Update: This article was updated at 13.40 on 29 March to include post-publication comments provided by ZimParks.

The controversial sale of elephants from Zimbabwe to other countries, mostly China, is again in the spotlight. The renewed scrutiny comes due to author and filmmaker Karl Ammann highlighting related trading documents. They suggest there’s vast amounts of unaccounted for cash connected to the trades.

The attention comes at a bad time for China. The country is due to host a high profile biodiversity conference in May. These revelations will also do little to lessen criticism of Zimbabwe’s decision to capture wild elephants and sell them off to foreign zoos. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is unlikely to take pleasure in the scrutiny either. The global wildlife trading body oversees the system through which these elephant trades happen. Moreover, it’s already facing legal complaints over alleged violations of its rules.

Most of all, however, the fresh controversy is a further indictment of the wildlife trade. It’s an industry that has already proved to be devastating for humans and other animals. So the last thing it needs is further marks against its name.

The numbers don’t add up

Zimbabwe exported 32 young elephants to China in 2019. The sale caused an uproar as it happened amid legal action to halt the shipment. Zimbabwe also went ahead with the export just before CITES implemented a landmark rule change that would have made it near impossible to push through.

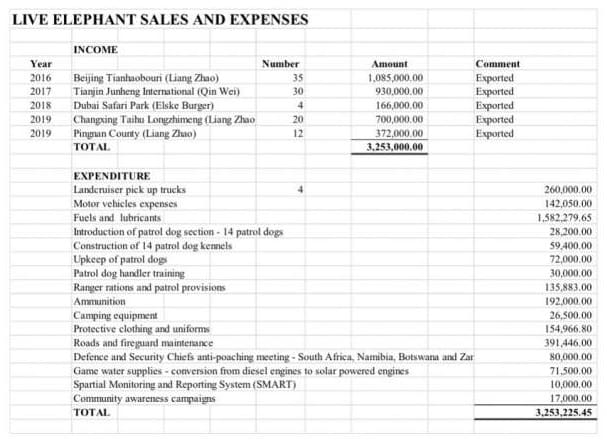

In response to the furore, the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks) released a list of elephant sales since 2016. On the list, ZimParks declared the income it earned from the elephants and what it spent the money on. It also named individuals in connection to the trades. ZimParks named Liang Zhao as being involved in the 2016 and 2019 trades. It named Qin Wei and Elske Burger in the 2017 and 2018 trades, respectively. Most of the sales were to venues in China, with one additionally to the UAE.

ZimParks declared an income per elephant of between $31k and $41.5k. But Ammann, who’s been investigating the international trade in elephants for years, has now brought attention to trading documents connected to the sales. They appear to show that some of the Chinese recipient venues declared a cost per elephant of around $125k.

That seems to be the case, for example, for both Longemont Animal World and Xiongsen Animal World. These venues received the elephants controversially sold in 2019, but ZimParks said the payment it received for the elephants going to those venues was $31k each. This means a discrepancy of $94k per elephant in those cases.

Duty-free imports

Ammann has further highlighted a document that shows China set “duty free import quotas for elephant, rhinos and pretty much everything else” in 2019. As such, he said, there would be “no need for a buyer to under or over declare the purchase price”.

Meanwhile, the filmmaker says a “well-informed animal dealer” in South Africa told him that there was a “$100,000 price tag” on the elephants Zimbabwe sold to Dubai Safari Park in 2018. But Zimbabwe said the payment for each elephant going there was $41.5k. So there’s a $58.5k discrepancy per elephant in that transaction.

What’s the problem?

A major concern in relation to these unaccounted for funds is that allegations of bribery and kickbacks abound within the CITES wildlife trading system. One current legal complaint in front of CITES, for example, involves allegations of corruption in Asian elephant trading between Laos and China. The UK law firm Advocates for Animals has raised this complaint with CITES on behalf of Ammann.

As The Canary previously reported, the legal complaint asserts that trafficking of elephants between the two countries “involved bribes with officials” in some cases. These bribes were allegedly sometimes connected with preparing the ‘paperwork’ for CITES permits. Within CITES, countries authorise trade through a permitting system.

In the case of the unaccounted for funds in Zimbabwe’s exports, Ammann says that “a range of players”, including brokers, could have cashed in via “kickbacks, bribes and commissions”. He alleges that “several sources” in China have told him that there are costs in the region “of US $160,000 per permit and per shipment” involved in international wildlife trading there.

The UK government lists the basic cost for a single CITES import and export permit as being less than £70.

Ammann’s investigations into elephant trading between Laos and China have shown similar price discrepancies to those apparent in the Zimbabwe to China trading. Although Chinese dealers may purchase a Laotian elephant for around $25k, the price Chinese zoos pay for them can be up to $500k.

