As Boris Johnson tries to shut down parliament to push through Brexit, he continues to maintain there’ll be no Irish backstop. And at least one British mainland police force is being readied to patrol the streets in the north of Ireland in case of escalating violence or civil unrest. They would join several hundred intelligence officers already stationed there.

Reinforcements

Up to 300 police officers from Scotland are to be relocated to the north of Ireland should violence there escalate because of Brexit. And more could be drafted from the Metropolitan Police.

Scottish Policing Federation general secretary Calum Steele said:

The reintroduction of the tactic of deliberately targeting officers and laying booby-trap bombs, or bombing locations where they are going to be, changes the dynamic significantly.

This year alone I think there has been five attempts on the lives of police officers in Northern Ireland, you have only got to look at the recent bombing attempts in Fermanagh and Armagh to see that activity is becoming more prevalent.

Earlier this year, it was reported that 700 MI5 officers were already in the north of Ireland to deal with any Brexit-related unrest.

Paramilitary warnings

In 2019 alone, attacks in the north by or attributed to republican paramilitaries included:

-

- August: a hoax bomb was found near Wattlebridge (Fermanagh); it was believed to have been planted to lure police to Cavan Road, where a second but real bomb was found.

- July: a device exploded at Tullygally Road, County Armagh, again apparently to lure police to the area.

- June: a bomb was found under a police officer’s car at an east Belfast golf club.

- May: police were attacked with petrol bombs outside a polling station in Derry.

- April: journalist Lyra McKee was murdered during a riot in Derry.

- March: letter bombs were posted to five locations, with all but one targeted to recipients on the British mainland.

- January: a bomb exploded outside a courthouse in Derry.

While Brexit dominates the UK media, paramilitary violence in the north of Ireland hardly gets a mention. Indeed, as journalist Ben Kelly said:

A bomb attack on police anywhere else in the UK would have dominated the news – but the Fermanagh incident barely registered.

Army/police warnings

Simon Byrne, chief constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, has expressed concern for what would happen should the backstop be dropped. He warned of escalating violence if a ‘no-deal’ Brexit proceeds.

Former army officer Nicholas Mazzei, meanwhile, said:

A hard border splitting the two nations will bring all the dissidents back (with lots of weapons and explosives they didn’t declare) and mainland police are not geared up for it. [Police Service of Northern Ireland] officers carry handguns; GB police do not unless they are specialists. This is a very, very precarious situation and is likely to lead to the deaths of police officers. Let’s not forget; many police will be needed in GB due to civil unrest here.

Lawmakers’ demands

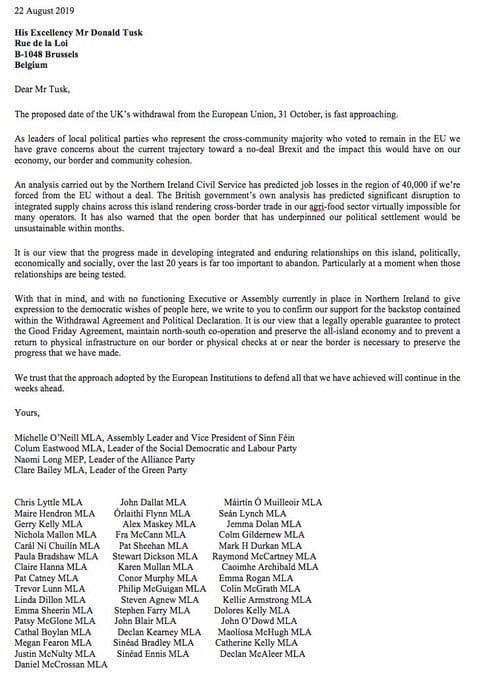

Meanwhile, 50 Sinn Féin (SF), SDLP, Alliance, and Green Party lawmakers have written to Donald Tusk, president of the European Council, affirming support for the backstop:

55.8% of the EU referendum voters in the north of Ireland voted against Brexit.

In 2016, SF proposed a solution to Brexit. It proposed that the north should receive special status, with the whole of Ireland to remain within the EU. And it clarified:

The prospect of the North being removed from the EU against the will of the people, and the return of a hard border in Ireland, has brought the issue of Irish re-unification firmly back onto the political agenda.

Ignoring history

Johnson’s decision to send in British police to the north of Ireland to deal with unrest or violence as a result of Brexit has echoes of another time. 50 years ago, in 1969, a similar decision saw British troops (under ‘Operation Banner’) being assigned a ‘peace keeping’ role on the streets of Belfast.

But their presence was not universally welcomed.

In August 1971, over three days, 600 British soldiers raided houses in a Belfast suburb. 11 unarmed civilians were murdered by members of the Parachute Regiment in the Ballymurphy Massacre. The following year, on 30 January 1972, a civil rights march of 10,000 in Derry saw at least 13 civilians shot dead by members of the Parachute Regiment; this was Bloody Sunday.

These were only two incidents of many in Britain’s ‘Dirty War’ in the north of Ireland.

Almost 30 years later, the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) was signed, leading to relative peace in the north of Ireland. But by preparing to send British police to the north of Ireland, Johnson is adopting a dangerous strategy. For if there’s no backstop, only one customs officer or police officer at a border crossing needs to be attacked for there to be more tragedies. And Johnson must bear some of the responsibility.

The choice is clear

Johnson’s cavalier approach on Brexit could provoke widespread protests on the streets of the British mainland too, according to people like journalist Paul Mason.

The choice is now clear: the politics of xenophobia, division, and rampant capitalism; or a fairer and more just society for all. And Ireland could well play a key role in this fight.

Featured image via screenshot