CORRECTION: The headline was changed for clarity from “In an exclusive interview former Ecuadorian foreign minister explains how lawfare has ‘blurred the collective memory of the people'” to “In an exclusive interview former Ecuadorian foreign minister explains how lawfare is an attempt to ‘blur the collective memory of the people'” at 8.20pm on 17 September.

This is part 1 of a 3-part interview with Guillaume Long, the former foreign minister of Ecuador. Part 2 covers systemic global corruption, and part 3 covers Ecuador’s decision to grant political asylum to Julian Assange. The interview has been edited in part for clarity.

On 14 September, former Ecuadorian foreign minister Guillaume Long spoke exclusively with The Canary about the role of lawfare (the weaponisation of the legal system against political opponents) in the retreat of left-wing governments across Latin America.

The pink tide

After the election of Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez in 1998, a wave of progressive governments swept across Latin America. By the mid-2000s, the so-called ‘pink tide’ had brought left-wing parties into power in Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Ecuador, and Bolivia – covering some three-quarters of South America’s population.

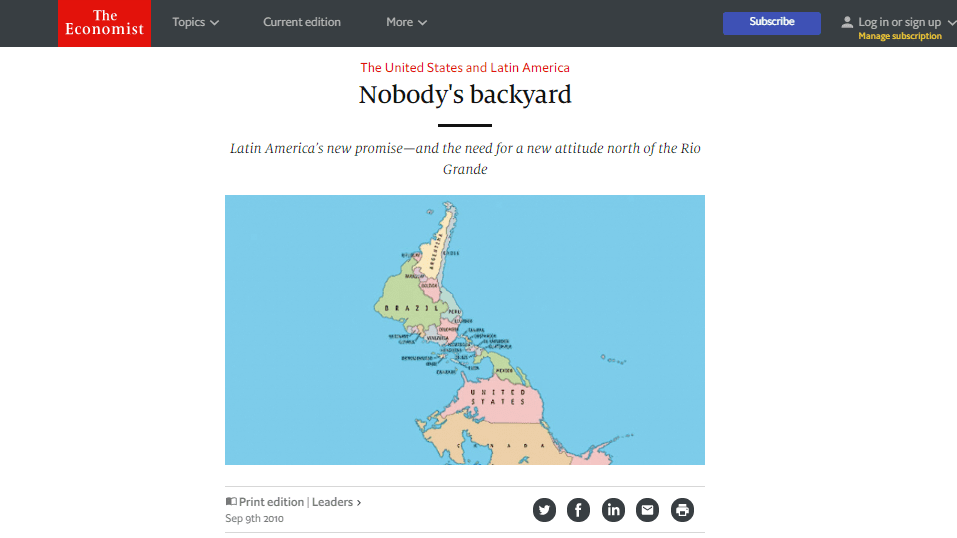

This profound transformation didn’t go unnoticed. In 2010, the Economist issued a piece entitled Nobody’s backyard, with an inverted map of the Americas showing Latin America looking down upon the US. As the pink tide governments formed regional blocks to challenge US influence in the region, it looked as if the Monroe doctrine might be consigned to history. Was Washington’s run of treating Latin America as its ‘backyard’ no more?

Two decades after the historic inauguration of Chávez, however, the pink tide has largely washed away. There are numerous reasons for this: tides, by nature, cannot stay in forever. Constituents tire of the same names and faces, regardless of the legacy they leave.

The pink tide also came at a critical moment. A commodities boom – increasing the global prices of materials like oil and metals – meant resource-rich nations could invest in popular social programmes, lifting millions out of poverty. But when the boom abruptly ended in 2012, the governments still dependent on exporting raw materials were hit hardest.

Lawfare

There is also a more sinister explanation for the retreat of the pink tide: the practice of lawfare. Unlike the brute force of military intervention, lawfare topples governments through political judicial assaults. In other words, politically-charged investigations are used to construct legal barriers to the normal functioning of democracy.

The Canary spoke with Guillaume Long about the pink tide, and the role of lawfare in its retreat. As Ecuadorian foreign minister under left-wing president Rafael Correa (2007-2017), who is widely understood to be a key victim of lawfare, Long is well-placed to discuss Latin America’s turn to the right.

Has lawfare been the key element in rolling back the pink tide in Latin America?

The factors for the decline of the pink tide are multiple, and obviously every country has a different case scenario. In some cases, there were democratic factors. But it’s important to say that in other cases, the pink tide was eroded through non-democratic means. I would argue that one of these cases was Brazil, where you had a completely illegitimate impeachment process against Dilma Roussef, which started with corruption allegations.

They couldn’t find anything and still wanted to impeach her so they just went for a change of budget accusation – it’s unbelievable and to this day they’re still looking and still they can’t find anything – and Dilma is extremely honest, and they’re never going to find anything. That was the first thing: to get a right-wing government in, and then they organised elections and they barred [Luiz Inácio] Lula [da Silva] from running for the 2018 election on bogus charges. And that is a clear case where lawfare played a major role in preventing leftist or left-of-centre governments coming to government: it’s clear that Lula would have won easily – and this was prevented through lawfare.

