The Canary is currently in Venezuela. This is the latest in our series of on-the-ground articles.

While we regularly see images of Venezuelans searching through garbage in the corporate media, we rarely see coverage of the people distributing vital food packages to millions across the country. The Canary spoke with one of Venezuela’s Local Provisioning and Production Committees (CLAPs), that are helping to supply government-subsidised food to over half the population.

CLAPs

Yoraima Youine is a local organiser in the La Brisa district of Caracas, Venezuela’s capital city. The Canary asked Youine about how the CLAP system works:

Each CLAP has its own geographic region – this specific CLAP’s name is Rosario de los Pirineos. We’re currently feeding 333 separate families, but we’re just one of hundreds of CLAPs across Caracas. Various people from across the community – not just from one particular social organisation – organise the distribution. Here, for instance, we have an organisatory body of 15 people. Government workers bring the food here, and volunteers distribute it based on local censuses.

With the economic situation here, the CLAP allows Venezuelans to access basic, affordable food, while not having to worry about currency fluctuations and speculation.

There’s a lot of coverage of a ‘food crisis’ in Venezuela. The Canary asked if CLAPs are a direct response to this, or part a solution to wider issues of food insecurity?

No, there’s no food crisis. Here you can get the food – the problem is the price. That’s why the CLAPs exist: every Venezuelan has a constitutional right to food. People in regions that don’t yet receive CLAP, moreover, can receive it through their local institutions.

Many Venezuelans have also spoken about ‘bachaqueros‘: people who have power over the country’s food supply, and abuse it by hoarding key foodstuffs to inflate prices.

The boxes seemed fairly large. Youine spoke about how many people they feed, for how long, and with what:

Well, a ‘family’ is defined as up to 6 people within a given household. They can collect a box once every 15 days. Each box has 19 different food items and costs around 500 Bolívars [roughly US$0.20].

The Canary saw the contents of the boxes, which include spaghetti, beans, lentils, and corn flour (essential for making arepas, a staple across much of Latin America). A separate food package supplies perishable protein sources such as chicken and beef. Residents added that, in December, boxes came with extra protein and small games for Venezuelan children.

Sense of community

There’s no lack of a sense of community around Caracas, and food collection day was no different. Residents shared numbers and planned weekend activities. “Everything moves in conjunction”, said Julio Palacios, a local drum teacher planning a ‘rumba’ (dance) on Saturday evening.

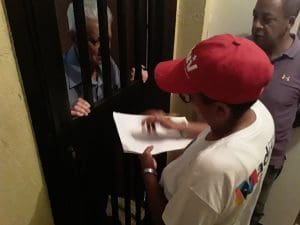

The organisation, moreover, doesn’t stop at the point of delivery of CLAPs. The Canary joined some volunteers conducting the census for food distribution through some of the capital’s high rising apartment blocks.

The scale of Venezuela’s food distribution project is absolutely immense, and altogether more impressive given its massive volunteer base. If not for the CLAPs, the type of ‘humanitarian crisis’ narrative the corporate media promotes so enthusiastically might well be reality.

Venezuela’s economy is ‘screaming‘, and the noose around its neck is tightening. As imperial powers strip the country of more funds and resources, the Venezuelan government’s ability to subsidise food programmes will fall. What seems unconquerable, however, is the energy and solidarity of the country’s popular classes to ride this storm out together.

Featured image via John McEvoy