The peace process in Turkey did not collapse. It was destroyed by its president’s ego.

Turkey’s dominant political ideology

‘Egotism’ is the current Turkish president. It is also the current ruling party. But this June, ‘Cooperation’ won seats in parliament, taking the government’s majority away in the process. The latter, though, as the home of ethnic, religious and sexual chauvinism, could not allow this situation to continue unchecked.

Since taking power in 2002, the ruling AKP has blended neoliberalism, Islamism, and nationalism to create a toxic political potion. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has led the party to successive electoral victories ever since he became prime minister in 2003 (he has been the country’s president since 2014).

After the Arab Spring began, however, Erdoğan’s attempts to portray his party’s mixture of discriminatory ideologies as the way forward for the region began to unravel. With Saudi and Qatari money pouring into Syria (with Western complicity) and placing Wahhabism at the forefront of the struggle against the Assad regime (and fuelling the growth of Daesh and Al Nusra respectively), Turkey’s hopes of installing a government in Damascus in its own mould looked destined to fail.

Erdoğan’s flip-flopping on ‘the Kurdish Question’

Nonetheless, when the Rojava Revolution in mid-2012 saw equality and self-government placed at the top of the agenda in the Syrian Kurdish regions on the Turkish border, Ankara decided that it was better to have Wahhabi extremists on its border than progressive Kurds. Along with its corrupt allies in the KRG, Turkey immediately blockaded the autonomous Kurdish communities in northern Syria, and was even accused of supporting Daesh.

At the same time, the AKP began to suspect that the ‘Kurdish Question’ should at least appear to be higher on its ‘to do list’ if it were to win sufficient electoral support in upcoming elections and encourage Turkish Kurds not to support the revolutionary experiment in Rojava. As a result, it finally answered the calls of the left-wing guerrillas of the PKK for peace negotiations at the end of 2012. In reality, though, it showed little commitment and refused to take sufficient steps to ensure peace, continuing to build new military outposts in Kurdish communities.

The final straw, however, was when Daesh intensified its assault on the border town of Kobanî in mid-September 2014. The Turkish embargo on the city was maintained, and Turkish tanks simply watched from the other side of the national boundary as the Wahhabi extremists gradually advanced. At the same time, reporters were attacked by Turkish police, who continued their attempts to stop activists from crossing the border to support the resistance of progressive militias in Kobanî. And this repression culminated in October, when dozens of protesters were killed by the police.

In spite of the increasing tensions, the PKK maintained its commitment to the peace process, while criticising Ankara for ‘being more ready to negotiate with IS than Kurds”. Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç, though, would soon say ‘from now on, we may refrain from speaking about the resolution process’ to which ‘we are not obliged’.

The final straw

Essentially, Kobanî was the undoing of the Turkish peace process, as it showed Ankara’s stubborn hostility to any progressive experience that challenged its own divisive rhetoric. Soner Cagaptay, director of the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute, however, emphasises that the political dynamics in Turkey really changed during the elections of June 2015, when the Peoples’ Democratic Party (or HDP) managed to gain the support of both left-wingers and conservative Kurds (who were simply disappointed with the government’s stance on the Daesh siege of Kobanî). Turkish Kurds, he says, now had ‘political consolidation’, and were no longer susceptible to the fear-mongering oratory of the state regarding the PKK.

The fuse was definitively lit, though, when Daesh undertook a massacre in Suruç (the town lying on the other side of the border from Kobanî) on 20 July, killing members of the Socialist Federation of Youth Associations (SGDF) who were on the way to help rebuild Kobanî. In fact, a government whistleblower suggested a week later that the attack had been ‘designed by Turkish officials’.