So where’s the missing money?

The Canary contacted CITES about the price discrepancies in the Zimbabwe elephant trades. Among other things, we asked if the body had any knowledge of where the opaque money from these transactions could have gone. We also asked if the unaccounted for funds could have paid for associated costs of the trade. And, if so, who should have declared them – and where – under the CITES system. Of course, trading often involves associated costs. In this situation, for example, transporting the elephants from Zimbabwe to China would have cost money. CITES, however, declined to comment.

The Canary further contacted the Chinese CITES authorities and the country’s Endangered Species Scientific Commission. We asked about the unaccounted for funds and where associated costs should be recorded if they fall on the Chinese side of the transaction. We also asked about the country’s tax-free import quota. Specifically, we inquired whether the country takes steps to ensure such an incentive to import species doesn’t negatively impact those species’ conservation status in potential exporting countries. But they did not respond to The Canary either.

ZimParks’ response

The Canary contacted ZimParks too. Its spokesperson Tinashe Farawo said:

I am sure you are aware that Zimbabwe is under sanctions and not many countries are willing to deal with us especially from the West. Over the years there have been a lot of pressure from animal rights activists to stop the trade in wildlife products and elephant is no exception.

Farawo said ZimParks “does not receive funding from central government and we believe that the elephants must pay for their upkeep”. He argued that selling elephants “which we have successfully looked after over the years” was an option available to pay for resources for ZimParks personnel and their anti-poaching efforts. He added:

The ever increasing elephant population in this country is not an accident but a result of good management. As a country we deserve a pat on the back not these slaps.

Farawo further said that “elephants must benefit our people who are killed and injured daily”. He argued that human-wildlife conflict “has claimed more that 500 lives over the last 5 years” and continued:

We need our people to see these animals as an economic opportunity, we must build schools, clinics, roads from these resources.

Farawo also claimed that overpopulation of wildlife is an issue. Zimbabwe regularly argues that the country has an overpopulation of elephants which exceeds its carrying capacity. However, critics assert that “there is no such thing, scientifically, as ‘too many elephants'”. They say:

Animal populations self-regulate in relation to their food supply through births and deaths, or dispersal. There is no basis for a fixed ‘carrying capacity’ for elephants, except in the mind of man.

Elephant sales

We asked Farawo what role the named individuals had in the trades, such as animal traders or brokers. And we also asked whether the authority could explain the price discrepancy. Moreover, we raised an error in its list of elephant sales in 2017. It said ZimParks sold 30 elephants that year, whereas records show it in fact sold 38. The ZimParks spokesperson said:

In the spirit of transparency we told the world how many elephants we sold at what price and how much we received and what we did with the money.

He also asserted that “we are audited by the auditor general and we have never been found wanting since the new management under Dr Mangwanya took over in 2017”. Farawo continued:

the elephants were sold at $30k and we sold them to the buyers who were available and this excludes other costs such as capture, feeding the elephant, vet doctors services. No one was willing to buy our elephants at those prices you are telling us.

He said that “we were negotiating with the agents and we thought $31 000 was the best price because our gazette price to hunt an elephant in Zimbabwe is $10 000 so $31 000 to us was a fair price”.

Responsibility for the elephants

In our questions, The Canary further noted that four of the elephants sold in 2017 appear to have been subject to onward trading, as the documents Ammann highlighted showed. A tender announcement appears to show Ordos City Longsheng Wildlife Park purchased the four elephants from Tianjin Junheng International, in the same year that Tianjin Junheng International bought elephants from ZimParks. We asked the authority if it had assessed this onward trading venue’s suitability for the elephants. Farawo said that:

Before translocation of animals our ecologists visits the intended destination to check the appropriateness of the destination and all these things were done.

CITES secretary-general Ivonne Higuero has also previously said that a ZimParks veterinarian is sent with the elephants to China and stays with them for a month. Farawo further stated that Zimbabwe’s “ownership” of the elephants ends “at the airport” and that its:

responsibility with the agent ended when the elephants arrived safely to a destination and we have no obligation to control the movement of those animals in that country.

The ZimParks spokesperson asserted that the onward trading of some of the elephants “can only be a problem when they were using the Zimbabwean permits to move those elephants from one zoo to the other”.

Finally, Farawo said that “this was the first time Zimbabwe was selling elephants and without doubt we were at our weakest in terms of resources to fund conservation”.

Zimbabwe has, however, previously sold elephants to China in both 2012 and 2015. These exports were not included in the list it released in 2019.

Zimbabwe’s record

Zimbabwe had a score of 24/100 on Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index. ZimParks, for its part, has faced its fair share of corruption allegations. As a recent AllAfrica article noted, for example, some have accused its officials “of succumbing to coercion and bribery from powerful politicians and mining cartels” in relation to illegal gold digging in the country.

