Disabled People of Colour are being left out of conversations on disability rights. It’s happening in government reports and even in reports from charities. Experiences of ableism are not separate from experiences of racism. And disabled People of Colour don’t experience ableism or racism in turns, only one at a time. Other factors often complicate things too. It’s time we worked to bring these issues forward.

What we’re doing

The Canary’s investigations unit uncovers, among other things, stories about communities organising amongst themselves. These communities are forced to act for themselves when the establishment has marginalised or forgotten them. At The Canary, we’ll continue to ensure that we shine a light on grassroots organisations that are run by marginalised people.

We’ve already covered the work of activist group We Can’t Consent to This in our ongoing investigation into the rough sex defence. Now, we’re building the series with an investigation into a range of issues concerning disabled People of Colour.

Disabled people already face awful situations. These include cruel policy decisions from the DWP, dehumanising PIP assessments, and high levels of poverty.

However, as is all too often the case, People of Colour are in a position where class, race, sexuality, and gender severely complicate our experiences of ableism. This series will look at how disabled People of Colour have been abandoned. Then, we’ll turn to the grassroots organisations that are actually working for disabled People of Colour. We’ll be speaking to some of these people as we look at the range of issues at play here.

What data is available?

Office of National Statistics

The Office of National Statistics (ONS) has released a couple of reports that relate to coronavirus (Covid-19). One of these reports looks at death rates in relation to disability, and the other one looks at death rates in relation to ethnicity. Given that both of these categories have seen higher death rates during the pandemic, this research is important. But, in not looking at the intersection of ethnicity and disability, where does that leave disabled People of Colour?

The report on disability concludes that almost 59% of all coronavirus deaths during 2 March to 14 July were of disabled people. The report on ethnicity concludes that most People of Colour were at a greater risk of dying from coronavirus than white people. Putting these two bits of data together, it’s possible to assume that disabled People of Colour are at a greater risk of dying from coronavirus.

But that’s the thing. We shouldn’t have to assume.

The ONS has extensively covered disability in the UK. This includes reports on disability and education, disability and employment, and disability and loneliness. This is vital. We need to consider disability from lots of angles if we’re going to be able to work out how to help disabled people best. But disabled People of Colour also deserve help. They can’t be helped if organisations aren’t seeing where and how these problems overlap.

In 2019, the ONS published an article discussing how to improve its own disability research. It stated that it needs to expand its topic areas. And specifically, it stated that a report from the UN said more data was needed on “disabled people from black and minority ethnic groups”. So, by its own admission, this is an area that really needs some extra attention.

Government data

Meanwhile, the government has a list of disability-related facts and figures up on its website – from 2014. This six year old information doesn’t have a dedicated section for disability and ethnicity. It does direct us to the Family Resources Survey, which was last updated in March 2020.

This survey also doesn’t mention ethnicity in relation to disability. But it does say:

The prevalence of people reporting a disability varied across the UK. The North East had the highest percentage of people reporting a disability in 2018/19; 28 per cent (0.7 million people). The percentage of people reporting a disability was higher than the UK national average in Wales (25 per cent), Scotland (24 per cent), and Northern Ireland (23 per cent). In contrast, London had the lowest percentage, 13 per cent, of people reporting a disability (1.2 million people), followed by the South East, with 19 per cent (1.7 million people).

Using the same strategy as the ONS data, we can make some connections here. If the North East had the highest percentage of people with a disability in 2018/19, we can take a look at the Indices of Deprivation from 2019. This is a piece of research which tracks poverty in England.

