On both sides of the Atlantic major retail clothing chains have been struggling in the midst of coronavirus-related (Covid-19) shutdown measures. Economic commentators have been fretting about the potential fallout. Yet, although the inevitable loss of jobs is regrettable, we shouldn’t mourn the decline of these ‘fast fashion’ giants. In many respects, they represent all that is wrong and destructive about unfettered corporate globalization.

Bankruptcies and administration on both sides of the Atlantic

On 4 May, the major US clothing retailer J. Crew – a familiar sight at malls across North America known for the ‘preppy’ style of its wares – filed for ‘chapter 11’ bankruptcy. A matter of days later, another major US clothing retail company, the department store chain Neiman Marcus, also filed for bankruptcy protection and moved to “shutter all 43 of its stores and furlough most of its 14,000 workers”.

The UK has seen a similar story play out. On 9 April, the Retail Gazette reported that Debenhams will go into administration. Then in May the BBC reported that 15 of its locations will not reopen after the lifting of coronavirus-related lockdown measures. Later that month, fellow clothing retailers Oasis and Warehouse also went into administration, leading to over 2,000 employees either getting furloughed or laid off.

Something we should welcome?

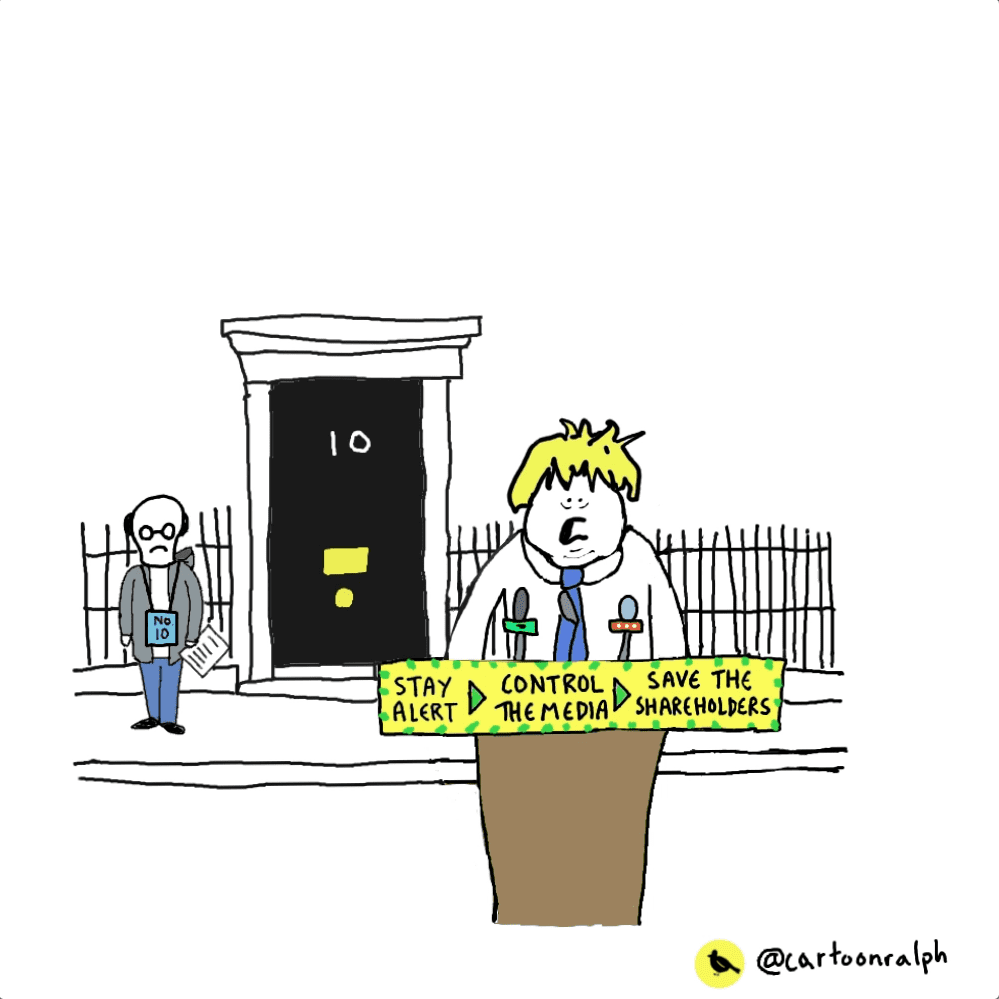

These job losses are indeed troubling – especially given that the right-wing faux-populists who currently occupy the White House and 10 Downing Street are unlikely to provide much in the way of support. But in other respects, the demise of these retail giants ultimately ought to be welcomed. Because the modern fashion industry has become an expression of all the worst things about economic globalization, from worker exploitation to excessive consumer waste.

As US journalist Elizabeth Cline puts it in her 2012 book Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion:

fashion largely deserves its bad reputation. It’s now a powerful, trillion-dollar global industry that has too much influence over our pocketbooks, self-image, and storage spaces. It behaves with embarrassingly little regard for the environment or human rights. It changes the rules of what we’re supposed to wear constantly, and we seem to have lost our sense of self along with changing trends.

Sweatshop labor and wasteful overproduction

Cline documents how ‘fast fashion’ clothing companies outsourced their production to factories in the developing world in order to drive down costs. As a result, many of their products are now made in far-away sweatshops in which people often work for a pittance in gruelling, unsafe conditions. These (overwhelmingly female) workers are, furthermore, usually offered few worker protections and seldom have unions to represent their interests. In the process, this decimated the once-thriving US domestic garment industry, which (unlike ‘fast fashion’ companies) employed well-compensated workers.

Cline also investigated the huge amount of clothing waste that results from this system in a chapter called ‘The Afterlife of Cheap Clothes’. She describes how used clothing which doesn’t end up in landfills often finds its way to clothing recycling depots. These places have become increasingly overwhelmed by the influx of (often barely worn) clothing discarded by consumers as they constantly update their wardrobes to keep up with the latest fashions. Much used clothing also makes it to developing countries, which are now themselves overburdened by the constant supply.

Looking to the past and to the future for inspiration

Many of the trends Cline describes are, in fact, fairly recent developments. Not so long ago, clothes were made to last as long as possible. As a result, people bought less (and often second-hand) but higher quality clothing – and so tended to dress better too. People cared for what they had and repaired damaged garments. But in today’s profit-obsessed market, all this has fallen by the wayside since selling ‘fast fashion’ more often is more profitable.

Cline urges ethically-conscious consumers to shop responsibly by buying second-hand when possible and searching out quality, well-made garments that will last. But to push back against the tide of ‘fast fashion’, structural, societal, and economic change will also be necessary. As The Canary has previously argued, the coronavirus outbreak has provided an opportunity to re-evaluate what humanity really needs in order to be fulfilled. The decline of these corporate retailers might end up forming part of that process.

Featured image via Flickr – Ryan McKnight