After the Suruç Massacre, everything spiralled out of control. For many Kurds in Turkey, it was the final straw. They could no longer trust the state to protect them, and organised their own forces to defend themselves. In response, Ankara launched a crackdown on ‘terrorism’, in which over 800 of around a thousand arrested in the first week were ‘alleged PKK members’ (i.e. people who had played no role in the events of Suruç). The AKP, having failed to gain a majority in the previous month’s elections, was very clearly exploiting the existing tensions in the country to end the peace process and launch a war against the progressive Kurdish movement in the country.

A return to war

As the Turkish State finally promised the USA that it would participate in the war against Daesh, it almost immediately launched airstrikes against PKK positions in the Qandil Mountains of northern Iraq. For journalist Patrick Cockburn, this would be ‘America’s worst error in the Middle East since the Iraq War’. While Joris Leverink, an Istanbul-based journalist, asserted that US complicity with Turkey’s attacks on the PKK would be a clear sign of the superpower’s ‘disregard for Kurds’.

In other words, the ‘gender equal Kurdish guerrilla fighters‘ of the PKK and its progressive allies in Syria (who had been the ‘most effective forces in the battle against IS both in Iraq and in Syria’ and had long sought peace with the Turkish State) were now under heavy bombardment from the Turkish army. The state media, meanwhile, consistently referred to the PKK as ‘terrorists‘, while outlets linked to the Turkish regime would talk about soldiers being ‘martyred‘ and how the PKK had ‘exploited’ the peace process.

In recent days, Ankara has claimed that more than 2,000 guerrillas have been ‘neutralised’, while insisting it is ‘taking precautions’ for the re-election called for 1 November, by mobilising ‘385,000 security forces, including 255,000 policemen and 130,000 ground forces’. In short, there would almost certainly be very little freedom for those opposed to the AKP in the run-up to the elections.

Rising authoritarianism

The simple fact is that Turkey is suffering from rising fascism, a continuation of the tradition of state violence, and repression of the media. At the same time, Kurds who did not belong to the PKK before Ankara’s offensive are now considering joining the group. One student, for instance, told the BBC he ‘did not want to use guns’, and that people were simply reacting to what they considered to be ‘Erdogan’s war’.

To put the situation into context, ‘security forces’ of the Turkish State have killed many more civilians than the PKK (which, to my knowledge, has been accused of killing just one), murdering at least 21 (including a 35-day-old baby) in Cizre at the start of September and eight (including a child) on 1 August during its attack on the Iraqi village of Zergele.

Turkey’s political elites failed to win sufficient support for their ideas in a non-violent manner, and thus resorted to violence. And, while I don’t agree with using the term ‘terrorism’ (which erroneously makes politics seem ‘black and white’), my investigations have led me to believe that, if any group deserves to be called a terrorist organisation in Turkey today, it is the Turkish State itself.

Kemal Kirişci, the Director of the Turkey Project at the at the Brookings Institution, says President Erdoğan has sought to ‘rally nationalist and conservative votes to AKP’ with his war against the PKK, and to weaken the HDP by suggesting it is the same as the PKK. In Kirişci’s opinion, though, Turkey is ‘destined for more instability … unless Erdoğan reconsiders his strategy’. Soner Cagaptay, meanwhile, insists that ‘Erdogan has polarized his country’, and that it is ‘ultimately up to him to tamp down tensions before they explode’.

Both Kirişci and Cagaptay are right. Erdoğan and the chauvinist AKP are the primary culprits for Turkey’s current descent into civil war, and are therefore the only ones who can stop it. The PKK, meanwhile, has only killed Turkish soldiers and policemen because Ankara launched a military campaign against it, and remains committed to the search for peace both in Turkey and in the wider Middle East.

The Turkish peace process did not collapse, as the mainstream media often likes to suggest. Instead, it was destroyed by Erdoğan’s hunger for power.

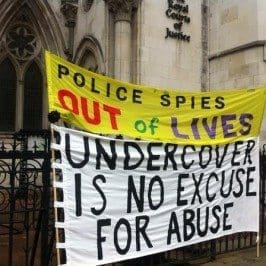

Featured image via Wilson Dias