The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has often been the focus of prolific human rights abuses, and has been blamed for the spread of the ideology behind terrorist groups like al-Qaida and Daesh (Isis/Isil). So how is it that a supposed beacon of liberal democracy like the US enjoys such a strong alliance with a country many perceive to be the opposite of democracy? Medea Benjamin, the co-founder of activist group CODEPINK, exposes all in her forthcoming book Kingdom of the Unjust: Behind the US-Saudi Connection, available from OR Books.

The media narrative about Saudi Arabia has been particularly scathing over 2015 and 2016. Underlining this is its human rights record, that’s been condemned by human rights organisations, news pundits, and various states (including its allies). Despite this, it still enjoys strong cooperation from the same governments which are sometimes critical, and was even endorsed as chair for the UN Human Rights Council.

The US is one of these governments.

While Benjamin doesn’t reveal new sources exposing the connection, she curates the open source material to build a story that first shows how the kingdom represents ideals very different from those of the US, and then looks at why the aforementioned connection exists (and continues to be important and relevant for both sides). Below are just four key points from the book.

1) Wahhabism

She isn’t the first to point the finger at the ultra-conservative sect of Wahhabism (or Salafism), that advocates pushing the religion of Islam in a more puritanical direction. But this is an overwhelming part of the message in this book. And while there is plenty of debate to be had about the influences of Wahhabi-inspired extremism, the limited explanation included here is probably not enough to do the complex subject justice – especially as it is reliant on arguably biased source material.

2) Following the money

What is really interesting regarding the connection between Saudi Arabia and the perpetuation of terrorism is the financing of groups, and the source of the money originating from individuals within the kingdom.

Most significant on this front is the book’s focus on the Obama administration’s cover-up of revealing segments of the 9/11 report which allegedly expose the funding of the operation by elements within Saudi Arabia. The reason for this was almost certainly that the US did not want to upset its allies.

3) The real special relationship

The real pleasure of this book arrives at about Chapter 7, which is an enjoyable exposure of the US-Saudi union – its birth and growth.

From as far back as 1932, mutual interests started around the trade of oil and flourished among their opposition to the “godless communism” of the Soviet Union. This led to successive doctrines that ensured military aid and support between the two nations.

This is a relationship that hasn’t only been viewed with contempt from Western onlookers and human rights advocates. It’s also received the distinct displeasure of Wahhabi militants and certain Saudis, who disapprove of an alliance between a Muslim nation and an infidel nation.

But it’s an alliance that has remained strong throughout even the rocky elements of its relationship.

And why shouldn’t it? The gains are substantial as this quote from the White House press department highlights:

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the largest U.S. Foreign Military Sales customer, with active and open cases valued at aproximately $97 billion, as Saudi forces build capabilities across the full spectrum of regional challenges.

In other words, the US doesn’t just defer military obligations to the kingdom to take care of battles in its own neighbourhood. It also earns it a cool few billion.

But there is a cost. As Benjamin argues, such sales have the impact of not only destabilising the region but further undermining the national security of the US. And not only that. It also violates the UN Arms Trade Treaty, as Saudi Arabia has been accused of committing war crimes with the same weapons sold to them by the US (and the UK). Benjamin’s own advocacy group CODEPINK has been active in trying to stop these sales.

4) All sins are forgiven

The last chapter also provides fresh thought as it puts forward solutions – from soft change to structural reform, both of which are thought to have limited chance of occurring. Saudis have apparently resorted to protesting on the internet (through social media), risking the chance of punitive reproach, and Benjamin stresses the need to support fledgling movements that are challenging the norms in Saudi society.

And it’s not that the US is blind to the abuses or denies them. It lays out these same abuses in reports and in speeches every year. But it deals with the kingdom nonetheless, as if these problems were out of its hands.

Pointing to an interview Obama did with Jeffrey Goldberg, where the US President was highly critical of the kingdom, Benjamin notes:

How remarkable that the U.S. president, the most powerful man in the world, felt hemmed in by a Cold war-era alliance that no longer serves the interests of the United States, if it ever did.

Appropriately, she ends the book by challenging the assumptions that underpin that alliance.

Although clearly opposed to the current regime of Saudi Arabia, and the US alliance with that regime, Benjamin’s book sets out on an important mission to highlight the main concerns and human rights violations that Saudi Arabia is responsible for. And while analysis about more complex arguments could perhaps be stronger, the book’s real value lies when it talks specifically about the US-Saudi connection, which is why it is a truly enlightening read.

In short, it’s a relationship that doesn’t make sense, but at the same time makes so much sense.

Get Involved!

– Buy Medea Benjamin’s ‘Kingdom of the Unjust: Behind the US-Saudi Connection’ from OR Books.

– Read our other articles on Saudi Arabia.

– Support The Canary if you appreciate the work we do.

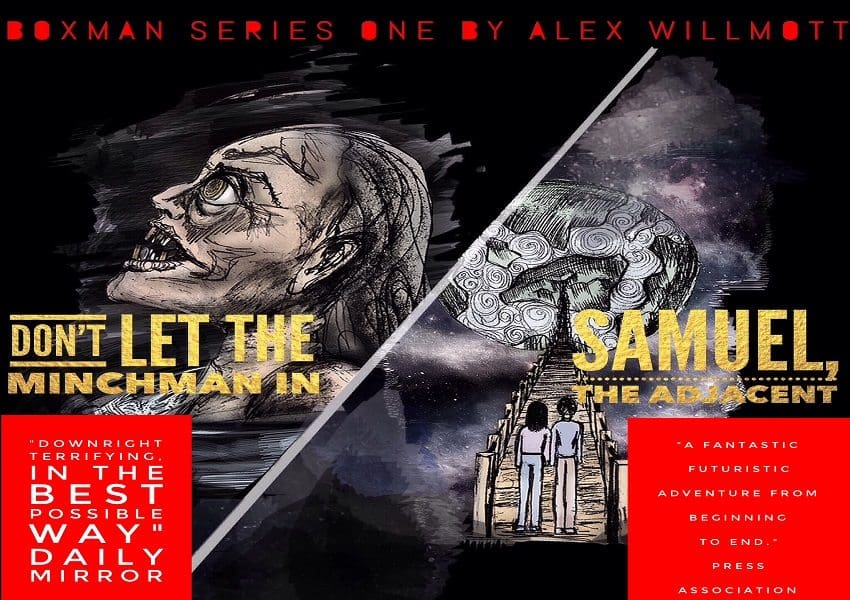

Featured image via OR Books