On 8 February, the Guardian published an article entitled “Emmanuel Macron, pilloried at home and abroad, is Europe’s best hope”. If one message could unite France’s Yellow Vest movement, which began in November 2018 in response to a hike in fuel taxes, it’s that this is total nonsense.

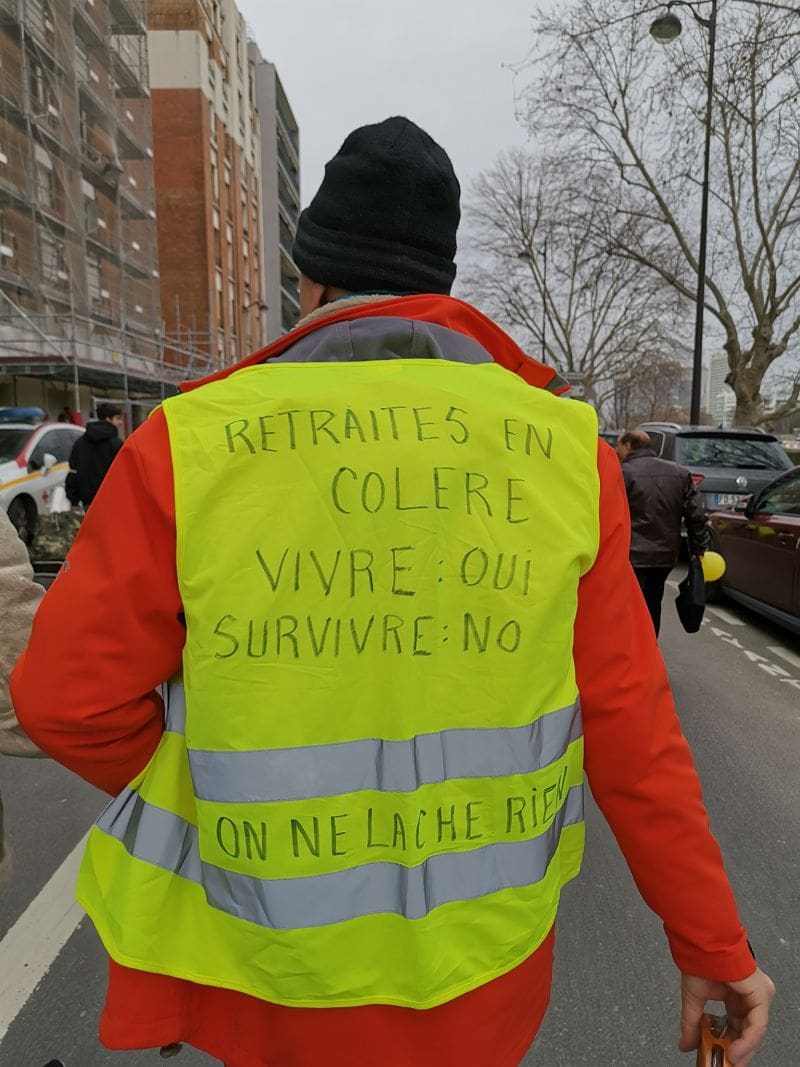

The Canary was on the streets of Paris with the Gilets Jaunes (Yellow Vests) as it entered its 67th straight week of mobilisation – France’s longest-running protest movement since the Second World War.

Who are the Gilets Jaunes?

The Gilets Jaunes have no clear leadership, demands, nor strategy – aside from taking to the streets each Saturday as an expression of popular, rather than representative, democracy. The movement appears to be principally an insurrection against; what it is actually for is a constantly changing battleground.

“We’re revolting against the system… We’re people who are disappointed and disgusted by the political system, especially the different parties. We want to say stop to what’s happening – stop to inequality, stop to injustice, stop to police violence… This is no longer a democracy”, claimed an activist as the Yellow Vests marched along the River Seine.

“For me, it’s the spiritual continuation of the Paris Commune“, claimed an older activist carrying a flag to commemorate the Spanish Civil War.

“Gilets Jaunes have restored a sense of community that I felt had been lost in France”, added another. His friend, an orthodox priest, nodded along sympathetically.

Since the Gilets Jaunes have no official leadership, it’s vulnerable to being commandeered by pragmatists. And given the movement makes no consistent demands, there’s nothing that necessarily conditions its termination. “What would have to happen for Gilets Jaunes to end?”, I asked one activist. Her first response was to laugh.

The mass media

On 22 February, the Gilets Jaunes marched to the headquarters of the French mass media – TF1, France Télévision, Radio France and C8 – imploring them to “tell the truth” about the significance of their movement; about Macron’s punishing pension reforms; and about the government’s authoritarianism.

Aziz, a representative of the construction union BTP, spoke passionately about the French media:

The role of the media is to try to divide the movement by showing that the Yellow Vests are the violent ones. Yet even the videos that they broadcast on certain channels, we see that the violence isn’t coming from the people… We see the way that they’re repressing us, this is no longer a democracy.

The international media has been just as bad, they complained.

Macron responds, Macron disappoints

Macron spent the morning of 22 February in Paris’ International Agricultural Centre, where he was angrily confronted by Eric Drouet – arguably the second-ever Gilets Jaunes protester.

Drouet was quickly dragged out of the building, but a visibly exasperated member of the public cornered Macron shortly after.

“The people are in the streets”, she told Macron. “There aren’t that many people”, he responded.

“Come to the streets and see for yourself”, she said, to which he replied: “Unfortunately I have too much work to come out to the streets”.

“Me too”, she retorted, “I work six days a week”.

Common denominator

If something unites the Gilets Jaunes, it’s a profound disdain for Macron and the political class he represents. Asked to describe Macron in one word, a Gilets Jaunes activist responded bluntly: “Pawn”.

Not only has Macron met the Gilets Jaunes movement with condescension, but also with severe violence: 35 people have been blinded; five people have lost hands “torn off by explosive grenades”; 318 protesters have suffered “severe head injuries”; and “6,000 persons in total have been injured”.

There have also been three deaths: “an old lady targeted at her window by a grenade; a young man pushed into the Loire River and not saved from drowning by the police forces in attendance, who themselves have hidden the fact for weeks; and a man pinned to the ground, whose larynx was broken and died by suffocation during an identity check”.

Centrism’s graveyard

If France’s 2022 general election is another run-off between Macron and far-right Marine Le Pen, it isn’t clear how many French voters will once again hold their nose and elect Macron, a president widely equated with the rot of corporate influence and corruption. In 2018, French pollster Ifop reported its highest ever recorded disapproval rating for Macron: 73%.

The polls, meanwhile, suggest that the French left is divided, and little closer to power than in 2017.

In the graveyard of European centrism, the xenophobic right thus continues to gain ground. Macron’s recent attempt to pander to this populist rightward trend may have won him a few more supporters, but it has dragged the political debate farther into the gutter.

If the French far-right manages to position itself as the antithesis of a hated establishment (as it has done with success in the UK and the US), France may be the next in line to elect a racist, nationalist government.

There is widespread anger here – clearly manifested within the Gilets Jaunes movement – that the French left could capitalise on. In March, Macron will face his first major political challenge in France’s municipal elections. And according to some estimations, the left is beginning to show some “signs of unity – feeding hopes they can turn social revolt into a challenge for the presidency itself”. The French unions, moreover, still retain some of their historic stopping power.

Yet in the present scenario, the words of Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci seem darkly fitting:

The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.

Featured image via author