You’ve got a similar process that’s been taking place in Argentina. It’s been less successful than in Brazil – so what I think is very likely to happen in Argentina is a left-of-centre government elected with Alberto Fernández as president and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner [no relation] as vice-president.

Is lawfare so effective because it’s not only been used to block political campaigns, but also tarnish the legacy and memory of popular leftist movements? Does this apply to Ecuador?

You’ve got a very important case of lawfare in Ecuador. It’s similar to Brazil, except that instead of being in prison, Correa is in exile. But in this case, it’s for a pre-trial detention – it’s not even a prison sentence.

The purpose here is preventing him from being in Ecuador, participating in Ecuadorian politics, in a democratic political debate. It’s about making sure that he’s out of the game, and making sure he’s not on national soil. It’s remarkable because even Interpol, which isn’t exactly a leftist radical organisation, rejected the red alert and Correa can pretty much go anywhere in the world. But he cannot go to Ecuador because he would be arrested and imprisoned. And it’s not just Correa, it’s a number of former ministers from his cabinet…

I think that there has been a nefarious role played by the media – just as the judiciary has played a role in terms of making sure that people are intimidated…

The role of the media is to cover up these abuses and at the same time create a narrative that focuses on corruption – but it also tries to blur the collective memory of people, and of these historic processes. In the case of Ecuador, it’s amazing – it’s almost like there’s a self-censorship of the media. They won’t use the word Correa, or they won’t use the words Citizens’ Revolution to see if they can banish it from history. [Emphasis added].

Authoritarianism in new clothes

Long continued by discussing how authoritarianism has been re-packaged in the form of lawfare:

I think lawfare is the new way in which authoritarianism is expressed. So you’re not seeing the authoritarianism of the 1960s and 1970s through military government, torture, political assassinations and so on and so forth. You’re seeing a new sophisticated form of authoritarianism – but it’s still authoritarianism, it’s essentially taking away judicial independence.

I don’t know if it’s more sinister [than past military coups in Latin America] – because killing and torturing people is pretty sinister; so far lawfare has claimed less lives. But I think it’s more sinister in the sense that it’s more difficult to pinpoint, to identify, and easier camouflaged if you don’t have an honest media. The problem in Latin America is that, by and large – of course there are lots of exceptions… – there’s a media that is essentially in the hands of the corporate elites; a media that didn’t like what the pink tide was doing, because it was taking some power away. Not even some wealth away, but it was sort of changing the power and wealth dynamics: the redistribution of wealth dynamics in society. And the media is seeking revenge on these governments…

So the problem with that kind of lawfare is if you don’t have the media explaining the ins and outs of so-called corruption cases and bogus accusations – exerting some kind of checks and balances – it’s more sinister because it’s more difficult for people to understand.

Some have argued that the US is behind the use of lawfare in Latin America. What do you think the role of the US has been in this process, and what does this suggest about the US-Latin American power dynamic?

On the role of the US, obviously it’s very difficult: we don’t have all the access to the information. But yes, I suspect the US has played an important role. We already have some evidence that it has. There are some leaks about a very famous meeting in Atlanta in 2014 where some of this judicialisation of politics – lawfare – was probably planned in a way that was relevant for Latin America.

And we can see how warm and friendly the US has been with the governments that have carried out this kind of lawfare. In the case of Ecuador, there were high-profile visits by Mike Pence, Mike Pompeo; at the beginning Paul Manafort visited.

And there’s a very clear geopolitical realignment. If you look at the result of lawfare in Ecuador and this government’s actions in terms of its foreign policies… You see Ecuador’s position towards Venezuela: it’s a 180-degree turn… and now Ecuador’s given access [to the US military] to an area in the Galapagos islands.

And who are the winners? The US corporations. They’re back where the TransLatinas [Latin American transnational corporations] were. In fact, they’re buying privatised TransLatinas. Think of Embraer, which was the pride of Brazilian industry. This aeronautics company was selling a lot of its aeroplanes to Europe – it was third in the world after Boeing and Airbus. It’s just been privatised to Boeing for peanuts – for absolutely nothing. Part of the reason that it was privatised at such a low price was because corruption has eroded the company’s image. The corruption allegations – I would say the instrumentalisation of corruption – has eroded the image of these corporations, and they’ve been sold for nothing.

Disguise wearing thin

Since the Intercept began publishing a trove of leaked documents relating to the Lava Jato corruption probe in Brazil, the disguise of lawfare as a democratically viable process has worn thin. And alongside the gradual disintegration of lawfare’s legitimacy as a political weapon, Latin America’s move to the right is weakening. “I really think that if you look at the right-wing governments in power in [Latin America] at the moment”, explained Long, “they have low levels of legitimacy, often weak coalitions…. I think that the right-wing cycle will be short if it’s democratic. If it’s authoritarian, it could be extended for a little longer.” He continued:

It’s not the equivalent of a mirror image of when pink tide governments had 60, 70, 80 percent approval ratings with very charismatic leaders. These governments retain a lot of legitimacy because of their social and economic policies, and because of defending the sovereignty of these countries in the context of traditional great power meddling and imperialism.

And hope, it seems, is already on the horizon in Argentina.

Featured image via Wikimedia – Cancilleria de Ecuador