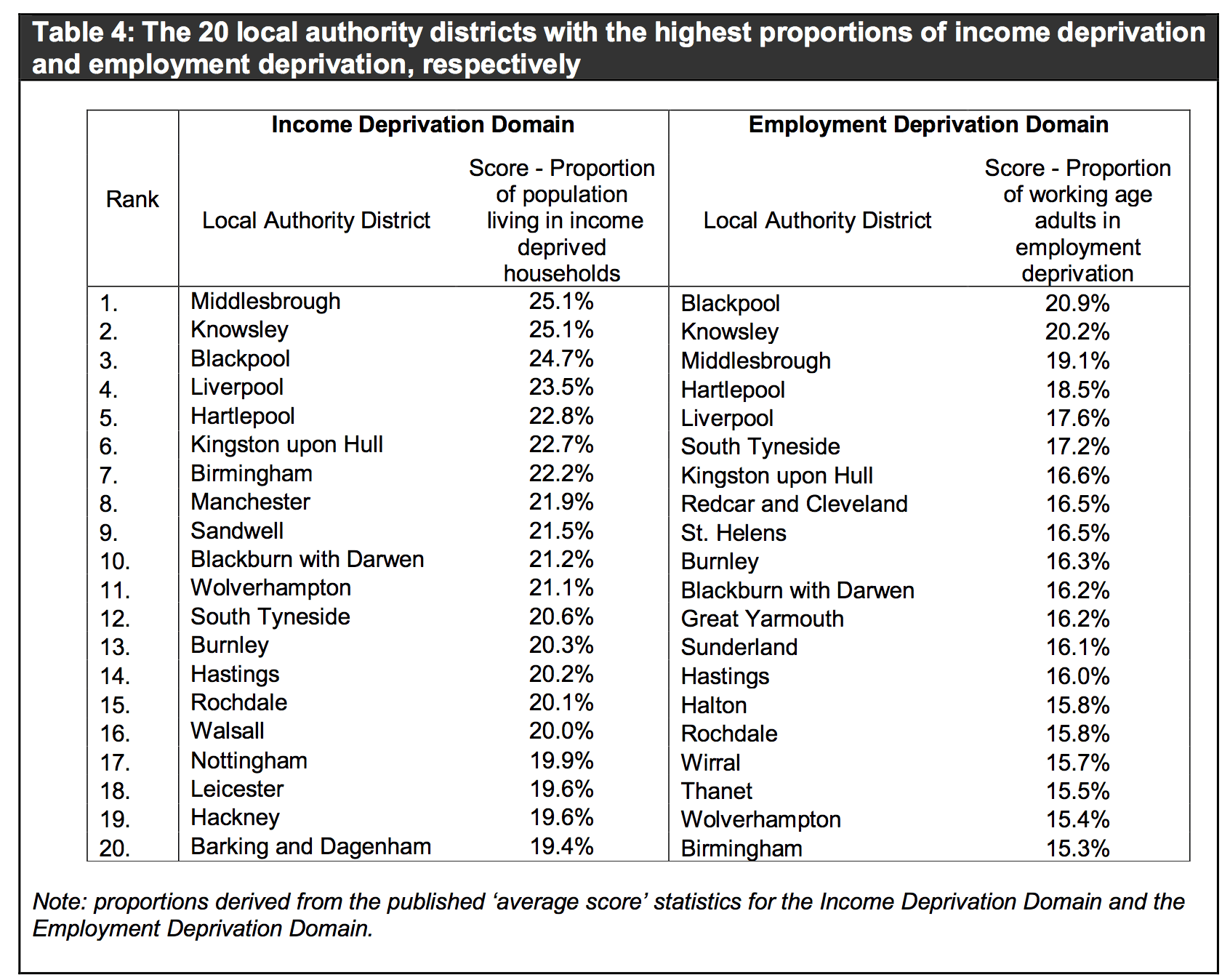

Below is a table from the indices (18) which lists areas in England with the highest rates of income and employment deprivation:

Areas in the North East include Middlesborough and South Tyneside. Given the struggle with income and employment in these areas, we can safely ask: what does this mean for disabled people in the North East?

Papworth Trust

To help answer this question, we can turn to a report from the Papworth Trust. The trust published a report in 2018 which looks at disability in relation to employment, social care, and housing.

In terms of class, the report notes that:

Full-time disabled workers earn on average 12.6% less (£75 a week) than full-time non-disabled people.

For gender, it reports that there are more disabled women than men. It also found that disabled people are twice as likely to be unemployed as abled people.

Importantly, the trust actually has a discrete section for ethnicity. It found that:

Research shows that when people from black minority ethnic communities have health or social care needs, they are more likely than other people to have difficulty finding and using appropriate services, and are more likely to experience poor outcomes.

Finally, there’s a clear link made between disability and minority ethnic communities. The implications for this are huge. Because charities and institutions deciding how resources are divided need to be able to see where help is needed most.

The trust’s report shows that there’s a link between poverty and disability – but also ethnicity.

Ethnicity exacerbates problems of class and disability. And charities and institutions have a duty to pay attention to people caught in this bind. These issues are not experienced singularly. They combine and intersect in harmful ways. For people living in the North East, to use the example above, there could be much to face:

- Higher rates of unemployment and wage gaps for People of Colour.

- Higher rates of unemployment and wage gaps for disabled people.

- Higher rates of unemployment and wage gaps in the local area.

So if disabled People of Colour are living in deprived areas, as is likely, they’ll need specific and targeted support. We shouldn’t have to cobble together bits of data in order to make these connections. That itself is, however, part of the violence of white supremacy. It will keep you explaining and accounting for yourself.

The problem with absence in policy

I myself am a disabled Person of Colour. And I therefore strongly feel that we shouldn’t have to cobble together bits of data in order to highlight our compounded struggles. I don’t need research on myself and my communities in order to learn about myself. But I do need research that makes sure it works to see people like me, and to make sure that we have access to the support that we need.

Intersectionality is not a buzzword or a trend. It is a practice. It can change people’s lives if used effectively.

Next, the series will speak to people involved in grassroots campaigns for disabled People of Colour.

Featured image via Unsplash/Womanizer WOW Tech