An estimate from the United Nations (UN) shows that by the end of 2021, 377,000 people will have been killed during the war in Yemen. Around 150,000 people have been killed from the conflict, and many more have died from disease and hunger caused by the humanitarian crisis Yemen now faces.

Saudi Arabia has been leading a coalition that has been bombing Yemen since March 2015. The UK, however, has provided the supplies for much of this bombing. This choice to continue to supply weapons to Saudi Arabia in its campaign against Yemen has the same roots as the majority of Western-led involvement with conflicts in the area: oil.

How do we know that?

The Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT) released research in February 2022 which shows that the:

published value of UK arms licensed for export to the Saudi-led coalition since the bombing began in March 2015 is £8.4 billion (including £7.0 billion to Saudi Arabia alone) [our emphasis]

According to its own estimates, however, this figure jumps sharply:

CAAT estimates that the real value of arms to Saudi Arabia is over £20 billion, while the value of sales to the Coalition as a whole (including UAE and others) is over £22 billion. [our emphasis]

CAAT make it clear that the UK’s monetary support is vital to the ongoing Saudi presence in Yemen. Human Rights Watch has said:

armed conflict in Yemen has resulted in the largest humanitarian crisis in the world

CAAT have been given permission to proceed with a legal challenge to stop the UK government’s arms sales to Saudi Arabia. In a previous legal challenge, the Court of Appeal ruled that approving arms sales to Saudi was “‘irrational and therefore unlawful”. However, after a temporary suspension, arms sales have resumed with foreign secretary Lizz Truss claiming that violations of international law were “isolated incidents”.

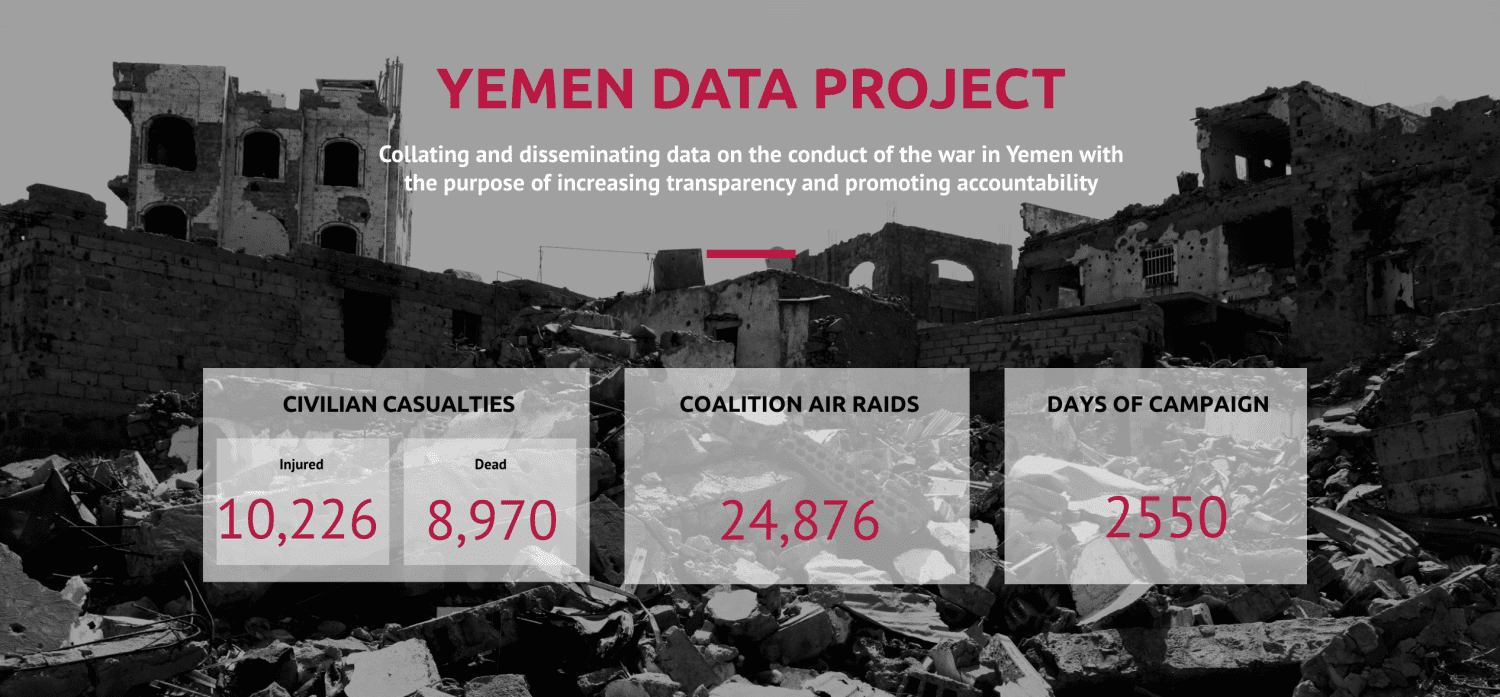

The Yemen Data Project has the following figures for casualties in Yemen (as of 18 March 2022):

Almost 25,000 air rids from the Saudi-led coalition is a catastrophically high number. The UK’s supply of weapons to the Saudis has facilitated these figures.

Greasy palms

Last week, Boris Johnson paid a visit to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The trip has been touted as an attempt to reduce the UK’s reliance on Russian oil. The Canary’s Joe Glenton reported on how Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s recent release from prison in Iran also bears the context of sanctions against Russia restricting oil supplies to the UK:

Russian oil is going to be less accessible as sanctions pile up following the Putin regime’s invasion of Ukraine. Other sources must be found. It follows that a thaw between the West and Iran is on the cards.

Johnson’s visit to Saudi Arabia is, then, part of a more general effort to remain in the good books of oil suppliers like Saudi Arabia, and Iran. Whilst Vladimir Putin’s horrific invasion of Ukraine is rightly condemned, Johnson seems to be happy to cosy up to Saudi Arabia and its government’s awful human rights records. Much like Zaghari-Ratcliffe was a pawn in geopolitical relations between the UK and Iran, so too are the people of Yemen made into pawns caught between the UK’s desire for oil and willingness to ignore morality when convenient.

Who will help?

March 2021 saw an update from the House of Commons library which summarises a significant cut in aid for Yemen. Initially, £160m was due to go to Yemen in 2020/21, but only 54% of that was actually announced in 2021 – a downgrade to £87 million.

At the time, the government admitted that it hadn’t even done an impact assessment on this decision.

Of course, Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine has also seen devastating and horrific loss. However, it is difficult to swallow the UK government’s support of Ukraine and its citizens as anything more than lip-service.

While it is wonderful that UK citizens want to open their homes to refugees from Ukraine, and are doing what they can to show solidarity, the story cannot end there. Expressions of solidarity are vitally necessary, but that solidarity shouldn’t ignore the Black, brown, Muslim, and otherwise marginalised communities whose blood is on the hands of the UK government.

One understanding of whether a country is at war might be a physical presence in an outside nation. That is an outdated and ineffective understanding. Modern warfare and the global market means that the UK is indeed at war, not just with Yemen, but also with other countries the UK is selling arms exports to. The UK has played an active role in the assaults on Yemen. To then cut whatever patchwork humanitarian aid may have been possible is monstrous beyond belief. The UK is at war with Yemen, has killed people in Yemen, has decisively contributed to the humanitarian crisis in Yemen – and Yemen can’t fight back.

The UK has blood on its hands, and its modern relations to countries like Yemen are a modern approach to coloniality: neocolonialism.

Featured image via screenshot/Evening Standard – cropped to 770×403