Labour conference speech 4 days ago, Wes Streeting spoke about "our 10 year plan for a National Care Service"

Today, "The Observer understands that Starmer’s party will avoid laying out a detailed plan for reform of social care"https://t.co/yZP8cWYzdt

— Andrew Fisher (@FisherAndrew79) October 15, 2023

FFS

According to Sunday 15 October’s Observer:

Starmer’s party will avoid laying out a detailed plan for reform of social care, and the politically nightmarish issue of how to fund it, because it fears any proposals would be torpedoed by the Tories in the heat of a campaign.

According to senior party figures, Keir Starmer’s team – while committed to social care reform – do not want to offer the Tories a target that would invite them to attack the plans and make claims about the tax implications. Instead, there would be a general commitment to make changes when in office.

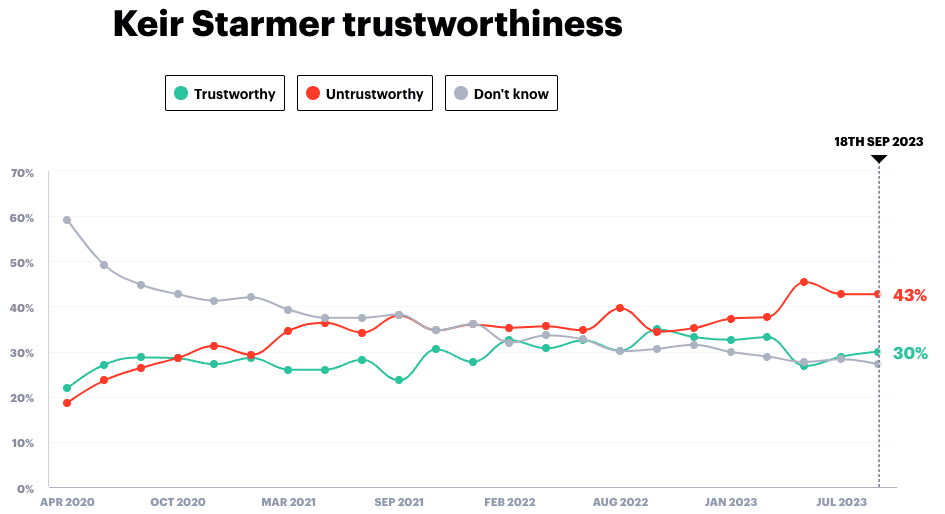

To sum up, Labour’s election plan is to offer vague promises from a man who the British public already don’t trust. This is polling from YouGov:

When Starmer first came to power, you can see the vast majority of people ‘didn’t know’ if he was trustworthy or not. 22% of those polled believed he was; 19% swung the opposite way. Over time, the ‘don’t knows’ have dropped as people have got to know the new Labour leader. However, while the number of people who trust him has risen 8 percentage points to 30%, the number who don’t trust him has risen by a whopping 24 percentage points to 43%.

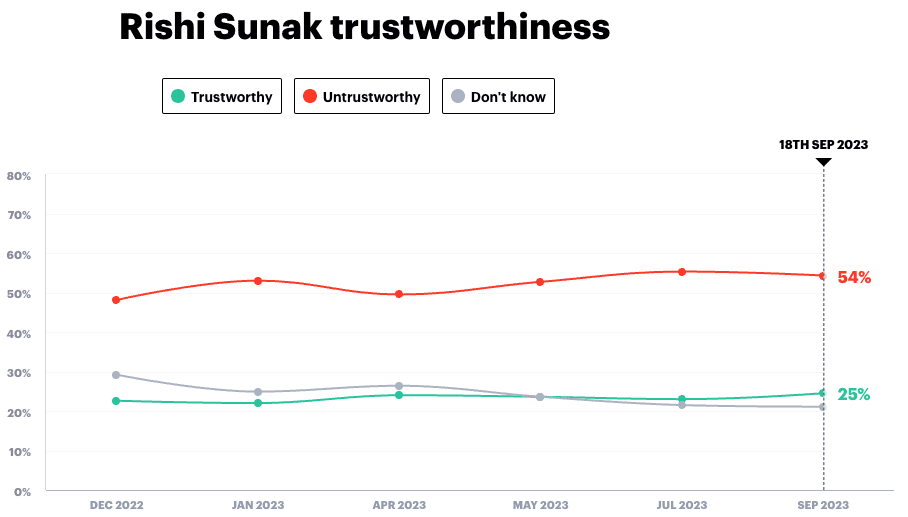

As you can see below, trust in Starmer is better than trust in Rishi Sunak, but it’s also less steady. Notably, the direction of travel for Starmer is that the longer people have any awareness of him, the less they trust him:

So, what’s happened to cause this situation? Quite simply, Starmer has shown himself to be a man who’s almost pathologically incapable of sticking to his word.

Mr U-turn

In June 2023, Politico compiled an already out-of-date list of Starmer’s key U-turns. Said list includes:

- Abandoning several proposals to renationalise key services (despite support for such policies remaining incredibly high).

- Un-abandoning his pledge to “end outsourcing” in the NHS.

- Distancing himself from the trade unions he once claimed to support.

- Abandoning his aim to retain EU free movement.

- Not only abandoning the pledge to remove Universal Credit, but having his work and pensions secretary claim they “actually agree with the concept behind” it.

- Abandoning the plan to abolish tuition fees.

- Ditch any serious pretence of fighting climate change.

- Abandoning his pledge to increase tax for the top 5% of earners.

- Scrapping his pledge to get rid of the undemocratic House of Lords.

This isn’t even all of it. And as such, it’s plain to see why you couldn’t trust this guy as far as you could throw him.

Electioneering

Of course, the lack of trust in Starmer may be baked into Labour’s strategy for the next election. If Starmer doesn’t offer anything, then people can’t mistrust his ability to deliver it. There are two problems with this, and the first relates to this quote from the Observer article:

“We need to give ourselves cover to do reform in the manifesto, without giving the Tories a target to attack us. We can’t allow the issue to dominate a campaign again,” said a party source.

Going off how eagerly Starmer sheds policies – especially half-decent ones – most people will naturally come to the conclusion that he isn’t abandoning progressive proposals because he’s a clever political operator; he’s abandoning them because he’s a regressive politician.

If Labour promised a National Care Service in ten years, people would constantly be asking for progress updates. By vaguely hinting at one, Starmer can more easily get away with not delivering a policy he had no interest in delivering in the first place. The embarrassing U-turns have taught Starmer one thing, it seems, and that’s that you can’t U-turn on a policy which never existed.

Social care: hardly a vote-loser

The issue is that people aren’t stupid, and many will see his vague promises for exactly what they are – i.e. a big old heap of nothing.

The second problem for Labour in the next election is this: what happens if the Tories find something they can offer which the public get on board with (much like when the Tories’ 2019 Brexit stance turned the party’s fortunes around)? This is from the Observer:

In 2010, Labour’s plans for funding social care were branded a “death tax” by the Tories, and hit the party’s vote badly, while in 2017 Theresa May’s Conservative campaign suffered irreparable damage amid accusations she was planning a “dementia tax”.

This framing is bizarre, as it suggests the concept of a National Care Service is a certified vote loser. The 2017 election isn’t a good example of that, however. While May was slated for her ‘dementia tax’, Labour offered a fully-funded National Care Service, and it saw the biggest increase in vote share since 1945. While Labour’s fortunes were down to more than offering a National Care Service, it’s clearly not the guaranteed vote loser that the party is now claiming it is.

Labour isn’t caring

While Labour claims it’s shaping its policy platform to win votes, I’d argue that we’re witnessing something else entirely.

The Tories’ 13-year failure to deliver has finally caught up with them, and polling is reflecting that. Starmer knows this is down to the Tories’ mistakes rather than his own moves. However, this window of time does give him the opportunity to abandon policies without it impacting on polling too much – i.e. he can make the argument that no one cared about these policies anyway. This is giving a false impression of what will happen in the actual election when all eyes are suddenly upon both parties, and it becomes more obvious than ever that Labour has nothing to offer.

At this point, it’s entirely likely that Labour win anyway because the Tories have even less to offer. Regardless of who wins in that situation, however, it’s the public who ultimately lose.

Featured image via the Labour Party – YouTube