The Financial Times has published a new column but its author is former founding CEO of fallen private military security company Blackwater. And its content is a bid for services. Worse, his proposals would be yet another hugely misguided effort at controlling Europe’s refugee crisis.

A Prince among mercenaries

On Monday 2 January, an editorial [paywall] that read a little like a full-page advert in The Financial Times gave voice to Erik Prince, founder of the private military security company most commonly known as Blackwater. But also known as Xe, Academi and Frontier Services Group (though technically a different company, Prince is CEO). It changes its name after it encounters one PR balls up after the other. PR balls up or occasional felony that is.

If the name sounds a little familiar, it’s because in April 2015, a court of law found four Blackwater employees guilty of killing 14 civilians during the 2007 Nisour Square massacre in Iraq. More recently, Prince has been under investigation for money laundering. And family ties see him connected to Donald Trump as Prince’s sister, Betsy DeVos, enters Trump’s cabinet as Education Secretary.

The respected financial broadsheet allowed Prince to tout his services for what he believes is the answer to the ‘refugee crisis’ that has ‘overwhelmed’ European governments:

The public has lost patience with its leaders. If urgent action is not taken, the very existence of the EU is in danger. Based on many years’ experience in military and civilian business, I have a solution that will restore stability to Libya and mitigate the crisis.

A public-private partnership from hell

So Prince wants to stabilise the flow of migrants between Libya and Europe.

He rightly points out that hundreds of thousands of people have attempted to make that journey and that Libya’s unstable condition means it lacks the capacity to secure its own borders.

Prince proposes a public-private partnership through hiring companies, a little like Blackwater. An armed unit would help mentor Libyan border police in five patrol bases to cover smuggling routes with “agreed-upon rules of engagement and migrant detention and repatriation policy”. He proposes airborne surveillance, which one can assume means drones as well as search and rescue and “armed vehicle quick reaction forces”. The man sounds like he’s ready for war.

There would be nowhere for migrant smugglers to hide: they can be detected, detained and handled using a mixture of air and ground operations.

Prince believes this would cost less and be more effective than the EU’s current €35m-a-month operations.

What could go wrong?

He’s been doing it in Afghanistan, as he says, all this time. And no one has been fleeing Afghanistan.

Aside from Prince’s impeccable record at delivering uncontroversial privatised military services that have allowed him to evade criminal accountability for actions he presided over.

A signed affadavit has said that Prince “views himself as a Christian crusader tasked with eliminating Muslims and the Islamic faith from the globe”. That perhaps explains the rogue activities of Prince’s security outfit in Muslim countries. And potentially his interest in ridding Europe of refugees, many of whom come from countries where Islam is the dominant religion.

It also makes even clearer the self-serving nuance of his comment piece.

https://twitter.com/casperlabuscha3/status/811536700396728320

A little accuracy please

According to Prince, migrants travel unchecked to Libya, and they can then take a short (‘if dangerous’) trip to Europe.

It’s true. Europe lies a few hundred kilometres away from Africa’s northern coast. But smugglers do not intend for boats to go the whole way across. Boats only have enough petrol to land them away from the coast. They then have no choice but to take flimsy dinghies or swim the remaining distance, which makes more for a harrowing ordeal (if not an ocean grave).

A distress call is sometimes made so that the coastguards may rescue them. But contrary to Prince’s claim that the EU’s border security force is to save lives, the Italian government discontinued Italian search and rescue mission, Mare Nostrum. The EU replaced it with Triton, a Frontex operation whose aim was not to save lives but actually to secure the border. This in itself has been controversial, with little spirit for human rights.

Many migrants will also not make it all the way to Libya. On their journey, they face detention and torture by authorities. To escape, their only choice is to comply with the exploitative demands of traffickers. Others may be working in Libya or neighbouring countries and must flee the instability there themselves.

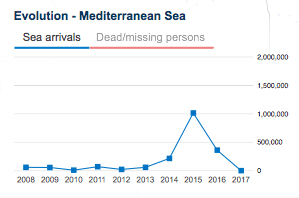

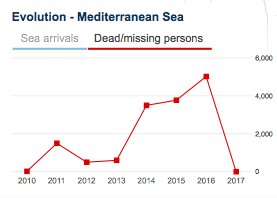

Prince believes that “more and more people think the journey is viable and are willing to take the risk”. But numbers have dwindled. The figures below from UNHCR show that fewer people are arriving by boat. In contrast, deaths by sea are increasing, some believe due to the greater risks smugglers are willing to take.

Prince also blames the “long, remote land borders” Libya shares with Algeria and Chad as a reason for smugglers’ access. But policing from European as well African officials has been unfruitful. Because corruption among border officials goes along way in facilitating smuggling activities in Libya. And Erik Prince may be stepping on those toes somewhat.

Less of this sort of thing

Prince’s proposal is flawed, frightening, and belongs only on the perplexing platform provided by The Financial Times.

His nod to aid and development in the region was more on the money. But migration flows and smuggling need a more sophisticated remedy than an unrelated and self-serving private industry. A private industry that has actually been managing Europe’s migration issues for some time. And with uninspiring results. Conditions in detention facilities, for example, have been deplorable – with allegations of abuse and exploitation.

The crisis does indeed need fresh thinking – but along the lines of making the demand for smugglers redundant. Trapping people in hostile conditions that make them pursue illegal means in the first place is not the solution. And neither is another private deal that places accountability in a black hole.

Get Involved!

– Read more articles on migration and mercenaries from The Canary.

– See more international articles at The Canary Global, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Featured image via Flickr/The U.S. Army