In 2015, environmental activists raised concerns over non-transparency and exploitation in the government’s elephant trading. Those concerns centred on the suspected involvement of a Chinese woman with Zimbabwean citizenship named Song Li. Having founded the Sino-Zim Wildlife Foundation, she appears to be heavily involved in wildlife initiatives in Zimbabwe. The foundation has reportedly donated to conservation efforts in the country, as has the Chinese government. China’s foreign affairs ministry has also provided assistance to a Chinese NGO called Blue Sky Rescue to conduct an anti-poaching programme in Zimbabwe. In short, the two countries have strong ties in relation to Zimbabwe’s wildlife sector.

In a 2015 article, Li admitted she had facilitated elephant trades between Zimbabwe and China. But she said she had earned nothing from it. A 2019 media report, meanwhile, claimed that a document named her as a facilitator in the 2016 trade. The Standard wrote:

Li reportedly facilitated the deal according to the first leaked ZimParks document whereas in the second document Liang Zhao was named as the facilitator.

Neither appropriate nor acceptable

The fact that these elephant sales are seemingly up to their neck in opaque cash isn’t the only issue though. There are numerous problems with the trades.

In a 2020 report, CITES members Niger and Burkina Faso accused Zimbabwe of contravening the Convention’s rules with the 2019 exports. Under the rules, Zimbabwe can only export elephants to ‘appropriate and acceptable destinations’ that are “suitably equipped to house and care” for them. In the report, the CITES members asserted that:

there is no publicly available evidence suggesting that the safari park in Shanghai [Longemont Animal World] which received the 32 young elephants from Zimbabwe in October 2019 –or any of the likely further destinations –can be considered as “suitably equipped to house and care for” live elephants

The report also noted that ZimParks officials and the chief inspector of the Zimbabwe National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ZNSPCA) had previously assessed eight Chinese venues in 2016, as ZimParks indicated in its 2019 comments. It explained that the inspectors “expressed concerns over the poor treatment and unacceptable facilities for elephants”. But the minister of environment authorised the exports nonetheless, the report said.

South African journalist Adam Cruise also pointed out to The Canary that none of these Chinese venues were “members of global zoo organisations like WAZA [World Association of Zoos and Aquariums]”. He said “that in itself is telling”.

Suffering “throughout their most likely significantly shortened lives”

Ammann has secured footage of 11 of the elephants in the 2019 export at their further destination, namely Xiongsen Animal World. In November 2020, The Canary sought an assessment of the footage from a number of wildlife experts. They included an elephant specialist with 37 years of experience. The experts concluded that the situation these elephants are in has caused a “dramatic negative change in their welfare”. That negative change is evident in heartbreaking signs of stress that they’re exhibiting. The experts said these elephants will suffer “throughout their most likely significantly shortened lives”. The overwhelming reaction of the experts was that Xiongsen isn’t an ‘appropriate or acceptable’ destination.

The trades have also faced hefty criticism for the brutality involved in abducting young elephants from their families. The young age of the elephants is also an area of controversy. Meanwhile, the scale of mortality in the trades is disturbing. Of eight young elephants exported in 2012, the 2020 report says seven are now dead or presumed dead. As of 2019, the remaining elephant was enduring a lonely existence in Taiyuan Zoo. He was in extremely inadequate conditions and had a history of poor health both mentally and physically. Meanwhile, the 2020 report said that of the 27 elephants Zimbabwe exported in 2015, 12 are now dead or presumed dead. The exact reasons for export-related deaths are often unclear. But injuries and illnesses sustained during capture, transport, and quarantine could have contributed to them.

The highest price

As The Canary has previously reported, the CITES system is full of holes that appear to be ripe for exploitation. The fact that huge sums of money may have disappeared through its cracks in relation to these trades is very concerning. It raises serious questions about the legality of these sales. Because an infraction of the domestic wildlife protection laws in the involved countries, such as those pertaining to corruption, could render the trades illegal under CITES’ rules. Right now, however, it appears few of those involved in the trades are willing to answer those questions. Clearly, though, the money isn’t just disappearing into thin air. There are apparently some winners in these less than transparent trades.

Exactly who those winners are may not be known yet, but we do know who isn’t coming out on top. The families of the abducted elephants aren’t, as they’re left bereft and traumatised by the loss of their young. Neither, of course, are the young elephants themselves. Ripped from their homes and loved ones, they’re now enduring an unnatural life in captivity. One that’s potentially filled with all the horrors – such as brutal training and demeaning performances – that such an existence can hold.

Featured image via Karl Ammann