It can often feel as if digital technology giants like Google and Facebook get a completely free pass from governments around the world. In particular, their role in decimating the increasingly beleaguered media industry has largely gone unchallenged by governing parties of both the right and the left. But now, two nations on opposite sides of the globe have finally taken an important first step in addressing this problem.

An initially ignored report leads to bold action

In June 2019, Australia’s Competition and Consumer Commission released a report that investigated anti-competitive practices on the part of big tech companies. In addition to recommending more action on users’ right to know about how their data is being used, the report condemned these companies’ role in decimating the news industry. It pointed, in particular, to the quasi-monopolistic role played by Google and Facebook, and the way they publish content from news organizations without paying them anything for it.

Paradoxically, the report failed to garner significant attention in the Western press at the time. But earlier this month, the New York Times reported that the Australian government is beginning to take action against the practice. In April, it instructed its national regulator to make digital platforms negotiate payment for posted content that was originally produced by news organizations. A government spokesperson said:

The digital platforms need media generally, but not any particular media company, so there is an acute bargaining imbalance in favor of the platforms. This creates a significant market failure which harms journalism and so, society.

Shortly afterward, regulators in France enacted a similar measure that will force Google to devise a system to pay news publishers. The French government has also begun to pressure the European Commission to change its copyright law accordingly, which opens the possibility of a European Union-wide standard based on the French model. And there are signs that other countries might soon follow suit, with leaders in the Republic of Ireland and Malaysia expressing interest in similar laws.

Challenging an entrenched narrative

These developments provide a glimmer of hope that media organizations might enjoy a more secure future. But additionally, they also challenge the widely-held view that the financial woes suffered by news organizations are simply an inevitability of the digital age. According to this narrative, the lay-offs, closures, and financial difficulties amongst those media organizations that do survive have resulted from the fact that readers can now get news for free online. This is, in fact, (at best) an oversimplification.

Before the internet existed, the vast majority of newspapers’ revenue came from advertising, not the money people paid to buy physical paper copies. But as news transitioned online, newspapers (of which there were many) lost their position as the major buyers of advertising to the tech giants (of which there are only a few). In other words, the difficulties faced by the media industry weren’t a result of the emergence of the technology itself. Rather, they have been more a result of the digital age emerging within a radically neoliberal form of capitalism that tends toward monopoly power – i.e. a few large corporations dominating the market at the expense of smaller firms.

And this reality didn’t emerge out of the ether, but because of deliberate political choices. Choices such as shunning regulation, denying the existence of market failure, and refusing to challenge the market dominance of huge corporations – all of which resulted in large part from the aggressive lobbying of governments by big tech corporations themselves.

Is there a solution?

The Australian and French governments’ bold initiatives certainly represent an important first step in improving the situation. But a lasting solution will require much more radical action. Luckily, there are already proposals floating around.

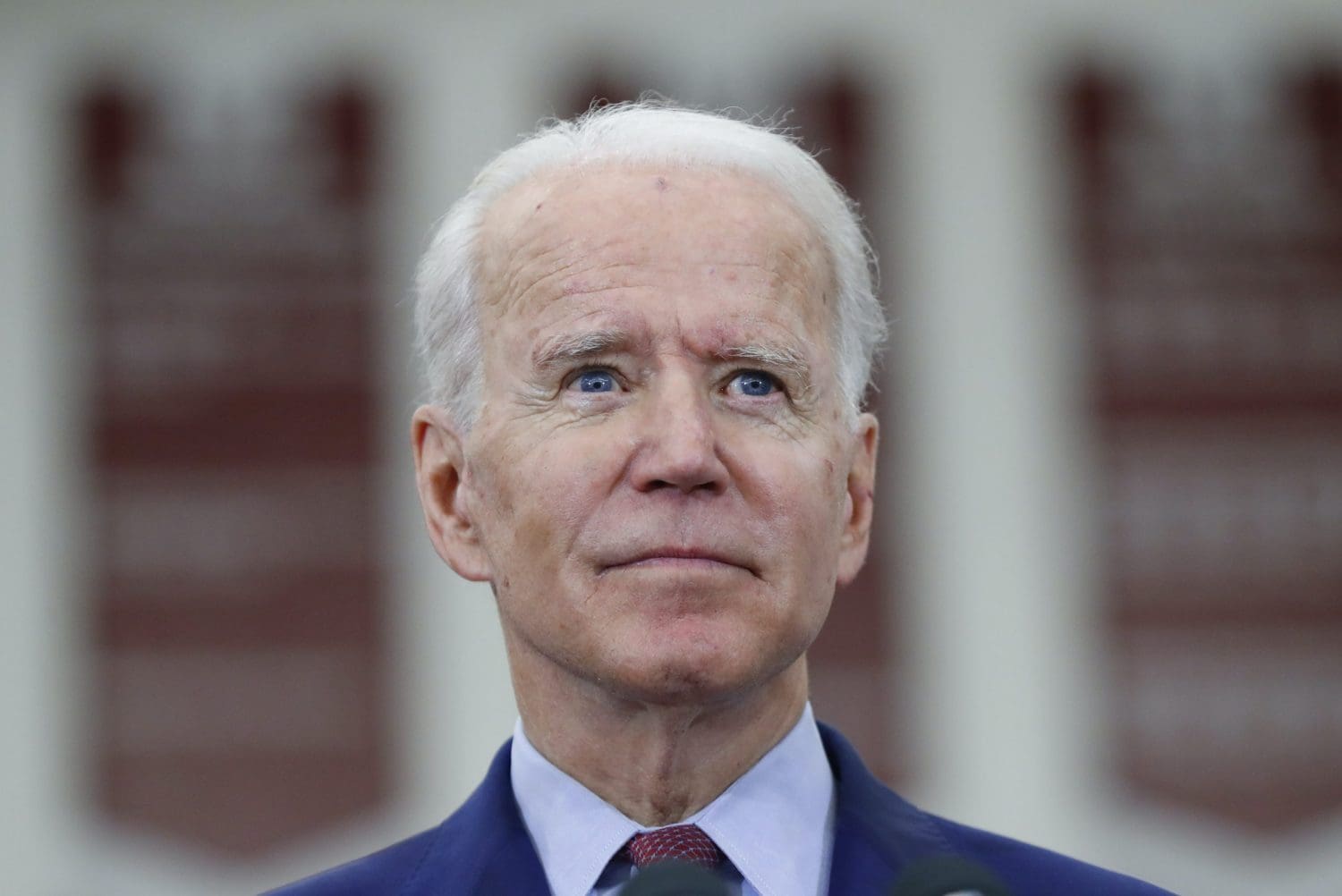

During the 2020 US Democratic Party primary election, for example, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren articulated blueprints for how major big tech companies might be broken up. Though neither of them eventually won the nomination, Sanders’ campaign in particular fundamentally influenced the debate and shifted the political center within the party. So much so that even the largely center-right figure Joe Biden, now the party’s presumptive nominee, has indicated that he’s ‘open to the idea’. And if it’s on the agenda even within one of the US’s two major parties, European governments have no excuse for not taking the lead.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons/DARPA