Kurdish communities in the Middle East have been at the forefront of the fight against Daesh (or ISIS) in the Middle East. Whether in Iraqi Kurdistan, where the corrupt nationalist government has received significant material and financial support from the West, or in Rojava, where the progressive and directly democratic administration has been blockaded by Western allies ever since 2012, the struggle of the Kurds will be key in defeating the Wahhabi extremists’ aim of carving out a puritanical state in the region.

In recent days, however, the West’s choice to support the mostly nationalist Kurds in northern Iraq has been opened up to criticism yet again. The rule of Masoud Barzanî, president of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) since 2005, expired at the end of August (after already being extended for two years by way of a special agreement), but the nationalist leader has once again fought to extend his term in office. According to his rivals, he is monopolising power in an illegal and unconstitutional way. The Goran (Change) Movement that Barzanî blamed for inciting protests, claimed a “coup against democracy” was taking place.

And now, Barzanî’s personal search for power (along with other factors) risks throwing Iraqi Kurdistan back into civil war. At the same time, stresses the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), these events could “severely undermine the campaign against Daesh”.

Having protested against corruption and nepotism in 2011, Kurds in northern Iraq in recent weeks once again took to the streets, with teachers, hospital workers and other public sector employees (who make up around 1.3 million of the region’s 5-million-strong workforce) going on strike. Their key demand was for the payment of wages that now stands over three months in arrears. The demonstrations also sought to push the ruling coalition into solving the ongoing presidency crisis.

According to the governing regime, the fight against Daesh and the drop in oil prices were the two main factors pushing the region to the verge of bankruptcy, but for one secondary school headmaster in the city of Sulaimaniyah, it was clear that political mismanagement was to blame. In addition to high levels of corruption and nepotism, the KRG had also raised tensions with Baghdad by building its own oil pipeline into Turkey – a move which led the Iraqi capital to cut its funding to the Kurdish north. In spite of the loss of revenue, though, many citizens logically asked where all of the money was going when a record 620,478 barrels of oil per day were exported independently by the KRG in September alone.

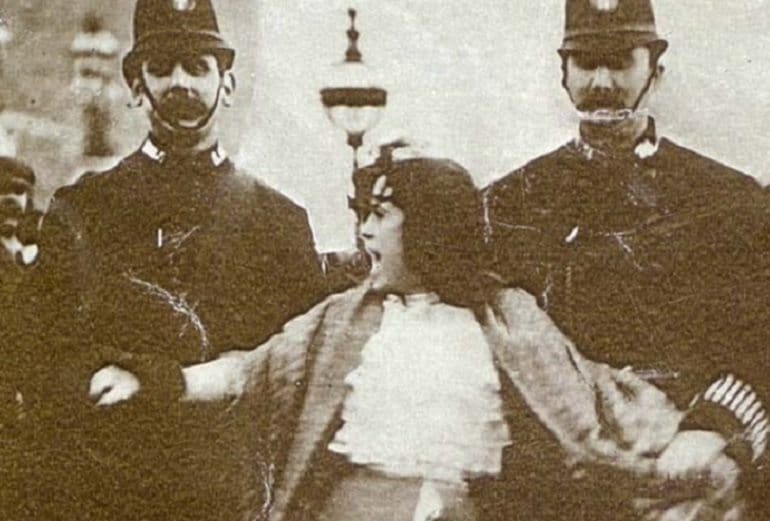

On October 8, talks resumed between the post-2013 coalition government partners of Barzanî’s KDP, the social democratic PUK and Gorran Movement, the Islamic Union (Kakgrtu), and the Islamic group (Komal) in an attempt to resolve the presidency crisis. Seventeen demonstrators outside the meeting, however, were attacked by riot police and, with deep political divisions flaring up, several people died in the following days.

One teacher who spoke to The Canary, on condition of anonymity, said he suspected Iran had a hand in the unrest, as Barzanî had previously stopped the region’s neighbour from using Kurdish army bases to support Assad’s war efforts in Syria. Another issue for Tehran, however, was that the Kurdish president had been stepping up his efforts for an independent Kurdistan in previous years, almost certainly encouraging Iranian Kurds to intensify their own fight for freedom.

In other words, it would not be entirely surprising if Iran wanted to get rid of Barzanî.

According to journalist Harem Karem, however, the main source of discontent was that the KDP had been acting in an incredibly undemocratic way regarding its coalition partners, “limiting the powers of non-KDP cabinet members by operating a KDP ‘shadow government’ within the government”. For example, Karem asserts, the chief of staff of Prime Minister Nêçîrvan Barzanî (Masoud’s nephew) had consistently appeared to have “direct instructions to intimidate and humiliate” non-KDP cabinet members.

At the same time, another education worker who spoke to us also suggested that Iran may be involved in the unrest, but insisted that the main reason for the protests was that citizens were simply fed up of all the injustice and economic difficulties they were facing. Speaking anonymously through fear of persecution, he argued that Turkey had almost certainly been playing a role in the escalating conflict as well. The MİT (the Turkish intelligence agency), he stressed, had a record of interfering, having armed both sides in the Kurdish Civil War (between the KDP and PUK) in the 1990s.

Peaceful political dialogue, the source insisted, was just not as commonplace in Iraqi Kurdistan as in Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan), as many Iraqi Kurds would “die for the party they supported whether it was wrong or not”. And, while citizens were sick of the extended Barzanî family using Masoud’s powerful position to line their own pockets, he said, protesters’ attacks on KDP offices seemed to ignore the errors of the other parties also participating in the coalition regime.

The source asserted that President Barzanî was indeed taking advantage of the anti-Daesh war efforts to scare people into supporting his continued rule, in spite of the fact that there was clearly “enough safety for elections” to take place. With US politicians such as Joe Biden allegedly having promised the KDP leader behind the scenes that there would be “a Kurdish state in our lifetime”, the source suggested that Barzanî simply wanted to stick around in power long enough to take credit for the Kurdish independence he and his family had advocated for so many decades.

It is undisputable that supporting Kurds and stopping Turkey’s anti-Kurdish war are indeed the only way to defeat Isis. The main question, however, is which Kurdish forces are the biggest supporters of democratisation? Barzanî’s KDPs track record does not make for good reading at all. While the forces for greater democracy in Iraqi Kurdistan should be supported, then, it is clearer now than ever before that officially recognising the democratic cantons of Rojava is the best way forward. Not only does it make the most sense to equip the incredibly effective Rojavan defence forces with all they need to bolster their fight against Daesh, but supporting the courageous egalitarian experience they defend is quite simply the right thing to do.

Featured image via US Department of State/Flickr